How to validate your startup idea

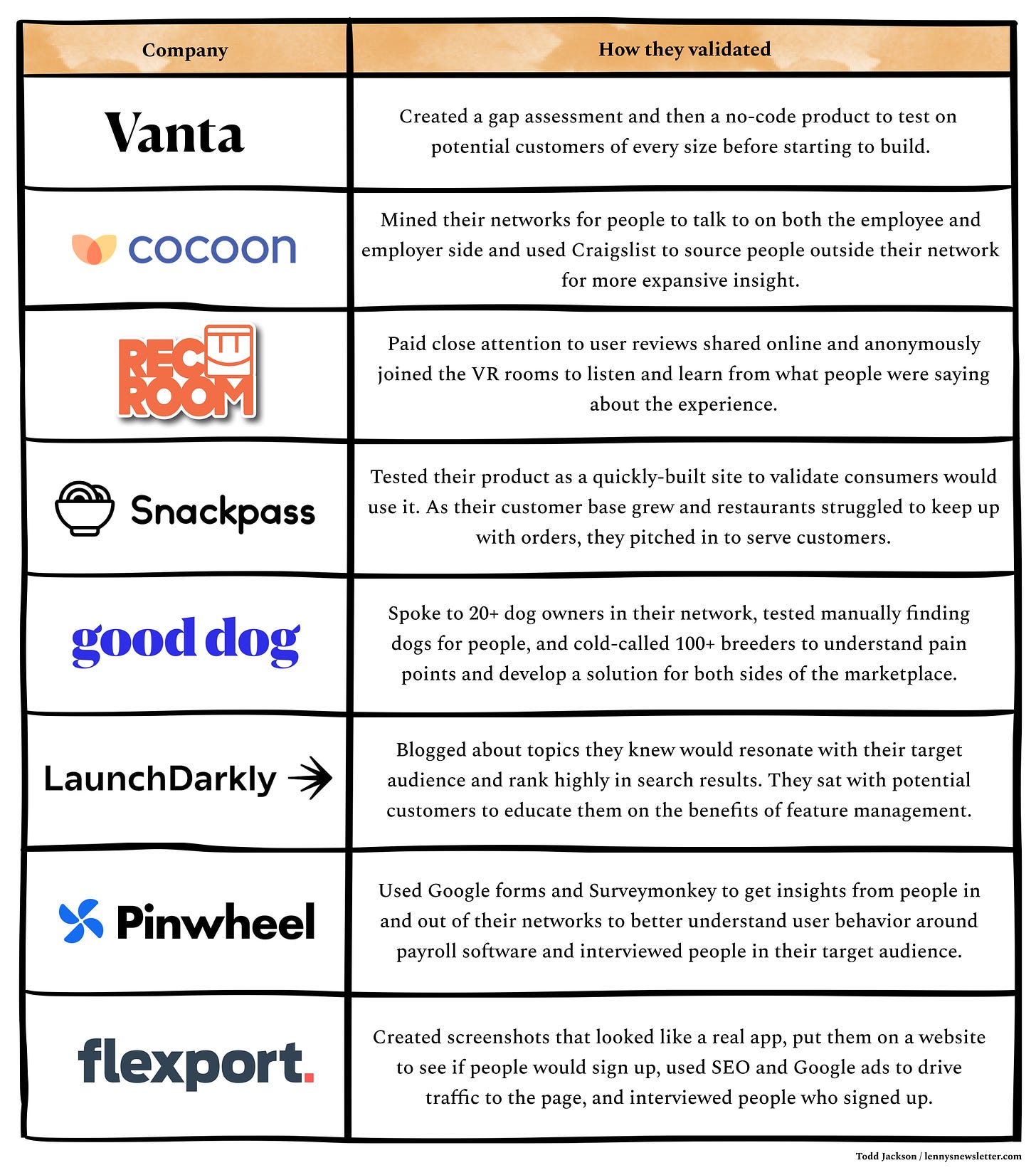

Lessons learned from Flexport, Vanta, Rec Room, LaunchDarkly, Pinwheel, Snackpass, Good Dog, and Cocoon—a guest post by Todd Jackson

👋 Hey, Lenny here! Welcome to a ✨ monthly free edition ✨ of my weekly newsletter. Each week I tackle reader questions about building product, driving growth, working with humans, and anything else that’s stressing you out about work.

If you’re not a subscriber, here’s what you missed this month:

Q: I have an idea for a startup. How can I validate that it’s a good idea, and how will I know when an idea is promising enough to commit to?

Committing to a startup idea is possibly the most consequential decision you’ll ever make. It’ll impact everything they do for the next 1 to 50 years, and either lead you to fame and fortune or a brick wall to endlessly bang your head against. No pressure.

To help you navigate this critical time, Todd Jackson (partner at First Round Capital) spent 2+ months researching, interviewing, and synthesizing lessons from some of today’s most exciting companies to understand what gave them the confidence to commit to their idea. Below you’ll learn how these companies come up with their idea, validated it, and gained traction—along with a host of lessons learned along the way.

In his nearly 20-year career, Todd has helped build some of the biggest products in tech that hundreds of millions of people use every day, from Gmail’s UX and Facebook’s Newsfeed, to Twitter’s timeline and Dropbox’s bottom-up revenue engine. He founded his own company, Cover, in 2013 and met First Round Capital when they led his seed round. Now at First Round he helps early founders launch and grow their businesses. You can find him on Twitter and LinkedIn.

As a seed-stage investor at First Round Capital, I get to meet a lot of founders who are exploring and validating their ideas. It’s an exciting time for them and, as a former founder myself, I relate to the thrill and anxiety of just getting started. You believe you’re onto something and feel ready to bring your idea to life, but there’s also a lot of wondering, Am I crazy to pursue this?

While there’s no single right way to get started or build a business—and timing, luck, and grit often play an outsize role—over the years, I’ve observed a few commonalities in how strong businesses got their start. From my own startup ideas (more on that here) and from talking to many successful founders, I’ve seen a few clear patterns around how people come up with their ideas, validate them, and build the conviction they need to go all in. There may not be a single playbook on how to build the next unicorn, but you can learn a lot from reverse-engineering how the best entrepreneurs went about building their companies.

To give you some recent examples of the path from initial idea to success, I interviewed the founders of eight companies and spent many hours over the past two months digging into their incredible stories:

Christina Cacioppo, CEO and co-founder of Vanta

Ryan Petersen, CEO and founder of Flexport

Mahima Chawla, CEO and co-founder of Cocoon

Josh Wais and Lauren McDevitt, co-founders of Good Dog

Edith Harbaugh, CEO and co-founder of LaunchDarkly

Kurtis Lin, CEO and co-founder of Pinwheel

Here’s what I learned.

How do I pick an idea and validate it?

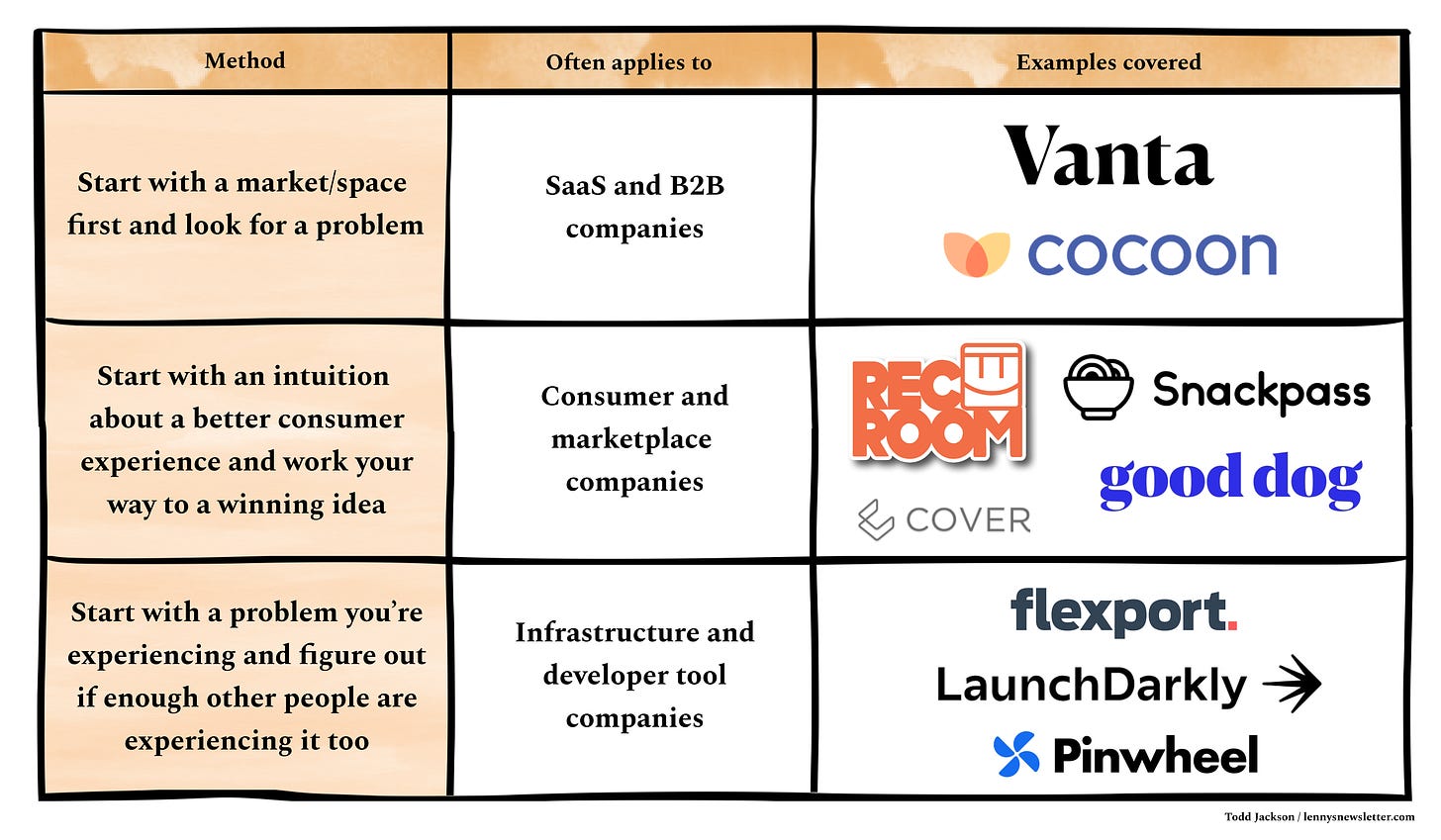

Based on my research, there are three common ways to come up with an idea:

Market first: Start with a market or space that interests you, then look for a specific problem.

Experience ripe for improvement: Look for areas where you believe there should be a better consumer experience than what currently exists, and iterate from there.

Problem first: Start with a problem you’ve experienced firsthand and figure out if enough other people have the same problem.

These methods tend to correlate with specific categories of companies:

Let’s look at examples of how the founders I talked to used each method to come up with an idea, validate it, and gain confidence that they were on the right track.

Start with a market/space first and look for a problem.

If you already have a particular market in mind, talk to people in that space to more deeply understand their experience and challenges. There’s no set number of conversations to have, but I’ll offer suggestions near the end of this article. You want to look for a burning pain that’s so bad, customers will literally try anything to solve it.

Christina Cacioppo is the CEO and co-founder of Vanta, an automated security monitoring platform that helps companies get SOC 2, HIPAA, or ISO 27001 certified quickly. Launched in 2017, Vanta has over 2,800 customers today and has raised $55M.

Finding an idea

Christina started out on a couch with her co-founders, tossing around ideas for several months. Her advice? “Don’t do this.” She elaborates that when you’re at the idea stage, it’s easy to poke holes in everything if you ideate in a bubble: all the ideas are flawed, you’re limited by what you already know (which might be a lot, but it’s still a small subset of what the market knows), and it’s hard to get real feedback from anyone when you’re just talking through hypotheticals. Instead, she recommends getting out into the market, having conversations, and testing early models.

After testing a few prototypes that didn’t work out, Christina decided to investigate the security space out of naive interest.

“Securing the internet seemed important, particularly around the recent 2016 election and Equifax breach, and yet the tech industry seemed really bad at it. Why? And why are there so many cybersecurity companies and yet no startup uses any of them?” —Christina Cacioppo

She started by interviewing founder friends and security leaders and asked them about the best and worst part of their days. She heard many answers, and tried and discarded several different ideas. But when she heard about security being a blocker to companies moving upmarket and unlocking revenue, that’s when she started to feel real interest from the people she spoke to. Digging in deeper, Christina and her co-founders discovered that SOC 2—often the first way a company needs to prove its security competency—was a major pain point and, while security consultants offered expensive help, many people wanted an easier solution.

Validating the idea

They started by developing a gap assessment similar to what a SOC 2 consultant would create, with the goal of confirming they understood the requirements of the SOC 2 process and that it could be broken down into simple steps. After hearing a strong desire for a “SOC 2 easy button” solution, they built a zero-code MVP (a spreadsheet) to test with potential customers and determine whether SOC 2 preparation was actually productizable. Both founders were skilled at product development but had learned the hard way not to write code until they’d validated that people wanted the product.

Christina shared this MVP with friends, former coworkers, and people in their networks at companies ranging from two-person startups to multi-thousand-person enterprises to gauge their reactions. She knew they were onto something when she got a call from a friend out of the blue saying, “I heard you’re doing SOC 2. We should get a drink, and also can you do that for my company?” As more people proactively reached out to ask about what she was building, she got a real sense of market pull, which led to growing confidence.

Christina didn’t try to segment her customers by total addressable market (TAM) but instead went where the pull felt the strongest. From her customer discovery conversations, she not only validated product-market fit but also found that selling to smaller startups would initially be easiest because those founders were most eager to get their SOC 2 report in hand. As the co-founders continued building, they found that small startups were seeking SOC 2 earlier and earlier—for example, fintech companies like Modern Treasury got their first SOC 2 report when the teams were just the founders.

💡 Moment: When people whom Christina hadn’t even spoken to started reaching out directly to ask about using Vanta.

Finding traction

They joined Y Combinator, kept building the product, and completed their first full audit with a customer in November 2018. By the end of the year, with seed funding, a nascent team, and 30 customers, they suddenly realized, “Wow, this is working better than it should.”

While raising their seed round, Christina was routinely asked, “How many startups, especially small ones, really need SOC 2?” At the time, they believed there were maybe 600 companies in the world that would need SOC 2. The co-founders knew that was too small of a TAM for a compelling venture-scale business, but they bet that as the technology evolved, software security would change and the need for SOC 2 would continue to grow. That prediction ended up coming true faster than they expected. Today, Vanta has thousands more customers than they even thought were in the company’s initial market.

What advice would you give a founder just starting out?

“Do all the product development best practices [market research, user interviews, validating mockups before building, starting with a lightweight MVP to test the core problem].

Nobody wants to do them because they seem tedious, they’re less fulfilling than building, and when you’re excited, you just want to get started. But these steps make such a difference. It’s so easy to change a spreadsheet or mockup; it’s much harder to change code.”

Quick tips:

Build prototypes and test your early ideas on real customers; listen to their responses, and anything short of “I want this!” is really a “No thanks.”

Don’t build a full product until you’re feeling real pull from the market.

Figure out who you can sell to most easily, and start there. Market analysis can come later.

Develop a product that unlocks revenue for your customers.

Mahima Chawla is the CEO and co-founder of Cocoon, an employee-leave platform designed to empower companies to better support their team members through life’s most pivotal moments. Founded in 2020, Cocoon has raised $26M and seen rapid customer growth since its initial launch.

Finding an idea

Mahima and her co-founders, Amber Feng and Lauren Dai, started by exploring pivotal life moments, particularly around the significant transition to becoming first-time parents. They interviewed dozens of parents to surface the challenges faced during that major life change. Initially their interview script was open-ended around financial planning, but conversations consistently steered to the problematic topic of leave. They heard about big pains over and over.

“In other areas, we were searching for the problem, whereas with leave it was obvious.” —Mahima Chawla

Validating the idea

This prompted the team to start a deep exploration into the world of leave. They heard about the challenges of state and federal regulations. They heard crazy stories, including one where a coworker brought her laptop to the hospital for her C-section and was applying for California state EDD benefits while being wheeled into the OR so she would be paid during leave. After exhausting their own networks (which tended to be tech employees), they put an ad on Craigslist to talk to a broader audience that included hourly workers. The nightmare leave stories continued: not getting paid in full, not knowing they had the option to take federal- or state-entitled leave, drowning in paperwork, spending 10 hours on hold trying to track down state and private insurance benefits, and more.

Once it was abundantly clear that leave was a pain point for employees, they did similar research on the employer side. Talking to dozens of companies confirmed that leave is an absolute nightmare, both for administration and employee experience.

With conviction in the opportunity, Mahima, Lauren, and Amber limited their initial scope to addressing parental leave in California. They began by designing a UI flow in Figma, which they shared with the employees and employers they’d previously interviewed. The general reaction was that it was almost too good to be true: “I’ve never seen something like this before” and “I’ll believe it when I see it live!” They signed their first two customers—Carta and Benchling—off the Figma prototypes, which strengthened their confidence that they were on the right track.

💡 Moment: Strong positive feedback from both employees and employers on product mockups of Cocoon—including selling their first customers based on Figma prototypes!

Finding traction

The Cocoon team raised a seed round in December 2020 and started building the product. While they’d validated that all types of employers in the U.S. and Canada, regardless of size and industry, needed a leave solution, they started by focusing on parental leave for companies in California, Utah, and Pennsylvania with 100 to 200 employees (the stage of growth when the challenges with leave administration start to surface). They expanded quickly to all 50 states and added medical leave.

They used outreach to their networks early on to find companies interested in using Cocoon but soon had an influx of inbound leads from word of mouth and their website. That rush of interest gave them confidence that they were on the road to success (a pattern we’ve seen in both the Vanta and Cocoon examples!).

What advice would you give a founder just starting out?

“Go in with a very open mind. Don’t try to make something a problem, because if you do you’re going to find the evidence to support it. Really just truly listen to what the person you’re interviewing is actually saying and notice if there is a trend.”

Quick tips:

If it feels like you’re pulling teeth to find the pain point, you haven’t found a problem worth solving.

If you’re building a marketplace or platform for multiple audiences, be sure to validate the pain points for each persona you’re targeting.

Use an MVP or mockups to get early customer feedback before you build.

Inbound demand is a strong signal you have product-market fit.

Start with an intuition about a better consumer experience and work your way to a winning idea

Other founders, particularly those building consumer or marketplace companies, start with an intuition that there should just be a better consumer experience and set out to build it. This approach still takes a lot of conversations with consumers to pinpoint exactly where they’re experiencing pain, in and around the hunch that got you started. Start with your intuition, but don’t let it be the only information that informs your approach—unless you’re happy being your only customer.

Josh Wais, CEO, and Lauren McDevitt, Chief Experience Officer, co-founded Good Dog to make it simple to get a dog responsibly. Started in 2018, Good Dog has now raised its Series B.

Finding an idea

Back in 2010, Josh and Lauren started an online shopping platform called Wantworthy that didn’t work out, because it required consumers to adopt a new behavior. They wanted to try again, approaching the fresh start with a clear view of what it takes to create a successful company. They explored a number of ideas but were struggling to find a good one that leveraged their strengths and had a mission they felt passionate about.

“For somebody entrepreneurial, you want to start a company, but you have to wait for the right thing to hit you personally and logically.”

—Josh Wais

They found that idea in the concept for Good Dog. Both Josh and Lauren had experienced firsthand the challenges of finding a dog. As they talked to more people, they heard that others had faced these problems too—long waitlists, finding the right breed, finding a reputable breeder or shelter/rescue, avoiding potential scams, etc.—and saw the effects this had on both people and dogs. They saw an opportunity to create a marketplace bringing together reputable sources for getting a dog with consumers who wanted a trustworthy, confidence-inspiring, convenient experience. This mission felt more compelling than anything they’d worked on before, and they were excited about the prospects of creating a better system.

Validating the idea

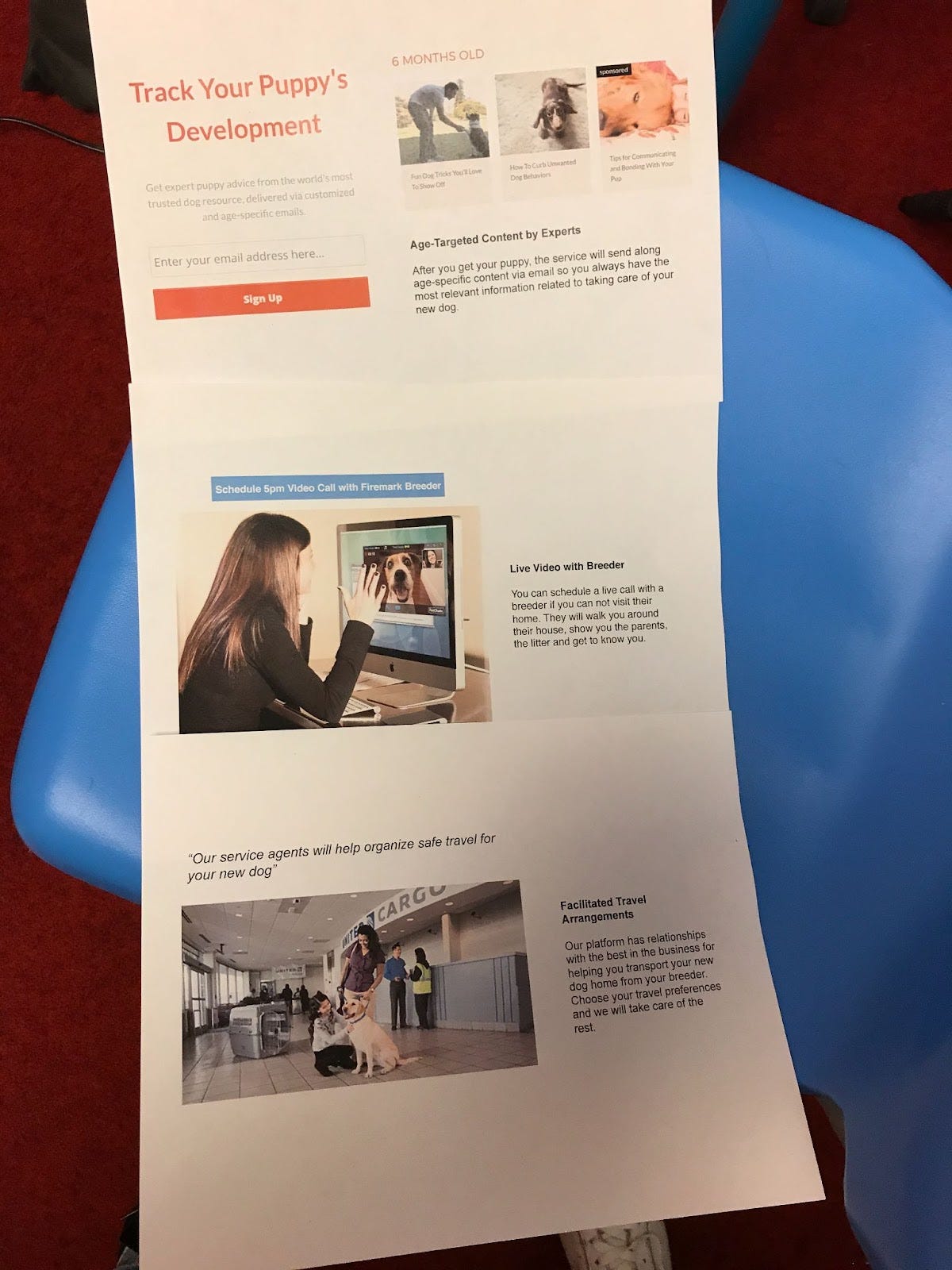

Lauren’s background in product helped them employ design thinking to shape their validation process. She used “sacrificial concepts”—low-fidelity concepts that could be printed out and put in front of consumers to test different adaptations of potential solutions. They asked friends and colleagues if they knew of anyone who had recently gotten a dog or was looking for one. Since people tend to talk about their dog search process, they were able to find a lot of subjects to interview. They also compensated participants for their time to reduce bias by making it less about the person doing them a favor.

They then did a series of 20+ dog owner interviews, asking people to walk them through the whole process with questions like How did you decide you wanted to get a dog? What was the most painful part of the process? Which part was most exciting?

After a month of interviews, they’d learned that people struggled or even gave up trying to get a dog because it was such a time-consuming and challenging process. Pain and hassle were consistent themes across almost every conversation. Finding so many pain points around trust and convenience in an area so personally important to people gave them certainty that they were onto something big on the demand side. To confirm their hypothesis, they experimented with finding dogs manually for hopeful owners and discovered there were a lot of people who were desperate for assistance.

They then worked on validating the supply side of the marketplace because it was critical to have trusted, quality breeders on the platform for the community to work. This part turned out to be more challenging—they worked on it nights and weekends for six months, cold-calling hundreds of breeders and trying to get them to answer questions. Josh and Lauren didn’t know exactly what the value proposition would be for breeders, but they had so much conviction on the consumer side that they were determined to crack it. “We need to figure out the specifics, but we believe in the vision of where we’re going,” they said.

Finding traction

It took a full year to crack the supply side of the marketplace. Josh initially cold-called breeders using a script that felt painful and awkward to him. Then he had a revelation: if he explained the mission and that he was focused on recognizing responsible breeders and then dove right into the screening questions (i.e. starting with the hardest part), the breeders he called were much more inclined to engage. That approach tapped into the breeder’s pride and passion for their dogs, as well as the effort they put into their work and the welfare of their dogs.

Good Dog went live with 300 breeders on the platform in March 2019 and started using Facebook ads, initially to build brand awareness with breeders and then shifting into informational content. Three months later, they had 600 breeders and a strong enough reputation to focus on adding a sign-up flow to the site.

By the end of 2021, they had over 20K breeders live on Good Dog. Josh says, “The goal we set out, to become the go-to platform for responsible breeders, is now within our sights. Of the estimated several hundred thousand breeders in the U.S., over 50K have signed up to be on Good Dog and are either live or we’re screening and helping to onboard or bring up to our standards.” They’ve successfully built a community dedicated to advocating for responsible breeders and helped hundreds of thousands of people in their dog search.

💡 Moment: On the consumer side, it was hearing about the deep pains people encountered, including giving up on their dog search altogether. On the breeder side, it was discovering that tapping into breeders’ pride in their work and passion for ethical treatment of dogs motivated them to engage with a new startup like Good Dog.

What advice would you give a founder just starting out?

“Put in the work to try to gather as much information as you can to understand the underlying motivations/needs of users and the dynamics of the market you’d be entering up-front. You don’t want to be blindsided by something that’s fundamental later. Better to know early on to understand if it’s worth moving forward, and if so, you’ll be prepared to work through it.

And don’t ignore your gut and how you personally feel about the idea and mission. You’ll face more than just the one challenge of finding PMF at the beginning. There are a lot of steps you’ll need to work through to bring your company to life. Having belief in your idea and feeling it in your core is really important. Believing it should exist and having information to support that is really critical. Everything after that is problem solving.”

—Josh Wais

Quick tips:

Don’t rush into just starting a company—wait for the right thing to hit you personally, emotionally, and logically.

Be clear-eyed about what it means to start a venture-backed company.

Be self-aware about what you know and don’t know.

Kevin Tan is the CEO and founder of Snackpass, a social commerce platform that focuses on mobile order pickup at local restaurants. Founded in 2016, Snackpass has raised $96.5M to date.

Finding an idea

When Kevin was in school at Yale, there was a big culture around going out for food after class or late at night, particularly at a really popular place called Gourmet Heaven (“G-Heav”). It was ridiculous pandemonium every Saturday night when people would struggle to even place their orders. Uber Eats had just recently launched, but students were still going to pick up their food and it was a crappy process, a bad customer experience, and a likely cause of lost revenue. Kevin envisioned a future where people could order ahead and skip the lines entirely.

Validating the idea

With this insight in mind and the desire to create something his roommates would love, Kevin tapped into relationships with a few local restaurant owners he’d built websites for in the past (including G-Heav) and went door-to-door to talk to the owners. He convinced them to join his new website to reach more customers, grow their brands, and offer discounts to verified students. He then built the website over Thanksgiving break, used an API to send orders to the restaurants by fax machine, and launched with five restaurants.

In December around finals week, Kevin printed flyers and distributed them across campus to tell students about the website that would give them discounts and let them skip the line at participating restaurants.

“It was amazing. It was the first time people signed up for a product I’d made. It was a trickle at first but kept growing and growing.”

—Kevin Tan

Finding traction

Kevin saw signs of traction from the beginning, and within six months everybody on the Yale campus was using it (he estimates 90% of students!). The team created a mobile app for a better customer experience, added more restaurants, fixed a lot of bugs, and added the social layer that makes Snackpass stand out today. That social layer made it much easier for Snackpass to naturally spread, since the team didn’t have enough money (after being rejected from both YC and school funding) to offer cash incentives like referral bonuses for inviting friends to the app. They implemented a social points system, inspired by the Starbucks app, to reward users for orders and let them send points to friends on every purchase. Restaurants loved the idea because it drove word of mouth at no cost to them.

Kevin and his team worked on the app over summer break, and when students came back in the fall, the response was overwhelming. Restaurants would call the Snackpass team to say they needed to shut down because they couldn’t keep up with incoming orders. Instead, the team went to the restaurants and pitched in, washing blenders and helping with deli orders to keep customers happy.

At their second school, Brown University, the team had to overcome a lot of the same hurdles they’d experienced at Yale. Scaling the supply side was the primary bottleneck, so they built features to help restaurants onboard faster. The expansion to Brown was the first test of whether Snackpass was just a Yale phenomenon or had potential to be much bigger. By the end of the semester, Snackpass had taken off at Brown too.

Kevin attributes their success to focusing on three core value propositions—saving time, saving money, and connecting with friends—and making all product and resource decisions with those in mind.

💡 Moment: Seeing Snackpass take off at Yale through social mechanics and supply-side hustle, then repeating that same success at Brown University.

What advice would you give a founder just starting out?

On finding an idea

“It’s natural to think about things in trends, but there’s a great framework—the jobs-to-be-done framework—that says people hire products to get something done. That’s a more sane way to look at it than trying to map a trend.”

On the art of advice:

“Nobody ever gets penalized for giving bad advice. If you try to use heuristics as a cookie cutter, you’re going to run into some things that don’t work. All cases are different.”

Quick tips:

It’s OK to do things manually to get in front of customers and see if your idea works.

Thoughtful social integrations (like gifting reward points) can unlock substantial growth.

Find traction in one market before expanding into others.

Remain laser-focused on your core value propositions and vet new ideas against whether they deliver on those values.

Nick Fajt is the CEO and co-founder of Rec Room, an online universe that enables users to play and create games with friends. Founded in 2016, Rec Room has raised $294M.

Finding an idea

Back in 2016, Nick and the five other Rec Room co-founders were part of a group at Microsoft working on what would eventually become the HoloLens (a head-mounted display for AR tech). While building games and social apps for it, they realized the app model was fundamentally wrong. They were using the model of tiles that wrapped around your head, but the tiles didn’t work together. You could play with a pet in a pet app, chat with your friends in a social app, and visit Machu Picchu in a travel app—but you couldn’t go to Machu Picchu with your friends and let your pets run around. The team had the idea to figure out a different, richer app model where people could build rooms and objects and interact more across experiences.

Nick wanted to make it possible for an object authored by one developer to work in space made by another, and he envisioned a social substrate that would stitch all these experiences together. He and the five others formed Rec Room to explore building a platform, developer tools, or their own engine but figured they’d be “wildly unsuccessful because there are six of us, no money, and a couple hoodies between us.” Instead they decided to start by building a game and slowly ladder up from an app that began as a toy but became a platform used by a host of creators from individuals to businesses.

Validating the idea

They built the first game within 90 days and launched it quietly on SteamVR, figuring nobody would notice. To get early testers, they set up in the lobby of their WeWork and asked people walking by to check out the app. They also posted on Reddit, asking people to try their new build and gave demos to investors from within the game. Nick describes the first app they built as “looking like Wii sports in VR with three really shitty, terrible rooms in it.” Yet people liked it.

“We were very surprised. It struck a chord somehow and had a weird, buggy charm to it.” —Nick Fajt

The Steam VR store at that time didn’t have any free content—existing apps had very expensive, limited content because the overall audience was so small—so the Rec Room team launched their app for free and immediately started picking up traffic. Says Nick, “I think what was pulling people back over and over was the social aspect. You’d land in a room and there were other people from all over the world wandering around. There was no menu—it would force you to be with other people and you could see and hear them. The human came through in a way that’s hard to describe.”

People in the app could play games (paddleball, dodgeball, and disc golf), but the experience was very basic. Despite that, people were inventing other ways of interacting, such as putting on plays, hosting murder mysteries, or playing games like hide-and-seek that weren’t built in. This gave the team confidence that something was resonating—users were doing all sorts of things the team never imagined. Nick saw sparks of real love in the way people talked about the experience inside the app and in reviews.

💡 Moment: Early users showed signs of true passion, despite bugs and limited functionality. People found ways to invent their own activities that the team never predicted, showing they were immersed in the product.

Finding traction

After that first launch, the team got on Oculus and started adding other games like paintball to create a more playful version of the typical gory first-person shooter games topping the VR store charts. They also added quests—cooperative adventures that people would go on together. People loved paintball and quests (and still do today), but the team started realizing there was diminishing ROI because the user response gradually waned with each new version but Rec Room’s costs continued to grow. The team then explored user-generated content (UGC) by looking into what players were inventing on their own by taking over rooms meant for specific games and exploiting system bugs to do their own activities, some of which were particularly unexpected and impressive.

Growth continued steadily, but the team foresaw a plateau as the number of VR headsets available in the market topped out and the cost of creating new content grew. They leaned into UGC and launched on other screens (phones, game consoles, etc.) so people could play Rec Room outside of VR. Both caused intense audience backlash: VR players didn’t want non-VR players in the app, and everyone wanted Rec Room–generated content rather than potentially lower-quality UGC. In retrospect, while Nick recognizes that they should have evolved more slowly, he believes the changes were critical: “My view was that we’re not making enough money to operate this business, so we do this or we die.”

It took a long time for the UGC and cross-platform shift to take hold, but once again, Nick saw sparks of love growing in the community as people got more creative with UGC. Launching on PlayStation VR, Xbox, and mobile eventually helped them jump from 30K to 150K users each month. Four years later, Rec Room now has 3 million monthly active VR users, which is just a fraction of its total monthly active usership.

What advice would you give a founder just starting out?

On the highs and lows of being a founder:

“The absolute value of emotion you feel on any given day is way higher early in the founder journey. You can go from feeling on top of the world in the morning to feeling at the end of the day like the company is going to die next week. You’re going to be constantly surprised by the way people are using what you’ve built in ways that are inspiring, but you will also encounter problems that you as a 5- to 6-person company are horribly equipped to solve.”

On how relationships can support you as a founder:

“Optimize your relationships for the long term. That goes for your employees, your investors, your customers. You’re facing an existential wall, and it helps to have somebody who can just help you get through the next day or the next week. There’s all of these short-term decisions that feel like if you don’t take this sub-optimal path, you’re going to die, but it’s all about avoiding those traps.”

Quick tips:

You can build toward a big idea by starting with a small step that’s more accessible and affordable to launch.

Stand out from the status quo (e.g. whimsical paintball vs. gory shooters).

Watch how customers use your product to find inspiration for new features.

Listen to audience feedback, but balance it against doing what you believe is right for your company to survive and grow.

Cover was my own company, an Android app that launched in 2013 and reached 2 million users before being acquired by Twitter in 2014. My co-founders and I didn’t stick with it long enough to see continued traction like other founders I spoke to, but I wanted to include it to show a close-up of what it means to get scrappy and learn from your target audience.

Finding an idea

In 2012, the iPhone was dominant, and our idea was to target an underserved market by focusing exclusively on Android. People with Android phones were used to feeling like second-class citizens—cool apps like Instagram and Vine were iOS-only, and the whole Android UX in the early era (Froyo/Gingerbread/Honeycomb versions) was pretty unpolished. It was also an unfamiliar market to VCs—I didn’t meet a single VC in 2012 who used Android as their primary device.

Our thinking was that because of the developer capabilities available on Android, you could do cool things that were impossible to do on iOS, like modify the home and lock screens of the phone and access all the sensors. We envisioned creating a set of really cool experiences using those surface areas and had a ton of ideas around better app organization, surfacing better notifications and social updates, and generally just making the homescreen UI look cooler than the stock version. But we weren’t sure exactly which ideas would resonate most with users, so we turned to research.

Validating the idea

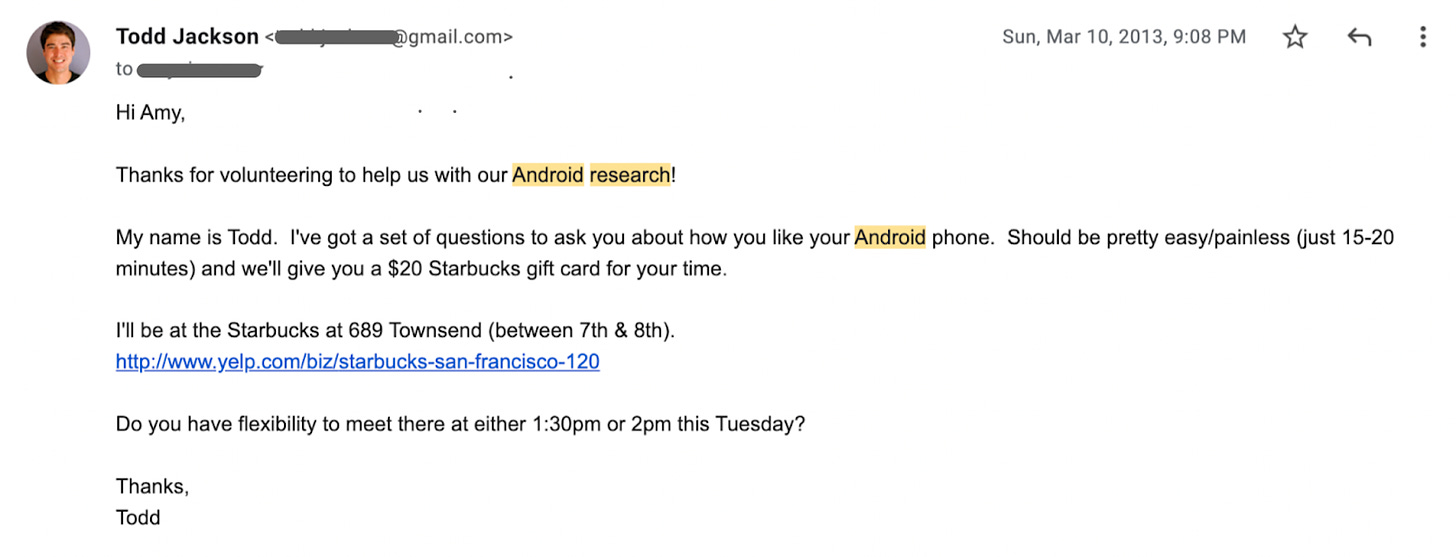

To better understand Android users, we posted an ad on Craigslist saying “Seeking Android users: $20 Starbucks card for 20min research interview (computer gigs).” When people responded to the ad, we sent them an email:

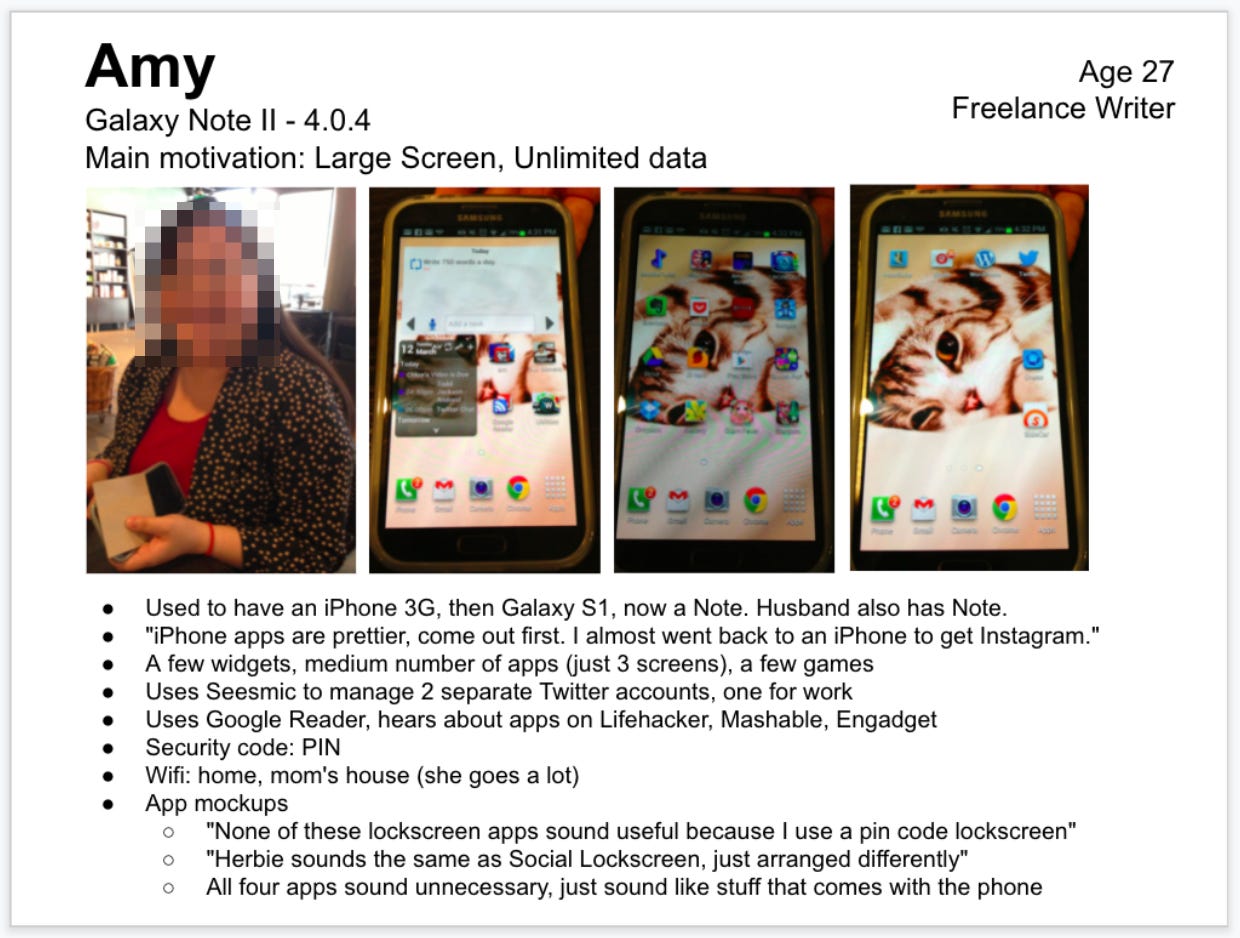

Then we camped out at several local Starbucks and interviewed each person who responded. We asked them why they chose their Android phone, what they liked and disliked about it, how they used it, and more. We then showed them various Play Store listings—some of which were real apps and others that I made in Photoshop (but we acted like they were real)—and asked for their feedback. Each interview was summarized into a simple dossier like this:

It was awkward and time-consuming but absolutely worth it. We talked to 30+ users total, all of whom were complete strangers from outside our personal networks. As a result, we were able to design an experience that resonated with a broad swath of Android users—and critically, to appeal to both their functional and emotional needs. The secret insight? A lot of Android users at that time were insecure about their phones and wanted to feel cool and edgy for choosing Android. We’d never have learned that without taking the time to ask questions for hours at Starbucks.

Finding traction

Within a few months, we had raised money from First Round and were building the first version of Cover. We arrived at a v1 design that offered utility in automatically organizing your apps but also looked sleek and changed the theme of your lockscreen based on your location. In both our product design and marketing materials, we emphasized that everything Cover did was only possible on Android—this was in direct response to learning from users that they wanted to feel cool and unique for choosing Android, not like second-class citizens to iPhone.

One of the best pieces of advice I got for driving a successful launch was from Gentry Underwood, the founder of Mailbox. Mailbox had grown incredibly quickly out of the gate because of its cool and innovative UX and excellent marketing. He told me that if you have a product that feels really interesting and different, strikes an emotional chord with users, and shows well in product demos, then the best way to launch that product is with a great demo video and an invite-only waitlist. It gets people really charged up: they naturally want to talk about the product, share the video, and eagerly anticipate their invitation.

We followed that approach, made a slick video, and sent it to all the big Android blogs (Android Central, Phandroid, Android Police, etc.) the night before launch. When we woke up the next day, it was on all their homepages. The response from the Android community was immediate—Cover appeared on dozens of sites, hundreds of tweets, and even a handful of teardown videos in the first week—because it was a polished app that was only possible on Android, addressing that emotional need we had uncovered in research. We got more than 100K waitlist signups in the first week, giving us a ton of momentum.

The mechanics of the waitlist turned out to be quite useful because it provided a community of users we could iteratively test on via different cohorts. On the waitlist sign-up page, we gathered information like what kind of Android phone they had, which version of the OS they were running, and what country they were from. We let in ~1k users each week with a new beta release and were able to target certain types of users based on what we were trying to test (e.g. we could release to 1,000 Samsung Galaxy users running on S3 hardware with a specific version of the Android OS).

This was huge in terms of helping us iterate and systematically refine the experience for different flavors of Android one by one. We spent about three months in invite-only beta, inviting wave after wave of users and steadily improving the product. We discovered our retention characteristics were generally binary—either users loved the app and kept it as their lockscreen (which they used hundreds of times per day) or they uninstalled it because it was doing something unacceptable like draining their battery. Determined to improve retention, we fixed compatibility issues, solved battery life problems, got location tracking working in different countries, and focused on making the app really solid.

💡 Moment: Tapping into a fervent community of Android enthusiasts and seeing them share the product, tweet about it, make their own teardown videos, and generally love and spread the app gave us a lot of confidence.

We reached 2 million users before being acquired by Twitter about eight months after launch.

I could go into a much longer story about why we decided to sell so quickly, but the primary reason was that we felt strongly aligned with Twitter’s mission and its desire to innovate more quickly on Android, but also because in the back of our minds we were worried about staying compatible with all the new versions of Android and continuing to innovate on what we suspected might become OS-level functionality at some point.

What advice would you give a founder just starting out?

“The biggest advice is simple—look for an audience that is large (or will become large) but is currently underserved, and then really take the time to dig in and understand their needs. Ask them questions, then another round of questions, and then another (sort of like the five whys). Don’t stop until you really understand the root causes behind their problems (again for us, it was the emotional factors around their relationship with Android). And then you can start testing solutions.”

Quick tips:

Seek out both functional and emotional needs from your users to make sure you build something that’s must-have, not nice-to-have (more on that here).

You need to really dig for the deep needs—users often can’t verbalize them directly.

Word of mouth can be your biggest driver. To encourage it, think about which communities might love your product and how a normal person in that community would describe it to a friend in their own words. Then use those same words yourself in the product, on your website, and in your marketing.

Start with a problem you’re experiencing and figure out if other people or companies are experiencing it too

You can also find a good idea by solving a problem you’re experiencing yourself. There’s a good chance that if you’re feeling the pain, others are as well. But don’t just assume this—you need to do the homework to make sure it’s a real and common problem. And it needs to be more than just a nuisance. No one pays for solutions to problems that aren’t impacting their lives or their revenue in meaningful ways.

I’ve seen solutions to lived problems most often in developer tools, infrastructure, and other B2B companies. Founders who experienced a problem at one company sometimes leave to start their own business solving that problem for other companies. If you’re starting a developer or API-focused business where you’ve lived the problem before, it’s critical to have a deep belief in the usefulness of your tool but equally critical to make sure there’s enough market pull for what you’re building from other developers.

Edith Harbaugh is the CEO and co-founder of LaunchDarkly, a feature management platform that allows software development teams to deliver to their customers. Started in 2014, LaunchDarkly was valued at $3 billion as of August 2021. The company currently has 3,000 customers, including 22 of the Fortune 100.

Finding an idea

Edith had been an engineer at several startups and kept seeing the same problem over and over again with releases: developers would push a new release out to everybody and it would go horribly wrong. The company she was working for at the time had a basic system that didn’t get much attention or love. She knew that large companies had systems like this internally—Dropbox had Gandalf and Facebook had Gatekeeper—and that most companies wanted a system like those but didn’t want to have to build it from scratch.

She had the idea to build a system where you could stage releases and push them to different people (the “dark launch”). After launch, you could also have different functionality for different users. She felt a deep conviction around how feature flagging could unlock an entirely new way to develop software.

Validating the idea

Edith partnered with John Kodumal, a college friend who had been at Atlassian (which also had an internal solution to the problem). He started building a solution while Edith began talking to people to convince them to use it. Their first users were their old engineering buddies, including their first customer WidgetBox. Many of those users later admitted that the reason they tried the product initially was just as a favor to Edith!

The first organic customers came in via SEO. In 2015, Edith started blogging around feature flagging and feature management as a way to create inbound leads. She had done marketing and product in the past and knew there wasn’t a lot of good content around feature management, so new content could rank well quickly. As an additional boost for SEO, she made a point to interview leaders at prominent companies like Facebook and Netflix to create content with titles like “Secrets of How Facebook Ships.”

Finding traction

LaunchDarkly was an incredibly hard sell at first. Edith had thought it would be a self-serve business and that the value of feature flagging, staged rollouts, and the cloud were common knowledge. Instead, sales were much more hands-on than anticipated and required convincing people that this was how they should build software. She and John had to go to potential customers’ offices and sit with them to provide education. Because LaunchDarkly was a new product and small team, she knew it represented a risky sale.

“If people had any alternative besides us, they’d probably do it. We had to convince people to trust us.” —Edith Harbaugh

In the first eight months of selling, they got only one paying customer each month. “Those days were pretty depressing,” said Edith. “We tried to look for the bright spot that we had at least one customer a month, and got really excited when somebody signed up on the website, sight unseen without a phone call.” She found encouragement in a support call they did with InVision, an early customer: the call was on Zoom (much less common seven years ago than it is today), and suddenly more than a dozen employee faces popped up on screen. That showed her that people were invested in LaunchDarkly and using it enough to care about asking questions.

They raised a seed round in 2015 but struggled to put together a Series A because VCs doubted that the market was big enough and that developers would pay for it. Instead, Edith got more customers and was on a path to become profitable. “Revenue is its own series A,” as she put it. In 2016, they signed their first six-figure contract, which felt amazing because VCs had previously told them it was a $5 per month developer tool. That six-figure customer paid by check, and Edith took a picture and sent a copy of the stub to those skeptical VCs.

The growing sales had a snowball effect as current customers became references for new customers, and the business took off. While Edith was convinced her idea was sound from the beginning, she acknowledges it took a lot longer to get going than expected. “I remembered Jason Lemkin saying SaaS businesses would take two years,” she said. “But the customers that started using LaunchDarkly stuck with it—we had very low churn. I knew that it changed the way software was built for the better.”

When LaunchDarkly was a huge success years later, her former boss remarked, “Edith, you built the system you always wanted.”

💡 Moment: Strong internal conviction from seeing this problem at previous companies carried Edith a long way, before eventually getting external validation from the inbound responses to the LaunchDarkly blog, the InVision call showing high employee interest, and landing their first six-figure deal.

What advice would you give a founder just starting out?

“Build something you’re excited and passionate about but with a market that is more than just you. If you’re not excited about the work, it shows.”

Quick tips:

You can educate the market on the value of your product, but be prepared for a longer road.

Your earliest users should feel the pain you’re solving very, very deeply.

If you can’t raise funding, you can also grow revenue as a way to fund your business.

Understand why your potential customers might say no, and work to help them overcome those objections.

Deep conviction in the value of your solution can help you weather the harder times.

Kurtis Lin is the CEO and co-founder of Pinwheel, the market-leading payroll data connectivity platform building the income layer to power a fairer financial system. Pinwheel has raised $77M to date, built a team of 100+, scaled its platform to 4.6M monthly transactions, and signed flagship customers like Square, Varo, Current, and many more.

Finding an idea

Kurt and his co-founders, Curtis Lee and Anish Basu, went through multiple early pivots in their founder journey and, along the way, built a framework for developing ideas, researching them, rating them on 32 different attributes, and stack-ranking them. The framework covered everything from TAM to potential regulations and natural acquirers—all elements he considered critical to building a winning business. Kurt had 20 ideas on the list before choosing the number-one idea, which eventually became Pinwheel.

They started with health savings accounts (HSA), because Kurt and Curtis had both had poor experiences using them and recognized that many Americans living paycheck to paycheck lacked the cash flow to pre-fund their HSA. They considered building a way to invert the process and let consumers make health purchases on their Plaid-connected cards and then credit tax savings onto paychecks. They tested an algorithm to scan customer card transactions, flag them as medical expenses, and credit the tax savings back via employer payroll systems but ran into challenges around the volume of integrations needed because every potential customer immediately asked, “Do you support [Gusto, ADP, Workday, etc.] payroll system?”

Instead of building their product, they were spending all of their engineering hours building integrations into payroll systems, which led Kurt to wonder, If these integrations are this big of a problem for us, maybe they are also a big problem for other people. They built a lead list by identifying an ideal customer profile (ICP) and checking market maps and competitive analyses to find others who would ostensibly have the same needs, and then started talking to people. The moment Kurt and Curtis mentioned how difficult it was to access income and employment data, the tone of the conversation would change and people’s eyes would start lighting up. By the 12th or 13th conversation, it was clear the problem they were experiencing was quite common.

Validating the idea

At that point, they considered the TAM around who needs income/employment data to power their products and realized there was a real opportunity to focus on the infrastructure layer to help others build the products they wanted to build. Initially, they assumed their target customers would be digital lenders and banks. In doing user research, they heard that current solutions were too expensive, didn’t offer enough coverage, and had inaccurate or stale data. Pinwheel saw those as solvable problems if they could build API integrations and add a layer on top.

Through additional research, they developed three hypotheses:

They could provide better, cheaper, real-time data for lenders.

They could meaningfully increase direct deposits for banks.

They could extrapolate a combination of those two ideas and collect repayment out of direct deposits in a form of paycheck lending.

While each idea seemed compelling, they felt like they needed to pick one as a wedge. They’d pitch all three ideas to prospective customers—Kurt got the whole pitch down to seven minutes and even tried switching the order in which he presented to see if the response changed, but people always leaned forward on the direct-deposit part. He would get interrupted by prospective customers: “Wait, you can do what?” Direct-deposit switching was the holy grail for many of their prospective customers, because it meant having a much deeper relationship with their users. That became the wedge.

The next step was validating the implementation. They were initially worried that most people didn’t log in to payroll systems regularly and wouldn’t be able to remember their passwords (this was certainly true for themselves and their friends). But broader surveys showed that many people (especially hourly workers) log into their payroll systems much more often, with 70% to 80% logging in every day. This was another huge insight that confirmed the need for what they were building.

💡 Moment: When Kurt mentioned the idea that eventually became Pinwheel to prospective customers, they’d give a noticeably strong reaction: perking up, nodding along, or even interrupting him—“Wait, you can do what?”

Finding traction

Pinwheel came out of stealth in June 2020 after fundraising, with no PR strategy other than asking a friend at TechCrunch to write an article. They’d hoped for 20 inbound leads from that one article and instead got 133 in the first 72 hours—not just other startups but major companies like Chase, Wells Fargo, Citibank, Bank of America, PayPal, Square, SoFi, Credit Karma, and more. The combination of prospective customer feedback around the direct deposit idea, validation from the survey results, and the strong inbound reaction led them to believe “There’s really something here.”

What advice would you give a founder just starting out?

On selling to businesses:

“If you’re not decreasing cost or increasing revenue, nobody is going to buy your product.”

On trying to reach PMF

“What people never talk about is just how f*cking hard it is to actually get to product-market fit. In fact, most people never get there. Instead, all you hear about is all the breakout businesses where people magically found PMF. As Marc Andreessen said about finding PMF, ‘When you know, you know.’ Until you find it, you don’t have it. If you have to ask the question, you don’t have it. Put that as the bar you have to clear. It’s ruthless, but if you don’t look at it that way, you just won’t make it.”

Quick tips:

Create a structured way to assess your ideas and research to help you evaluate.

Talk to as many customers as possible until you discover some earned secret or insight.

Pick a single product wedge as a starting point.

Ryan Petersen is the CEO of Flexport, a full-service global freight forwarder and logistics platform using modern software to fix the user experience in global trade. Founded in 2013, Flexport has raised $2.2B to date.

Finding an idea

An entrepreneur at heart, Ryan had his first inkling around the idea that eventually became Flexport nearly 20 years ago. He was running a business with his older brother importing products from China and really feeling the pains of managing customs, regulations, shipping, and other logistical challenges. He wasn’t alone: he saw that clearing customs was really challenging for people who aren’t experts, like entrepreneurs, Amazon merchants, and small businesses. In 2008, he started to lay out some initial thoughts for a business to address this pain in an Excel sheet. He envisioned building something like TurboTax for customs that would make it understandable and easy, with an expert available to walk people through it and get them cleared.

“I wanted to be able to help a small business clear customs.”

Validating the idea

Before starting to build what he knew would be a complex platform, Ryan used Photoshop to create screenshots that looked like a real app. He put them up on a website to see if people would sign up for this fake product and used SEO and Google ads with a small budget to drive traffic to the page.

Over 300 companies signed up for Ryan’s fake company, which gave him real validation that there were at least hundreds of companies who would want this if it existed. He conducted phone interviews with people who had signed up, as well as friends who ran importing businesses, asking questions like Who do you use for customs support today? What are you paying for these services? What are your pain points? What’s annoying to you? If you could have a magic wand to make a problem go away, what would it be?

Throughout the interviews, Ryan would double-click on answers to dig deeper. He learned that people desperately wanted clarity and transparency into the customs process, their obligations throughout the process, when their cargo would be released from customs, what they would have to pay, and how to avoid customs inspections and holds.

The sign-ups on the website, the findings from exploratory interviews, and learning that large enterprise companies didn’t have their supply chains dialed in beyond emailing Microsoft Excel and PDF attachments around gave him enough conviction to start building Flexport.

💡Moment: When Saudi Aramco signed up for the mock product on the website. “I thought I was going to get Amazon merchants and small companies, but then the biggest oil producer in the world signed up for my fake website. I realized this could be much bigger: I thought it was just going to be for small businesses, but if the biggest companies in the world are saying this is a pain point, there’s something here.”

Finding traction

From 2010 to 2013, Ryan and his team worked on building v1, which included getting licensed by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security Customs and Border Protection, building the software, and meeting all of the compliance rules. While he had contractor engineers, his first employee had previously spent 25 years as a customs broker and was an expert on the process and rules. The product launched at the beginning of 2014 with a laser focus on solving the customs problem—companies had to actually buy freight from another provider.

The sign-ups came in quickly—Ryan estimates several per hour. But many were individual, one-off customers, like the man who ordered a bouncy house from China for his kid’s birthday party or the U.C. Berkeley professor who bought a tuk-tuk in Cambodia and wanted to bring it home. There was a steady flow of demand from these types of customers, but Ryan felt it wouldn’t be enough to build a venture-scale business. When the team went to sell to companies with potential for repeat transactions and real supply chains to manage, those companies weren’t willing to sign up because they didn’t want to separate customs from freight.

Ryan and the team quickly discovered that their hypothesis around focusing solely on customs was incomplete—companies wanted to buy customs and freight bundled together. They had always planned to add freight services but had assumed they could add that several years into the roadmap after perfecting the customs product. Instead it became apparent they needed to accelerate that to interest larger customers.

That pivot to add freight made the business much harder to build but also more defensible and valuable. The team opted to focus on a broader product surface area, offering an end-to-end solution that was more appealing to customers. It stretched the team and challenged traditional product narratives around perfecting narrow areas of focus, but Ryan believes it ultimately made them better and made it much harder for new entrants to build competing businesses.

Their first big freight customer was one of the world’s largest watchmakers: the company liked the promise of the Flexport platform but only wanted to sign up if it could get a specific price on freight. That price was half of what Flexport was paying for freight at that time, so the team had to hustle to set up enough business to lower their freight price to meet the watch company’s demand. It worked, and Flexport signed their biggest deal yet to ship 200 containers for the company.

“It was very, very obvious at Flexport that we had product-market fit as soon as we moved into freight. We had trouble keeping up with the demand and had to learn as fast as we could how to do it, how to build systems for it, and how to be more efficient at it.” —Ryan Peterson

In 2014, Flexport joined Y Combinator, partnered with First Round, and earned $2M in revenue. They learned how to do enterprise sales to the biggest companies in the world while still maintaining a focus on serving SMBs and Amazon merchants. “There were no silver bullets here—instead there have been a lot of lead bullets and steady improvements to the way we work,” Ryan says. Once Flexport offered the full package of customs and freight, its revenue shot up quickly, growing by 4-5x per year (from $2M to $10M to $50M in just the first few years). Now, eight years later, the company is on track to do $5B in revenue this year and is the fourth-largest U.S. freight forwarder by volume operating on the world’s largest trade lane, the trans-Pacific eastbound.

What advice would you give a founder just starting out?

On deciding to be a founder:

“If you’re doing it to learn, then you kind of can’t lose. If you’re doing it just to make money, on a risk-adjusted returns basis and accounting for the possibility of failure, founding a company is not the best way to make money, and you’ll ironically probably make less money.”

On getting started:

“A lot of people think that if they can’t raise venture capital, they shouldn’t do a startup. But I think you should pick something you can do, get started, and try to get traction before raising. I had student debt when I started one of my early businesses and I took side gigs to make money to pay that off while having the flexibility to work on my business.”

On confidence:

“Don’t be too sure of yourself. You have to be adaptable and open to the idea that you could be wrong and that there could be other ideas that are better than the one you have.”

On finding product-market fit:

“If you have to ask the question of whether you have PMF, then you don’t. It’s really obvious if you have it. If you can’t keep up with the customers and their demands, you have it. If you’re taking orders from internal management instead of external customers, you don’t have it. That’s fine, but don’t hire too many people, and keep your burn rate low.”

On finding focus:

“Spend your time figuring out which customers you’re going to listen to and prioritize, because you can’t help all of them.”

Quick tips:

Find low-lift ways like landing pages with mock product screenshots to validate your idea with real customers before starting to build.

Assess your early customers to understand their needs, and use that information to make product decisions that align to your business goals.

Consider taking on income-generating side projects in the earliest days of building your company so you have time to build but money to live.

What traps should I look out for?

No matter which method you use to validate a company idea, you’ll find no shortage of challenges. Here are six common traps:

Trap #1: Asking the wrong questions. It seems really easy to just start talking to people, but if you don’t approach customer conversations correctly, there’s a good chance you’ll come away with useless or misleading information. Humans don’t see themselves clearly and are often bad at predicting their future behavior, so instead ask people about their past and current actions and problems. This will lead you to facts versus guesses and opinions. For example, instead of “Would you want to solve XYZ problem?” ask “How have you tried to solve XYZ problem in the past?” If the person tells you they’ve never looked for a solution to that problem, chances are good you won’t be selling them one. For more on this, check out the great book The Mom Test.

Trap #2: Settling for a “meh” or “nice to have” reaction from early customer discovery. As an early-stage investor, this is the trap I see founders fall into most often. Remember that people are generally trying to be nice, so if you ask them if your new product would help them, they’ll probably say, “Sure, yeah, I’d check it out.” Successful founders didn’t settle for lukewarm reactions. They kept searching for a big problem and a solution that was literally being pulled out of their hands, even in the earliest, roughest version. Cocoon started by exploring ideas around financial planning and heard lukewarm reactions—but when they hit on parental leave, people pounced on the topic. You’re looking for that kind of energy.

Trap #3: Not having enough conversations. It’s critical to talk to people in your market to hear about their experiences, needs, and frustrations firsthand. You should start having conversations from the moment you’re thinking of starting your business and not stop until you sell the company or close the doors permanently. Customers (potential, current, or past) are the best source of information on your company and product. There’s no one right answer for how many people you should talk to before starting to build your product because it really depends on what you’re building and who you’re targeting. In general, you want to keep starting new conversations until clear patterns and themes begin to emerge. For Good Dog, around 20 dog owners felt sufficient, since customers across different demographics mostly still find dogs the same way. But for B2B products, I prefer to see a higher number (like 50 or more), since different businesses have very different buying patterns. The founders of Cocoon talked to well over 50 people just during the early research phase! After you start building, keep conversations going to continually validate what you’re doing—feedback is your best tool.

Trap #4: Selling a vitamin, not a painkiller. Painkillers are “need to haves”—if you have a headache, you’ll go out of your way to get an aspirin. Vitamins are “nice to have”—you’ll take them if you remember or have them handy, but they’re not a necessity. You want to build something people need right now and are willing to give you their time or money to get. Some classic “painkiller” products include UberX, Google search, and Mailchimp, while you might recall notable “vitamins” like Google Glass, Crystal Pepsi, and CNN+.

Trap #5: Myopia in focus (e.g. only focusing on the product). Having a great idea that people want is essential, but so is having a great way to get that idea out to the market. You need to be thinking about both along the way or your business won’t take off. You don’t need a go-to-market or growth strategy on day 1, but you need to have a few smart hypotheses for how you’ll find and win customers.

Trap #6: Pivoting too early. It takes a long time and a lot of work to test an idea and give it time to develop. Don’t rush to throw in the towel and find a new idea too soon. There’s no right answer on timing, but expect to spend at least a month or two digging deeply enough into an idea to explore it fully and up to a year or more to bring it to life in the market.

Trap #7: Pivoting too late. It’s also critical to not spend too long on an idea that isn’t going anywhere. Find an idea, figure out how to validate it, assess the results you’re seeing, and be ready to change course if you’re not feeling a strong pull.

How do you know if it’s too early or too late? Unfortunately, there’s no magic formula. It’s too early if you truly believe you’ve found a real pain point and just can’t seem to nail the product execution or GTM. It’s too late if you’re out of money or sanity, or if no one seems to want what you’re building after multiple tries from various angles. Everything in between is a gray area.

What do I do once I’ve gotten some validation that this idea can win?

Celebrate ;) That seems trite, but I often hear founders say they wished they’d taken more time to enjoy the interim victories, however small, instead of always grinding on to the next step. This becomes especially important once you have a team that needs to feel like their hard work is producing progress worth acknowledging. Edith from LaunchDarkly shared how she leads her team: “Each day, we talk about what we did yesterday. Then we discuss what we’re going to do today. It keeps a one- or two-year project from feeling daunting. I also find that it creates a great deal of pride and accountability.”

Beyond taking time to appreciate the small and large wins, there are steps the most successful founders take once they’re feeling real market pull for their solution and seeing traction:

Document your metrics and share them with your investors and advisors so they know you’re making progress and are prepared to help you with next steps.

Keep updating your roadmap and goals so your team knows where to focus their efforts and how to plan for and create continued growth.

Carefully expand your team while making a conscious effort to build the company culture you want, all while keeping an eye on your burn rate and cash reserves.

I’d love to give you tidy answers on when to raise various rounds of funding, but it’s not an exact science and there’s no one set of metrics to achieve for each raise. For general guidance, you should check out Lenny’s recent article on good growth rates based on conversations with 25 investors. As an investor now, I’m looking for a smart, motivated founding team taking on an interesting market with a solution they believe can win. How they demonstrate that from the idea phase up through raising later rounds depends on the company and how success is defined in that business.

Final thoughts

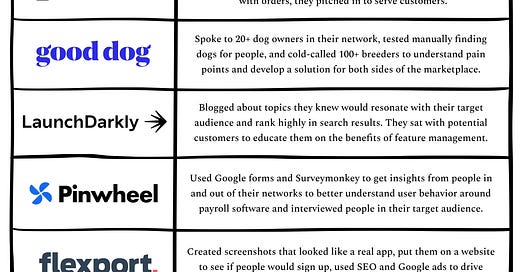

Founding a company sounds glamorous and exciting, and if all goes well, it can be—eventually. But the road there is filled with a lot of steps that can feel awkward, tedious, or downright discouraging. I’m not going to lie and say I loved meeting strangers on Craigslist to ask them about their Android points. Every founder I talked to shared stories of doing hard things on the way to validating their ideas. Here’s a quick review of the steps they took:

All of these tactics helped the founders better understand their audience and gave them the confidence they needed to keep building. I loved hearing these stories because it confirmed that all of these successful companies were started by people who were willing to put in the gritty work to develop and test their ideas over and over. I’ve noticed that after conducting all these interviews, when I hear new pitches myself recently, I’ve become especially mindful of learning the ways that founders discovered and validated a burning need for what they’re building.

The early journey as a founder really comes down to a few steps, regardless of what kind of business you’re creating:

Find an audience with a problem they want solved.

Have the empathy and creativity to come up with a solution that resonates.

Put in the work to validate the solution with your target customers.

Make sure there’s a large enough audience who wants to buy what you’re selling.

Find clever ways to reach that audience. Be willing to do things that don’t scale in the early days, but look for non-linear ways to scale as you go.

There’s still a lot of timing and luck involved, but following those steps will create the conditions for success. First Round meets with dozens of early-stage founders each week, and we look for founders who will take the time to move through these steps. It’s not always a linear path, and every business is different, but the best founders take the time to search out a big problem worth solving and pair it with an earned insight on the right solution. If you’re that kind of founder, I’d absolutely love to meet you and hear what you’re building.

You can email Todd at todd.jackson@firstround.com, and follow him on Twitter and LinkedIn.

Have a fulfilling and productive week 🙏

📣 Join Lenny’s Talent Collective 📣

If you’re hiring, join Lenny’s Talent Collective to start getting bi-monthly drops of world-class hand-curated product and growth people who are open to new opportunities.

If you’re looking for a new gig, join to get personalized opportunities from hand-selected companies. You can join publicly or anonymously, and leave anytime.

🔥 Featured job openings

Roofstock: Senior Product Manager (Remote)

Clipboard Health: Growth Strategy and Marketing Manager (Remote)

Around: Product Manager (Remote)

Karate Combat: Founding Product Manager (Remote)

Balance Homes: Founding Product Manager (Remote)

Ellis: Software Engineer (Remote)

WorkWhile: Head of Product (Remote)

Clipboard Health: Engineering Manager (Remote)

If you’re finding this newsletter valuable, consider sharing it with friends, or subscribing if you haven’t already.

Sincerely,

Lenny 👋

Just outstanding. If anyone you ever know says they "have an idea" or they want to start a company - send them this

This article is a gem. Seriously. Great work, Lenny