👋 Hey, Lenny here! Welcome to the ✨ monthly free edition ✨ of my weekly newsletter. Each week I tackle reader questions about building product, driving growth, working with humans, and anything else that’s stressing you out about work. If you’re not a subscriber, here’s what you missed this month:

I recently learned that Facebook Marketplace is the world’s second-largest marketplace, in terms of monthly active users, behind only Amazon. It’s ahead of Alibaba, Walmart, eBay, Taobao, and has quietly left the once-unconquerable Craigslist in the dust. For years, I’ve been curious to learn what it took to make Facebook Marketplace work, when so many local marketplaces (including Facebook’s previous attempts) have failed. There is no better human alive to tell this story than Deb Liu, and below, for the first time, Deb shares the story behind Facebook Marketplace.

Deb led the team that pitched, built, launched, and scaled Facebook Marketplace from just an idea to what it is today. During her 11 years at Facebook/Meta, she also led teams that built Facebook Login, Facebook Pay, Facebook Commerce Manager, and dozens of other foundational Facebook products. Deb left Facebook about a year ago and is now the CEO of Ancestry. She also sits on the board of Intuit and is the author of the soon-to-be-released book Take Back Your Power: 10 New Rules for Women at Work (I’ve already pre-ordered it and so should you). To learn more from Deb, definitely subscribe to her newsletter, and follow her on LinkedIn. Enjoy!

I pitched the idea for Facebook Marketplace in 2009, when Sheryl Sandberg interviewed me for a Product Marketing role at Facebook (aka Meta). We didn’t start working on Marketplace until 2015, however. Five years after launch, the Marketplace Tab on Facebook now has over a billion monthly active users, more than Snapchat and Twitter combined. The story behind it is well-known within the company but has rarely been publicly documented in detail . . . until now.

The early days

I knew I wanted to build commerce into Facebook from the moment I walked into my first interview. It seemed inevitable that social commerce would be an important part of the company and its products. Social networking was not simply about sharing with friends; in many places, especially in emerging markets, commerce was a core part of the “jobs to be done” on Facebook. In fact, in many early research studies, more than half of people studied in many countries cited Facebook as a place they had bought or sold things. This was less common in Western markets, which made it a blind spot for many of those at the company.

Unfortunately, I was terrible at selling the idea, and for five years, nothing happened. We tried hackathons, enlisting interns, and testing new products (Wishlist, I’m looking at you), but we never quite built up the momentum to get it going. This was in part because of previous failed commerce attempts, like Beacon and Oodle, but also because the idea of selling something on Facebook seemed strange to many of the employees.

But I saw something they didn’t. In 2012, I was the only PM who was a mom. I used to joke that because I had three kids, and there were six women PMs, on average we each had half a kid—but I had to go home and take care of all of them. I was a member of multiple mom groups, where people bought and sold all sorts of things. Kids generate a lot of used goods, many of which are insanely expensive to buy new. I also had friends in Asia who talked about how meaningful buying and selling in groups was to them, and how Facebook was the place to connect for commerce. This put me in a unique position and allowed me to see what others in the company couldn’t. Although the efforts didn’t take for several years, I continued to toy with the idea and brainstorm ways of making it possible.

The testing

One day, a rotational product manager, Bowen Pan, joined Facebook and said he wanted to work on enabling commerce within Facebook groups. He had previously worked on TradeMe in New Zealand and saw what Facebook could do. Vijaye Raji, our engineering lead, immediately pulled a couple of engineers from our team, and we started testing a product we called Groups Commerce.

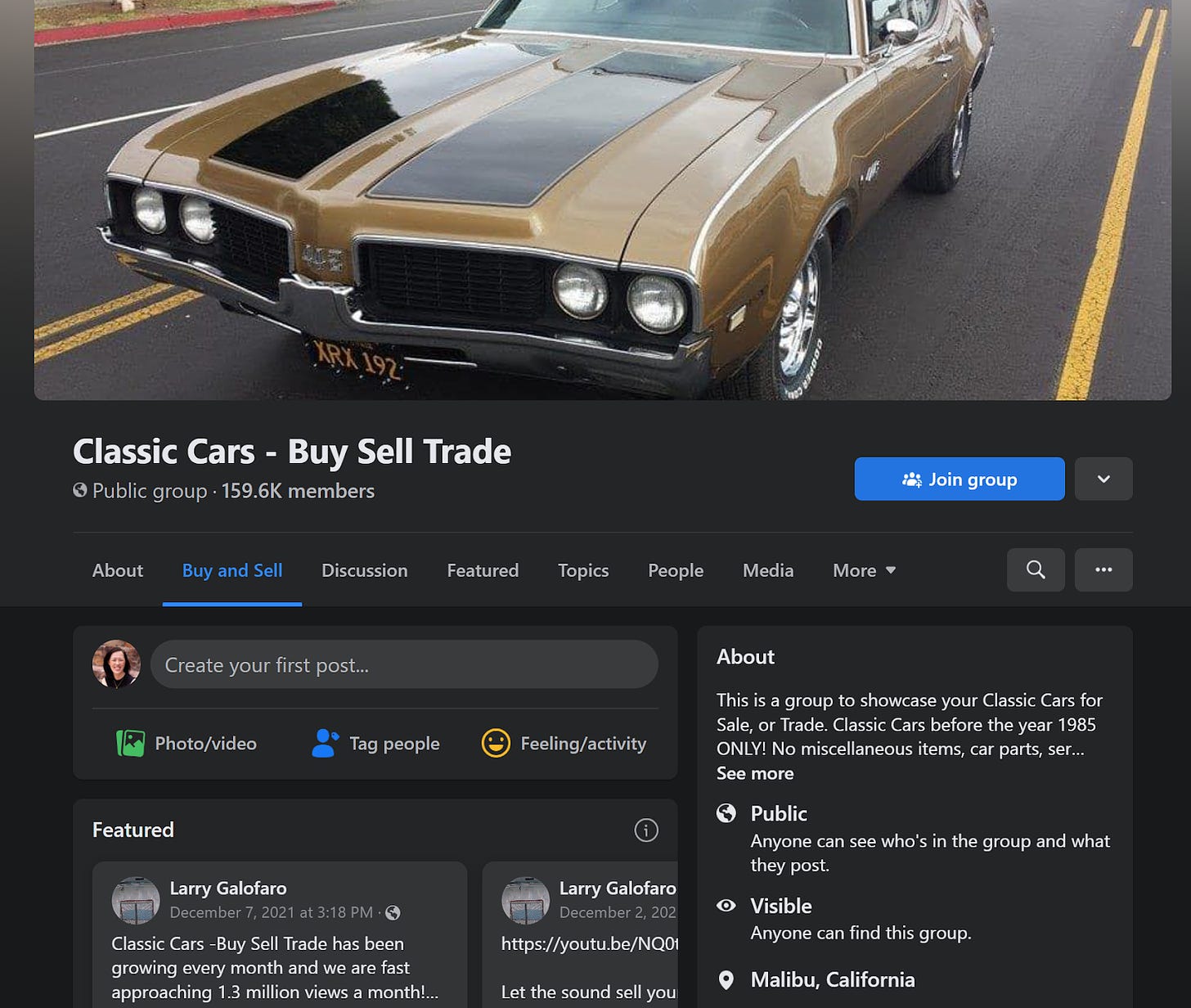

At the time, commerce in groups was informal and completely organic. One of the biggest issues early on was that there was no way to know what groups were meant for selling things (vs. being purely social). We decided to set up a way to allow group admins to opt into becoming classified commerce groups. This allowed us to track organic behaviors on the platform. We found that many more people were part of Facebook Groups communities that had been set up specifically for buying, selling, and trading than we expected. Some were local mini-marketplaces (ex: Denton Buy and Sale), some were interest groups (ex: marble collectors trading), and some were both (ex: classic car sale groups). Some of our earliest experiments were simply structuring the groups so that items for sale showed up as listings rather than just discussion posts. We also started to rank the group content to help people discover products for sale. Prior to this, no group content was ranked—it was purely chronological.

We eventually ran into a problem. Being stuck within the Groups system was constraining, and most users had trouble discovering groups, joining them, and finding items. This meant that we faced the twin marketplace issues of limited seller liquidity and difficult buyer discovery. Buyers told us in research studies that they couldn’t find the items they wanted, and sellers felt that their reach was limited. We knew we had to think bigger.

The pivot

Almost every two-sided marketplace struggles with bringing on enough supply and/or bringing on enough demand. Surprisingly, Facebook didn’t. We already had both buyers and sellers, but we weren’t succeeding in making the connection between the two. As long as we stayed within Groups, we could not address this issue. We had two options:

Add a tab within the app

Launch a separate app

We debated for some time and finally decided that having a tab in the largest app in the world was preferable to having a separate app. The ability to work within the Facebook ecosystem, where millions of people were already trading in communities, made this decision a no-brainer. Though we expected to launch a separate app once Marketplace became successful, you will likely notice that it never happened in the years since, because the experience was better integrated into Facebook itself.

Launching one of the first new tabs in the app was no small feat. The good news was that Mark [Zuckerberg] wanted to make space for more “jobs to be done” in the app by adding new tabs. He offered the opportunity to our team and the Video team first. As other teams began requesting tabs, including Groups, Pages, and News, the team that managed the navigation within the app had to create rules about how tabs could be used and how the channels could be leveraged. This led to the development of the system of dynamic tabs you see today.

We evaluated a number of options for building the V1, balancing speed and functionality, and decided to use React Native, one of the first major products to do so. This enabled us to build nearly twice as fast, at the cost of flexibility. Under Vijaye’s leadership, the coding and launching of our V1 product to several U.S. cities took about two months.

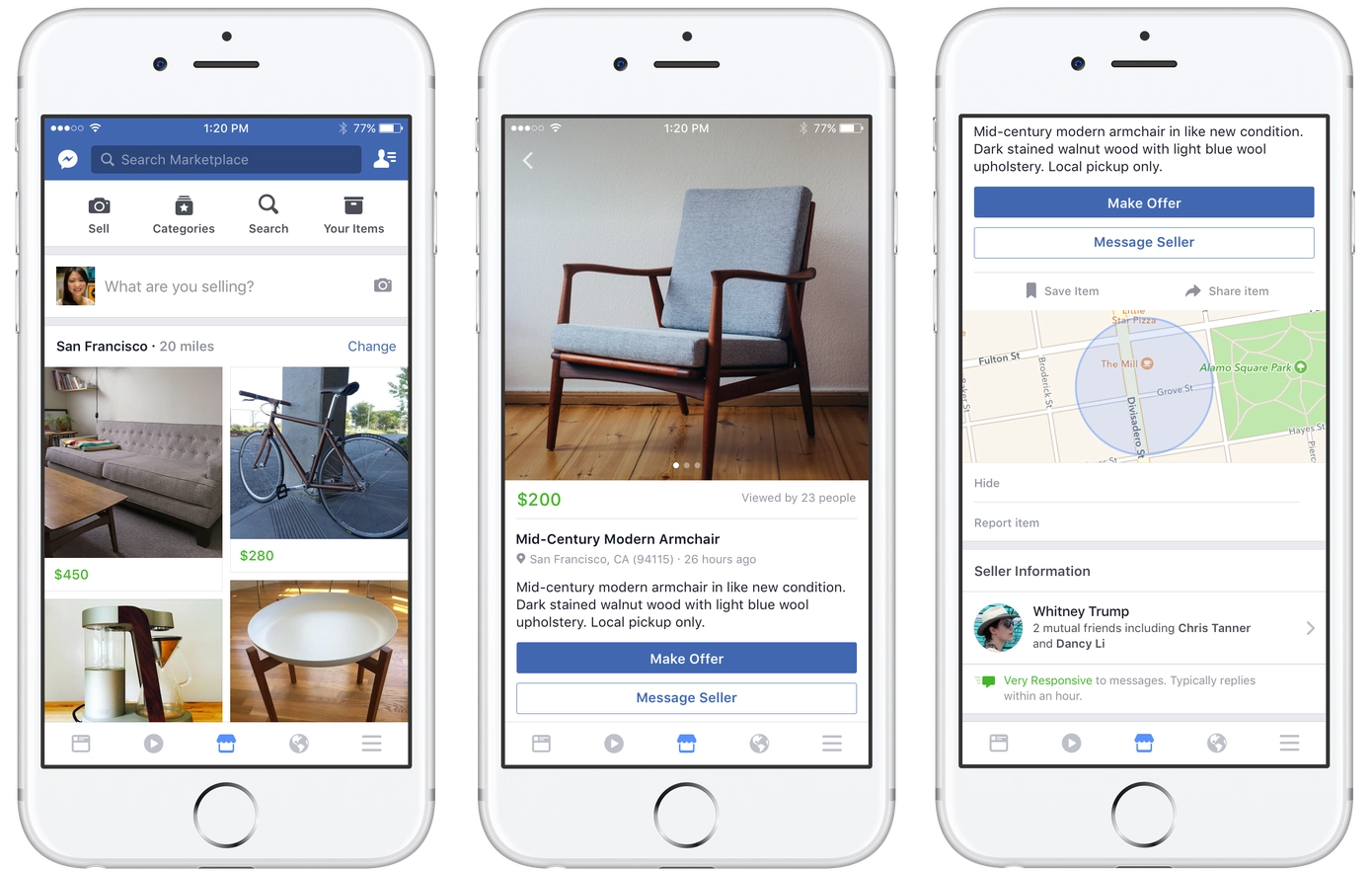

Once we had the tab within the Facebook app to drive buyer engagement, we settled on the key metric of weekly buyer retention. Our early bet was that supply would drive demand—that having sufficient inventory would get buyers excited about coming to this new tab to browse. To do that, we had to get sellers on board. Sellers had no incentive to create new listings on an unknown marketplace with no clear buyer engagement. That led us to make it a “one-checkbox experience,” which allowed sellers to take items that were already being listed in groups and cross-post them into the Marketplace Tab as a way to seed the early supply.

Some items were more suited to Groups, such as marbles, which were mostly bought and sold by enthusiasts within their own communities. However, many sellers wanted to drive maximum discovery to move items, especially larger ones, like furniture, cars, and electronics. As we tested cross-posting, we were able to assess the quality and diversity of the inventory that would show up in the new Marketplace Tab well before launch. Typically, we turned on cross-posting within Groups for two months before we rolled out Marketplace in that area.

Surprisingly, buyer engagement among weekly active users was relatively high at the start, and it remained so during the testing period. This meant that we were able to keep buyers coming back on a regular basis. Once we had sufficient buyer engagement, we decided to roll out from a few cities to a few states. Before long, we were ready to launch in five countries, which we selected carefully to ensure that we got a sense of the product’s performance in different areas of the world. We were no longer going to be in beta, but were ready to go live on a broad scale.

The launch

The launch of Marketplace happened on October 4, 2016. This was the New York Times headline heralding the rollout of a product we had been working on for a year and a half, a product I had dreamt of for seven years:

Needless to say, it wasn’t pretty. A small bug in the fraud queues resulted in a massive flood of violating items. We were able to get it cleaned up quickly by reinstating the rules, but it was an inauspicious start, to say the least. But this was the first in many lessons about what could—and did—go wrong on the path to success.

How we made Marketplace work

1. Focusing on trust

Buying and selling face-to-face meant that trust was a huge factor, especially when it came to bulky items that required people to meet up in person. We sold our minivan on Marketplace, and we knew we had to meet with buyers. My husband reviewed the profiles of everyone who messaged him and arranged a meetup with the first two people who reached out. He felt more comfortable seeing their real identities and the duration they had been on the Facebook platform, something that wasn’t possible on other, anonymous platforms. He invited them to meet him near our home to test-drive the vehicle. Within 48 hours, he sold the minivan to a small-business owner, who paid him in cash, and they went to transfer the title together.

2. Engaging Facebook active users

People use Facebook widely and frequently, often multiple times a day. Adding a local and shipped commerce solution only extended the value of the app and the things that could be done with it. The fact that you can have the app open already and see when something new comes up for sale is part of the serendipitous discovery aspect of Marketplace.

3. Integrating with Messenger

Being integrated with Facebook Messenger makes communication fast and easy. It allows you to pin your location and have someone come to you, or easily send a deposit to someone. This has greatly streamlined the buying and selling process.

4. Leveraging the Groups community

I am a member of a Buy Nothing group, and I also regularly buy and sell on Marketplace. I bought an entire bedroom set from someone moving down the street, who turned out to be a friend of a friend. I bought my kids two digital cameras from a student I had met at Stanford just the year before. This idea of people-powered commerce, buying from your neighbors, and reducing waste was part of the ethos of the product from the start.

Lessons learned

1. Follow the data

From the start, we noticed that some of the most popular items on Marketplace were cars and rentals, which surprised us. We did not realize that there was such demand for these big-ticket items online. We started working on structuring posts so that people could easily list places for rent and cars for sale. This enabled us to double down on these new verticals, which helped us become key players in those markets.

Notably, the “job to be done” in these categories was unique to Facebook. Many rentals were for roommate situations or home-sharing, so trust was incredibly important. Knowing someone had mutual friends or had been active on Facebook for over a decade provided confidence to those who were looking for someone to live with. The same goes for car selling: Trust is important, since you are meeting and getting into a car with a stranger. Buying a car is one of the biggest transactions someone does in a year, so taking the anonymity out of the process created a winning category.

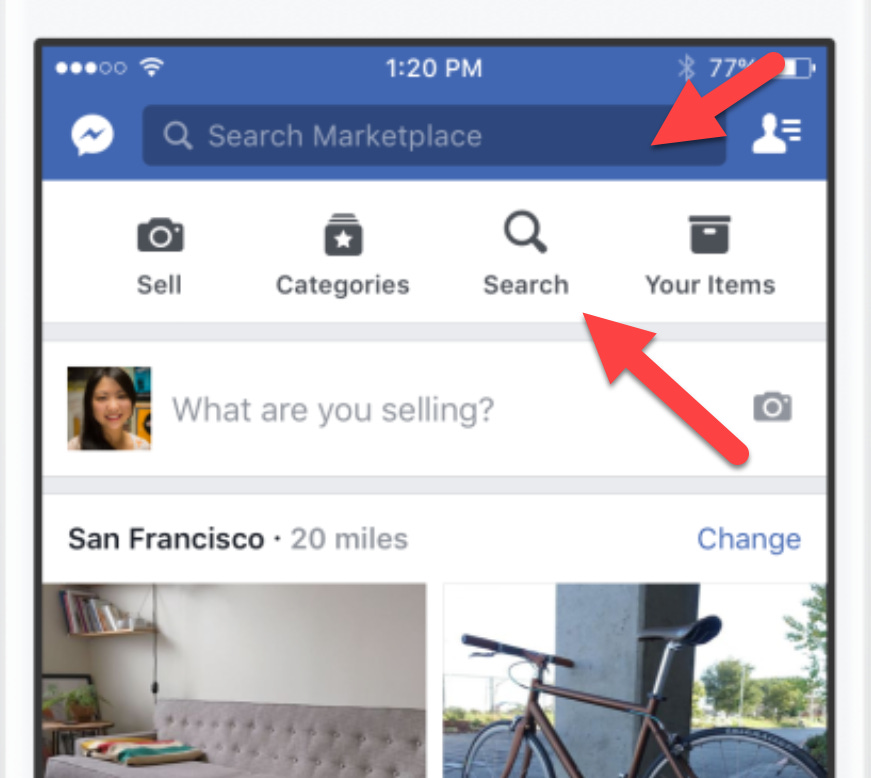

Immediately upon launch, we also noticed that search numbers were incredibly low. Our Research team showed buyers two test phones: one with Marketplace and one with a different local classifieds service. They then asked them to “find an iPhone to buy.” On Facebook, users immediately started to scroll, whereas on other apps, they searched. This led us to realize that people on Facebook had learned never to use the search bar except when searching for people. We addressed this by putting a large search button next to the search bar, which our designers grudgingly allowed. This changed the trajectory of the search participation rate, and even when we removed the button, searches remained at the new, higher level.

Following the data, we were able to iterate and evolve the product to be what users were looking for.

2. Device matters

While the product started primarily for mobile, we realized that to be competitive, we needed to add a desktop version. This was important for larger purchases and would make listing easier for high-volume sellers.

The desktop version was launched about a year and a half after the initial mobile launch in October 2016. We noticed that participation on desktop was significantly higher in high-consideration categories, such as furniture, rentals, and motor vehicles, where people liked to comparison-shop in different tabs.

In addition to the desktop version, some countries primarily relied on Facebook Lite, so we also had to adapt our product to ensure that it worked for those users. As we launched on new platforms like desktop, Facebook Lite, and mobile web, we saw an increase in engagement and transactions.

3. Navigating scaling

Once we had expanded beyond five countries, we began to notice new issues that hadn’t appeared when we were in testing in just a few states. For example, it was very difficult to distinguish between authentic and inauthentic goods. We ended up having to work with brands and build models to detect violating items. We also needed a more fine-tuned violation reporting flow and a more robust takedown and appeal process. As with any enforcement model, we faced false positives. We needed to scale the tooling to be able to perform a manual review of the sellers and ensure that they were following the rules.

We saw different problems arise in different countries, which complicated things. In one country, the issue of selling diplomas (i.e. printed certifications) appeared. This is less of an issue in other countries, so we had to decide what to do with the policy. We had to find a way to keep that particular country safe, such as detecting violations and allowing reporting of these local issues, without adding substantial hurdles in other countries where this was not a problem.

The hardest part of offline transactions was knowing when a transaction actually took place. Transaction verification was crucial; it gave us a better understanding of which items sold and which items did not, which helped us improve rankings. To address both violations and transaction measurement, we settled on encouraging buyers and sellers to report transactions by incentivizing ratings and reviews. We noted when buyers and sellers messaged back and forth to get a sense of the ways they interacted. Later, we added online payments and shipping labels with tracking information so that we could see when transactions were completed and items were delivered.

Being responsive to challenges while maintaining a core product roadmap required a team that adjusted quickly. We had to stay on top of new issues as they arose but also keep the team innovating and building features that customers expected. This is the constant push-pull of building a product that balances the needs of buyers and sellers while preventing bad actors and negotiating the external environment. Without a team that is able to flex to the right priorities at the right time, this product would never have been successful.

—

Our team often joked that Marketplace was a five-year overnight success. While it seems straightforward on the other side, there were times during that period when we struggled with achieving true product-market fit. In the end, however, we succeeded, and Marketplace is no longer the simple and scrappy product we started in 2015. It is incredibly exciting to see how far it has come, and I look forward to seeing how it continues to evolve.

Thanks, Deb! Want to read more?

🔥 Featured job openings

Otta: Product Manager (London)

Sonar: Product Manager, Integrations (ATL, Remote-US)

LiveAuctioneers: Senior Product Manager, Platform (NYC, UT)

Writer: Product Designer (SF, Remote-Global)

Shortwave: Growth Product Manager (Remote-US)

Casual: Product Designer (Remote-EU)

Browse more open roles, or add your own, at Lenny’s Job Board.

How would you rate this week's newsletter? 🤔

Legend • Great • Good • OK • Meh

If you’re finding this newsletter valuable, consider sharing it with friends, or subscribing if you haven’t already.

Sincerely,

Lenny 👋

My team writes about our weekly learning and share it in our team Slack Channel.

I wrote about my learning this week after this post and would like to share back with you as a thank-you note!

Deb Liu founded Facebook Marketplace (FM), the largest social e-Commerce platform outside China. Deb’s post has lots of highlights that are worth spotlighting, but the top ones that most resonate with me include:

- User behaviors and innovations outside the US inspire Deb to look into social commerce and form the early initiatives for FM. “Learning from NBU (Next Billing User) countries” is probably no longer news these days, but it was a pioneer thinking back in 2012.

- FM is a gigantic initiative from a historical perspective. Still, the early team started with something small — allowing FB groups to identify themselves as commerce groups, so Deb’s team can track and understand users’ organic behaviors through analysis. They understood who the users were (stores or individuals) and what they sold (from marble to car) and started to decide on experiments.

- The team experienced a significant pivot once after scalability became a bottleneck. After making a critical decision — a new tab or an app, the team focused on agreeing on a critical metric of weekly buyer retention, which is vital to guide and measure the success of this new bet.

In the end, Deb provided her top lessons learned of founding FM

- Follow the (user engagement) data to iterate and evolve the product

- Device matters — FM was mobile-first, but after observing desktop users’ significantly higher engagement in large purchases, the team focused more on the desktop version.

- Scaling was a new challenge after the initial expansion. The product experienced novel issues such as inauthentic goods, local “grey” areas, offline transactions that cannot be tracked easily by an online platform (really resonate with me with the UberEats cash transaction problem in NBUs). The team learned to be responsive to novel problems that are “branches” to the core product roadmap.

The story-telling in this post was fascinating. It was 10 minutes well-spent, and I would love to learn your key takeaways.

This story is a massive gem. The only thing that would supercharge this would be more specific numbers but I do understand sharing them may be sensitive.