Why no productivity hack will solve your overwhelm

How the Internal Family Systems model can help you listen to your inner wisdom and get unstuck

👋 Hey, I’m Lenny, and welcome to a 🔒 subscriber-only edition 🔒 of my weekly newsletter. Each week I tackle reader questions about building product, driving growth, and accelerating your career. For more: Lenny and Friends Summit | Hire your next product leader | My favorite Maven courses | Lennybot | Podcast | Swag

When I was working on a post about productivity tactics (which went on to become one of my all-time most popular), I shared a draft with my Newsletter Fellow Natalie Rothfels. She is a former product leader and now a full-time exec coach, and I had a feeling she’d have thoughts. Boy did she:

“When people come to me with productivity questions, they can often recite many of the tactics you articulate, but they’re still unproductive, primarily because they are people-pleasing and have poor internal awareness of how much they can physically get done. It sends them into emotional overwhelm, which then sends them into internal shaming, which then is a huge, huge, huge blocker to any productivity.”

I knew I needed to hear more. This post is Natalie’s answer to anyone who’s struggling to keep their head above water at work. It’s one of the most powerful posts I’ve published, and I truly encourage you to create space to read it.

Natalie is an executive coach who works with co-founders and executive teams, helping them build interpersonal skills to become more effective leaders. She spent a decade as a product manager building educational tools at Quizlet and Khan Academy and now helps leaders build their emotional intelligence, influence, relationships, and ability to navigate conflict. She is a certified Internal Family Systems practitioner and a facilitator for Stanford Graduate School of Business’s Interpersonal Dynamics course, aka “Touchy Feely.” She also recently launched The Ripple Deck, a facilitation tool for building connection. You can follow her on LinkedIn and X.

My coaching clients usually come to me feeling stuck, burnt-out, and looking for productivity tricks. They are trying to strong-arm their way through overwhelm and exhaustion using coping mechanisms and tactics that were once effective but no longer are. So they bring their desperation to me, hoping for another framework for time management.

But looking outside themselves to solve their overwhelm is a trap. Inner conflict is the major hidden driver of productivity and burnout issues at work—and the most common issue for the leaders I see. These folks are at a developmental edge.

To get to the next level externally, they have to start by looking inside.

As you turn your attention inward, you won’t find a singular you but instead many different parts that make up who you are. Some parts help you manage your time, and other parts help you lose track of time entirely; some think analytically, and others work intuitively and non-linearly; some strive for individual excellence, and others prioritize collaboration with your colleagues; some feel competent and confident, and others criticize you and tell you you’re not enough.

When these parts are especially loud or in conflict with each other, this is a predominant reason you find yourself stuck, procrastinating, overwhelmed, or burnt-out.

This was exactly the case for Gustavo, a Director of Product who came to me saying, “I’m dropping balls left and right. I need help with time management and prioritization.” He could rattle off every productivity tool and how he was using them, but he was still ineffective at getting through his big weekly tasks.

As we dug deeper, it became clear that one part of him (the same part that brought the topic to the coaching session) wanted better time management skills. But another part of him couldn’t fathom disappointing anyone and was busy building up an infinite, never-ending list of work by constantly saying yes. A third part of him was so ashamed of and exhausted by the constant battle between these two other parts that it was nudging Gustavo to give up on the job entirely and quit.

Coaching Gustavo to prioritize one big thing each day or turn on DND mode at work did not solve his stuckness, because the core issue was not time management. It was an internal conflict that’s unsolvable by external productivity tools.

What did work was helping him uncover and address his seemingly irreconcilable feelings, needs, and fears—the voices of his many different parts that were wreaking havoc on his productivity and mental health.

If you relate to Gustavo, please know that it doesn’t have to be this way.

Internal Family Systems (IFS) is a powerful method for uncovering and relating to different parts of ourselves (especially the ones in conflict with each other) and developing a more integrated, aligned, and collaborative self. Though developed in the context of personal therapy, it is a highly effective tool for navigating the workplace, too.

Taking on a new project, negotiating your salary, handling a new promotion, delivering constructive feedback—these topics all tend to trigger inner conflict for most of us. IFS can help us turn toward that tension constructively so we can build the clarity and courage required for the next evolution of our professional development.

That’s how it worked for Gustavo, who said: “I realized that it’s not about time management. The thing I’m actually working on is building my own tolerance of chaos at work. It’s about feeling less out of control and recognizing when I’m spiraling into unnecessary anxiety, so I can work with and comfort those parts of me. I think I was actually causing more chaos for myself and my team by sort of pretending that things weren’t chaotic and trying to keep it all together. Now I’m more focused on recognizing the chaos without it totally taking over the rest of my day.”

In this piece, I’ll guide you through the same process I used with Gustavo to identify your parts and navigate the inner conflict that leaves you overwhelmed. You’ll learn how to notice and listen more effectively to the competing voices within you and then facilitate a more effective dialogue between different parts of you so you can break through stuckness, get on with your day, and learn to care for (rather than bully) yourself more in the process.

A brief primer on Internal Family Systems

Imagine you’re driving a bus. But it’s not just you in the vehicle—the bus is filled with different parts of yourself, each with its own perspective, needs, and fears. Some are shouting directions, others are arguing about the route, one is perfectly relaxed and chilled out, and a few are observing from the back, scared the chaos is never going to end. Frequently, one part runs up to grab the wheel and steer you in an unexpected direction. Soon, another part follows and shifts your course again.

This is the first key principle I want to highlight from the IFS model: we all have many parts. We are not just one monolithic self that’s the same in every context or has a fixed personality.

If you listen to all the parts on the bus at once, it can sound like total mayhem and chaos. But when we take time to be with and listen to each part, one by one, we learn a second key principle of IFS: all parts have positive intentions, hope, and wisdom for us (including the parts that like to procrastinate or criticize us!).

Let’s bring this to life with a personal example. As I sit down to draft this article, I’m aware of a variety of different parts on my bus.

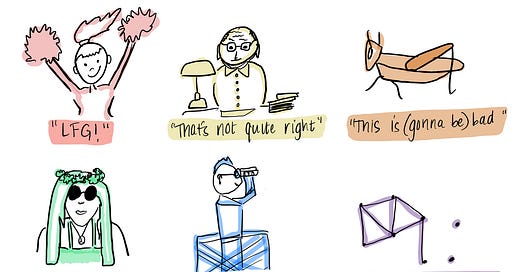

One part is hopeful and excited. She takes the form of an inner cheerleader. I sense her in my torso nudging me forward with momentum. This part knows firsthand about the power of IFS and has seen hundreds of examples of it meaningfully impacting people’s sense of agency and fulfillment at work. This part hopes I can convey information well so that others may benefit from this powerful tool. Her motto is “LFG!”

One part wants the article to be perfect and artful. This part is like an old-man librarian, fastidiously hovering above a desk. He is primarily concerned about quality and things being just right, and demands that I capture nuance well. His motto is “That’s not quite right.” This part keeps me working long and hard on the perfect sentence.

One part is nervous and anxious. This part takes the form of a cricket, making loud noises and alerting me that something may go wrong, or that I won’t be effective at explaining this concept. It worries that I will fall flat, embarrass myself, or sound incompetent, so it ensures I do everything possible to avoid that. Its motto is “This is (going to be) bad.”

One part is concerned with having fun. This part is kind of a hippie, and likes to frolic and play and not worry too much about work. Her intention is to ensure I don’t spend my entire life working tirelessly without enjoying myself, and has a motto of “Good enough!” (She’s often in conflict with the old-man librarian, which leaves me both paralyzed and overwhelmed.)

One part is focused, assessing and tracking. This part sees the big picture and knows what’s missing, while also monitoring and assessing my progress at all times. His intention is to ensure the project gets done on time and to expectation, and his motto is “Let’s stay focused.”

One part is creative, and excellent at connecting dots. This part reminds me of all the relevant examples that might be included in the piece and offers me lots of metaphors to try to convey the message more meaningfully. Her hope is that things feel right and coherent, and her motto is “Ooo, what about if [new idea here]?”

As you can see, it’s quite loud in here!

When I sit down to write, the biggest productivity battle is actually an inner conflict between the old-man librarian (who wants things to be perfect), the anxious one (who thinks I’m going to fail or embarrass myself), and the free-spirit hippie (who likes prioritizing play over work, so would rather I not write at all). Then there’s the one trying to keep me on track and noticing whenever I get even slightly behind schedule.

These parts get very loud whenever I try something new or risky. The tension between these parts means that I spend a lot of time trying to write but instead end up procrastinating by doing unnecessary research, convincing myself I’m hungry, or opening up WhatsApp to chat with friends instead. This doesn’t feel good, and it doesn’t actually satisfy any of my parts. My ability to relate to them well (and integrate them rather than have them take over driving the bus) is the biggest determining factor of a productive writing day.

This is a third key principle of IFS: We all have a Self that can help us relate to and integrate the various parts on the bus. Ideally, this wise inner Self is firmly in the driver’s seat most of the time. This is critically important. We move through inner conflict by effectively facilitating dialogue, which requires a calm, safe, and compassionate presence available to all of us. That’s where we’re headed in the rest of the article.

Now that we’ve got a sense of some basic principles of parts, we can start to make progress on any inner conflict that’s leaving us stuck or overwhelmed.

I know it can be hard to apply some of these concepts just from an article. To bring this process to life, Lenny and I recorded a small session to give you a sense of what the exploration can sound and feel like. I’ve included snippets of each step below, but know that getting through even just step 1 or 2 can provide great relief.

First, let’s meet and get to know our parts.

Step 1: Sense and name the competing parts

Your parts are at play all day, so it doesn’t have to be a radical, huge conflict to recognize them more formally. Bring a challenge to mind and inquire how you’re feeling about it, and you’re likely to experience different parts of you reacting to that challenge.

Here’s an example that will resonate with any startup operator:

One part tries to help you focus on the big picture, and another part reminds you of all the small things you need to get to and the meeting you have in five minutes that you still haven’t prepared for. Observing this tension, a third part comes in and reminds you that you’re bad at getting stuff done and questions why it’s always so hard to be productive.

The dialogue continues, and pretty soon the tension grows such that each part takes on an even more extreme version of their role.

Sound familiar? It’s common, it’s normal, and it’s exhausting. Every one of us has these internal dialogues, and they can get especially loud when we’re stressed, overwhelmed, or feeling any personal threat (aka: startups).

I have clients visualize the conflict as one part on the bus grabbing the steering wheel and driving in one direction, only for a different part to grab the wheel moments later and take a completely different route. Back and forth, over and over again, and the bus goes nowhere.

Acknowledging what parts are at play and naming the conflict alone can be transformative. When we see the tension clearly, that can sometimes be enough to dissipate it.

This process of sensing your parts can be quite simple. Let’s look at how Lenny does it in this first clip.

When imagining the upcoming Lenny and Friends Summit, he quickly notices three different parts that show up in anticipation of the event.

Here are some tools to sense your own parts:

Notice what’s happening in your body. Parts can reveal themselves as thoughts, images, words, visuals, sensations, and emotions.

Slow down so you can track what’s happening. Fast thinkers, especially, tend to go quickly over their own experience. Try to stay with it for a bit longer.

Imagine giving voice or a microphone to different sensations as you feel them. If this sensation had words, what would it say?

You might also ask yourself how you feel about a part that comes up. We’re looking for an open, compassionate heart. If you feel frustrated, annoyed, or judgmental . . . chances are you’ve found a different part that’s in some tension with the first.

Step 2: Validate that each part of you is valuable and wise

If you grew up in a house with siblings, you know that favoring one kid usually doesn’t end well. Yet most of us tend to favor one part of ourselves and shove the others to the side. That impulse is often driven by shame, guilt, or embarrassment.

Gustavo wanted to see himself as someone who got stuff done, so he sided with the part of himself that confirmed that identity (the time management one) and pushed away any part of him that wanted to prioritize rest or work-life balance (like the exhausted one). He (really, another part of him) judged those parts as unproductive and shameful.

But the parts that we judge, shame, or ignore actually tend to get louder and more extreme as we try to ignore them. The goal is to recognize each part as equally valuable, wise, and worthy of listening to. It’s a powerful healing experience to actually have our own experiences validated. This alone can create a shift and more ease without having to do or change anything. Once our parts feel heard, they are usually flexible and trusting of an adult in the room (you) to make decisions on their behalf.

At this step, I tell my clients to bring the conflict to life using names or identities where resonant—as I did for the parts of me writing this post. For example:

“The ambitious part of me wants to take on more work. The balance part of me wants to prioritize rest and relaxation.”

“One part of me wants to make a strong and bold decision. Another part of me feels insecure about the decision and is scared I’m messing it up.”

“The warrior in me thinks I should give this feedback now while it’s fresh. The janitor in me doesn’t want to cause drama and experience discomfort so would rather sweep it under the rug.”

Then notice if there’s one you favor, or one that usually “wins.” You can do this by imagining which voice on the bus is louder, or by having each part sit in your hand while you assess their relative weight. These are techniques for recognizing the polarization itself. What’s important is to feel it, rather than just intellectually understand it.

In this next clip, watch how Lenny beautifully tracks the internal conflict as I mention there may be validity and wisdom to his fear. During this process, we’re shifting from a part that wants to fix and squash his fear to a more compassionate place of trying to validate and understand how the fear helps him.

Step 3: Pull the bus over and listen

When we work on inner conflict, the goal is not to override one side or let anyone “win” but instead to facilitate better ongoing internal collaboration so that they can work together on the same team. To do so, we need to listen to both sides.

In IFS, we call this process “unblending.” In our bus metaphor, unblending is like saying, “Hey, part, I need you to step away from the steering wheel so we can pull the bus over and I can first understand where you want to go and why.”

We do this with all parts involved in the internal conflict. I have my clients interview (not interrogate) the parts with an imaginary microphone and really get the full download. This can feel silly if you’ve never done it before, but it’s surprisingly powerful because many of these parts have never received undivided attention and curiosity.

As you interview and listen to each part to understand its feelings, needs, and fears, it’s very common for another part on the bus to suddenly come in, grab the steering wheel and give you contrary evidence that proves, criticizes, or distracts.

When this happens, imagine pulling the bus over again. We’re not driving anywhere else until we understand and listen to where everyone wants to go, but we have to do that one part a time.

Interview as many of the parts as need to be heard in the inner conflict. These parts are trying to protect or serve you in some way—even your inner critic!—and your goal is to help them feel known and understood in their efforts. Often these parts will share fundamental concerns (even if they respond to those concerns in opposite ways).

Let’s see how Lenny does this with the part of him that’s scared about the Summit, and the part that motivates and pumps him up to do a good job.