👋 Hey, I’m Lenny and welcome to a 🔒 subscriber-only edition 🔒 of my weekly newsletter. Each week I tackle reader questions about product, growth, career, and everything else that’s stressing you out about work.

Happy new year!

Over the holiday break I was reading Hit Makers by Derek Thompson (thanks, Gabor Cselle, for the recommendation!), and one of the chapters forever changed the way I think about growth. I’m curious if you feel the same after reading this post.

Hit Makers is about how hits become hits. Why do some songs, books, movies, and products win, while others don’t? What ingredients do they have in common, and what drives their success? Derek Thompson wanted to find out, and he ended up dispelling a number of myths along the way.

One of his most surprising findings (at least for me) was that going “viral” is mostly a myth. We think that products often grow through friends telling friends, who tell more friends, and this cascades to so-called viral growth. It turns out this is almost never how products grow. Instead, products explode in popularity when someone (or a few someones) with a large platform shares the product with their audience.

Here’s Derek Thompson describing this phenomenon:

“People are social creatures—they talk, they share, they pass things along. But unlike with an actual virus, a person chooses to be infected by an idea, and most people who confront any given thing don’t pass it along. Viral diseases tend to spread slowly, steadily, across many generations of infection. But information cascades are the opposite: They tend to spread in short bursts and die quickly.

The gospel of virality has convinced some marketers that the only way that things become popular these days is by buzz and viral spread. But these marketers vastly overestimate the reliable power of word of mouth. Much of what outsiders call virality is really a function of what one might call ‘dark broadcasters’—people or companies distributing information to many viewers at once, but whose influence isn’t always visible to people outside of the network.”

In a recent interview on the Acquired podcast, Ben Thompson (author of Stratechery) shared this same finding from his personal experience:

“The problem with a word-of-mouth business and exponential growth is people run out of people to talk to. That’s the limiting factor. There’s a little bit of exponential with every new subscriber, because they will tell new people, but networks get exhausted.”

My argument in this post is this:

True virality rarely exists.

When it does, it’s very short-lived, and quickly reverts to linear (or worse) growth.

When we see a product going “viral,” it’s very rarely driven by a many-to-many spread, but is instead the result of someone with a large audience broadcasting it (i.e. one-to-many).

Even though products don’t grow virally for long, it’s still absolutely worthwhile to optimize mechanisms of virality (e.g. word of mouth, invites, referrals, a remarkable product), since that can drive ongoing (free) growth.

At the same time, to ignite (and re-ignite) moments of “virality,” you’ll need to invest in getting large one-to-many broadcasts. For example, PR, influencers, TV.

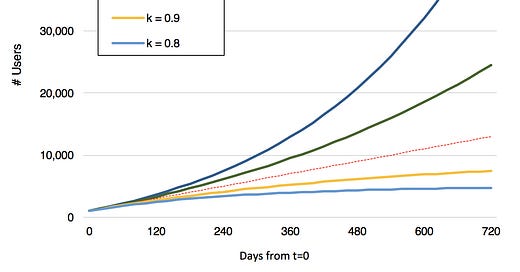

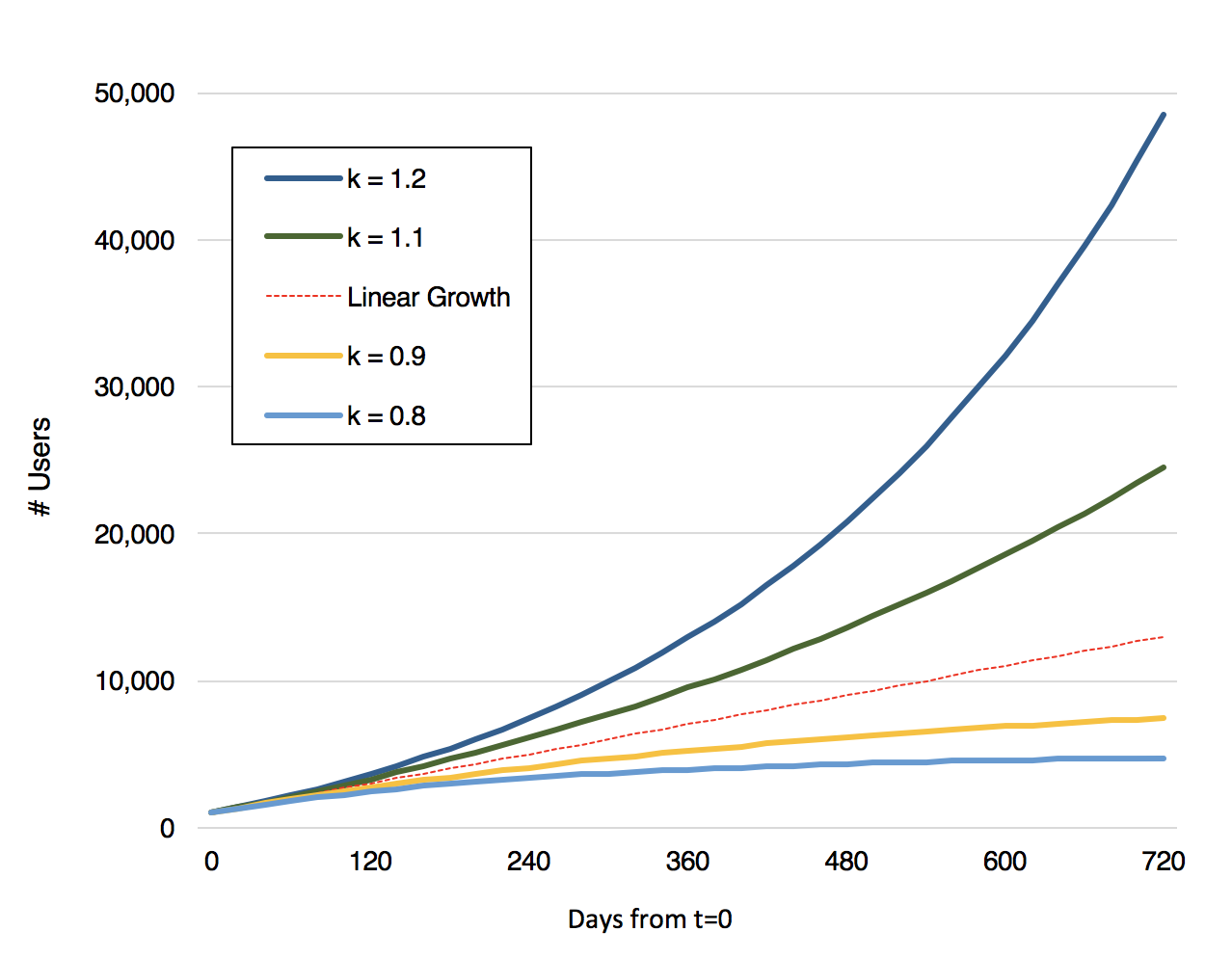

Before going further, let’s define virality. Something is viral when the average new user brings more than one additional user. This is often referred to as the viral coefficient, or k-factor, being higher than 1.0, and it looks something like the green or blue line:

When calculating k-factor for yourself, there’s an important nuance around the cycle time between new users and referred users (read more here and here), but for the purpose of this discussion, let’s keep it simple and think of viral growth as primarily self-driving (i.e. users bringing in new users), and faster than linear growth.

Let’s dive deeper by starting with this excerpt from Hit Makers:

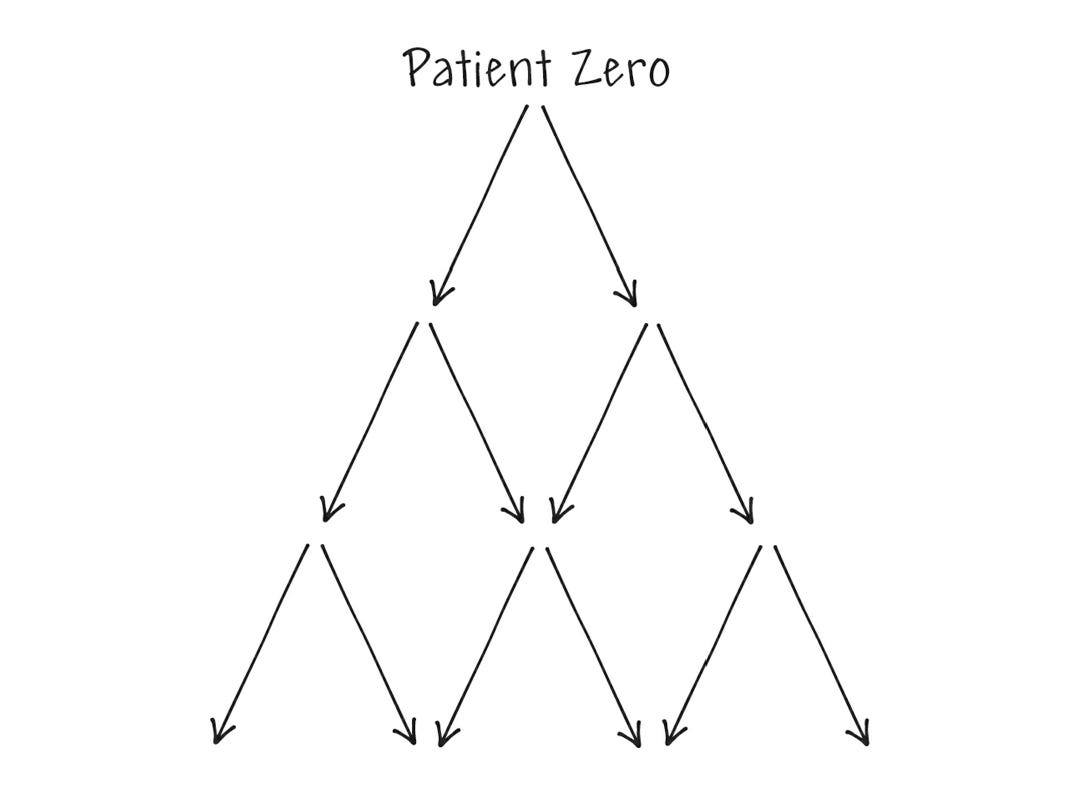

It’s become fashionable to talk about ideas as if they were diseases. Some pop songs are infectious, and some products are contagious. Advertisers and producers have developed a theory of “viral” marketing, which assumes that simple word of mouth can easily take a small idea and turn it into a phenomenon. This has fed a popular conception of buzz that says that companies don’t need sophisticated distribution strategies for their product to go big. If they make something that is inherently infectious, they can sit back and wait for it to explode like a virus:

In epidemiology, “viral” has a specific meaning. It refers to a disease that infects more than one person before it dies or the host does. Such a disease has the potential to spread exponentially. One person infects two. Two infect four. Four infect eight. And before long, it’s a pandemic.

Do ideas ever go viral in that way? For a long time, nobody could be sure. It’s difficult to precisely track word-of-mouth buzz or the spread of a fashion (like skinny jeans) or an idea (like universal suffrage) from person to person. So, by degrees, “That thing went viral” has became a fancy way of saying, “That thing got big really quickly, and we’re not sure how.”

But there is a place where ideas leave an information trail: on the Internet. When I post an article on Twitter, it is shared and reshared, and each step of this cascade is traceable. Scientists can follow the trail of e-mails or Facebook posts as they move around the world. In the digital world, they can finally answer the question: Do ideas really go viral?

The answer appears to be a simple no. In 2012, several researchers from Yahoo studied the spread of millions of online messages on Twitter. More than 90 percent of the messages didn’t diffuse at all. A tiny percentage, about 1 percent, was shared more than seven times. But nothing really went fully viral—not even the most popular shared messages. The vast majority of the news that people see on Twitter—around 95 percent—comes directly from its original source or from one degree of separation.

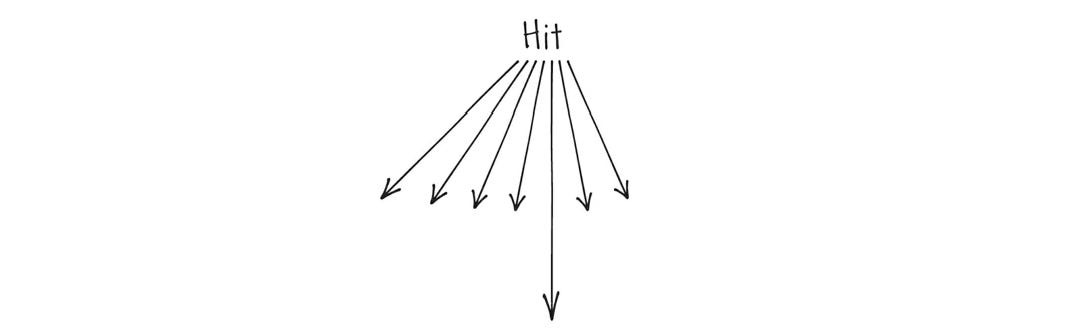

If ideas and articles on the Internet essentially never go viral, then how do some things still achieve such massive popularity so quickly? Viral spread isn’t the only way that a piece of content can reach a large population, the researchers said. There is another mechanism, called “broadcast diffusion”—many people getting information from one source. They wrote:

Broadcasts can be extremely large—the Super Bowl attracts over 100 million viewers, while the front pages of the most popular news websites attract a similar number of daily visitors—and hence the mere observation that something is popular, or even that it became so rapidly, is not sufficient to establish that it spread in a manner that resembles [a virus].

On the Internet, where it seems like everything is going viral, perhaps very little or even nothing is. They concluded that popularity on the Internet is “driven by the size of the largest broadcast.” Digital blockbusters are not about a million one-to-one moments as much as they are about a few one-to-one-million moments.

Extended to the full world of hits, this new finding suggests that articles, songs, and products don’t spread like in the first picture we saw. Instead, almost all popular products and ideas have blockbuster moments where they spread from one source to many, many individuals at the same time—not like a virus, but something like this:

Imagine you go to work on a Monday and a coworker tells you about a new guacamole recipe she read in the New York Times. Several hours later, you go to lunch with another coworker, who asks if you’ve heard about the new guacamole recipe he read about in the New York Times. After work, you go home to your spouse, whose coworker evangelized a new guacamole recipe she found in the New York Times. The common observation is: “The Times article about guacamole went absolutely viral.” But the truer observation is that the article didn’t go viral in any meaningful sense of the word. It reached a lot of people who read the recipe section of a large international newspaper, and a few of them talked about it.