Startup to exit: Lessons from a first-time founder

Why VC funding is a drug, when building in stealth is a mistake, what to do when you lose conviction, how to approach selling your company, and more

👋 Hey, Lenny here! Welcome to this month’s ✨ free edition ✨ of Lenny’s Newsletter. Each week I humbly tackle reader questions about product, growth, working with humans, and anything else that’s stressing you out about work.

If you’re not a subscriber, here’s what you missed this month:

Subscribe to get access to these posts, and every post.

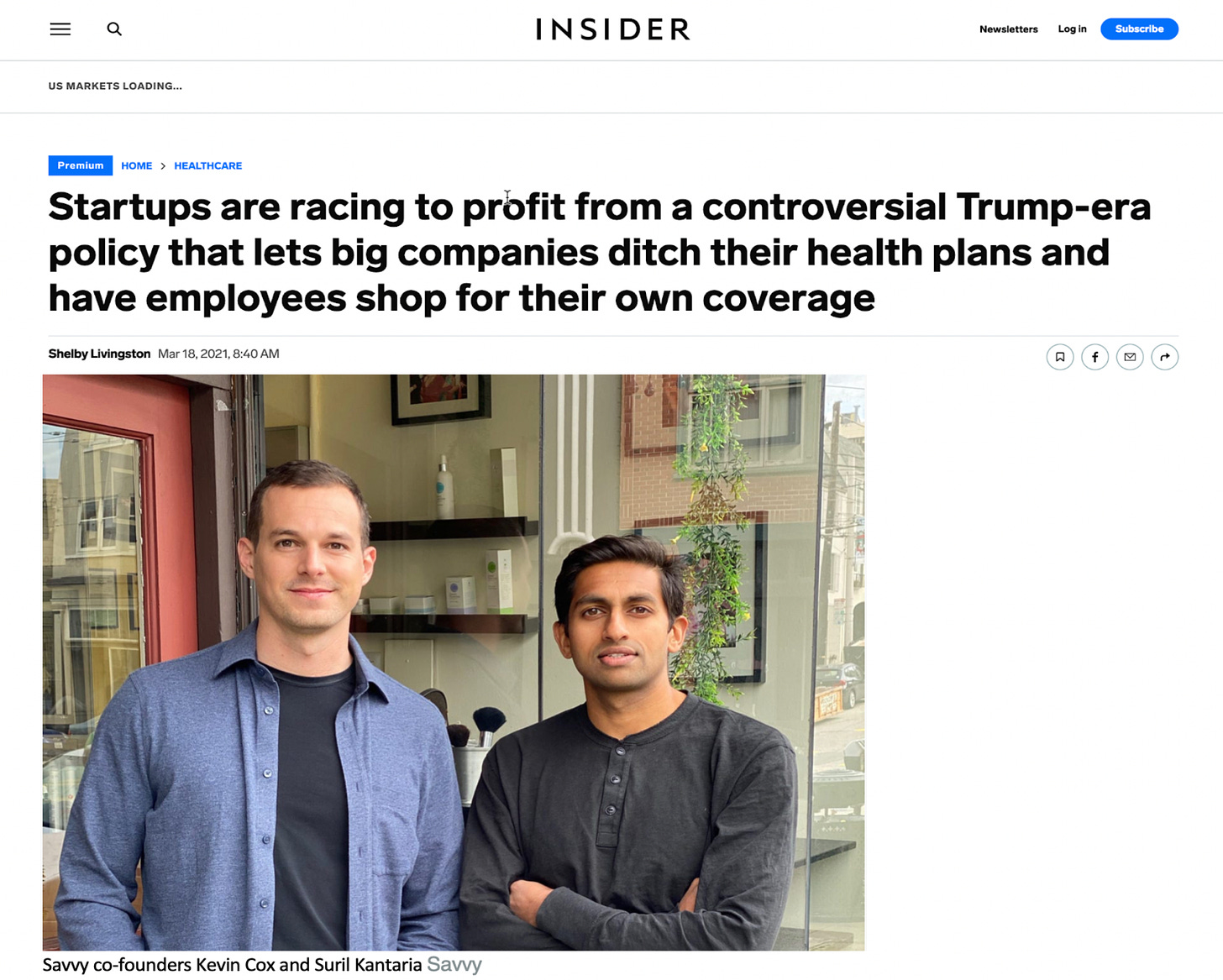

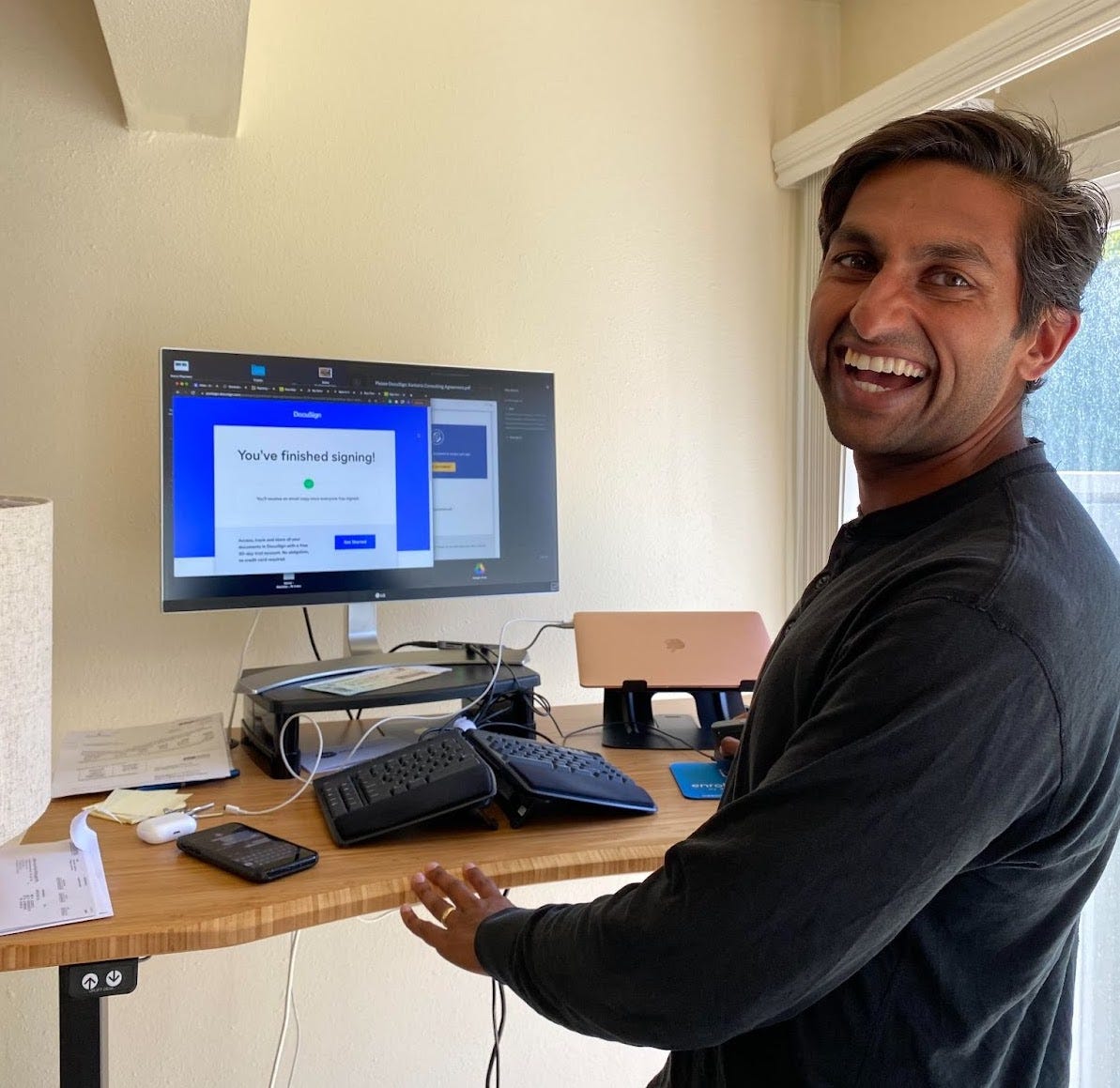

I first met

in 2020 when I was starting my life as a solo paid-newsletter person and realized I needed to figure out health insurance. Fortunately, Substack just started offering a perk called Savvy—a monthly stipend alongside a neat tool that gave me easy access to health insurance plans. Suril was the co-founder and CEO at Savvy, which in the early days meant he was my insurance advisor, enrollment specialist, and customer support—basically my personal health insurance guru. He went on to scale Savvy to tens of millions of dollars in payment volume, and earlier this year, Savvy was acquired by the leading incumbent in the market. When I caught up with Suril, he shared his startup story with me, and I found it incredibly powerful and insightful. I asked if I could share it with my newsletter audience, and I’m excited to do so below.Suril was previously the youngest-ever hire on TPG’s investment team, which led early rounds in Uber, Airbnb, Spotify, Box, and GreenSky. He’s currently advising startups on go-to-market while exploring new ideas in climate and fintech. You can connect with him on LinkedIn or Twitter.

Savvy was the first fintech platform of its kind, offering employees payment cards to buy their own health insurance. We took Savvy from 0 to 1, growing to tens of millions in payment volume across thousands of users, but sold before scaling from 1 to 100. Backed by VCs like Y Combinator and Marc Andreessen, we grew the company to a 15-person team and built the market’s first payment card technology. After three years of building, the company was acquired in June by Take Command, the leading incumbent in the health insurance HRA (“health reimbursement arrangement,” employer-funded health benefit plan) space. While our exit was not a Figma-level home run, it felt like a single to right field and the best path forward for the company.

Over the years that we built Savvy, many founders, including from the YC community, would reach out seeking advice. While I always made time for these calls, I often left feeling that I’d shortchanged my peers. There were still so many problems facing our nascent startup, how could I possibly have strong perspectives about another company’s challenges? Now that Savvy has been acquired and I’ve left the day-to-day behind, I’ve taken some time to reflect on our journey and what I wish I had known along the way. Below are the biggest lessons.

1. Don’t found a startup. Find a problem.

There’s a plethora of writing on how to identify and evaluate good startup ideas—we followed none of these.

In San Francisco in my 20s, I was in the echo chamber of Silicon Valley looking in. I had been an investor and board observer of unicorn founders and an early employee at a hypergrowth startup. This, I thought at the time, suggested that my pattern recognition was strong and, not one to sit on the bench, I was ready to build a startup.

The inspiration for Savvy came after months of research with my friend Kevin Cox on how to fix U.S. health care’s antiquated payments system. These early weeks were a slog. Fresh off quitting our jobs, we toiled from an uncomfortable dining room table, hungry to find a problem to pursue. One day while driving across SoMa, we noticed a billboard stating that the biggest industry conference in health insurance would be taking place in SF the following week.

We were giddy—we immediately scoured LinkedIn to find a way in. After many dead ends, we found our mule in a health insurance sales rep named Ari. He was energized by our hustle and invited us to shadow every meeting he had lined up at the conference. His ask in return? A couch to crash on; hotels were priced through the roof. We had ourselves a deal.

Ari shepherded us like Moses across the conference floor, stopping seemingly every 10 meters to greet an acquaintance. For us, seeing the underbelly of the industry was eye-opening and largely monochromatic—the majority of folks were 55-year-old white men in wool blazers. The “technologists” in booths were demoing what looked like my middle-school online learning software. But just a handful of chats gave us more perspective than months of online research. What’s more, we left feeling energized to grab this aging industry by its horns.

After the conference, we spent countless more caffeine-fueled hours researching the payments companies we had met. One observation was consistent: the products in the space were “old-school.” We could build a modern software offering, but what specifically to build?

We ultimately landed on the debit cards that accompany employer health plans for out-of-pocket spending. When personally using these FSA and HSA debit cards in the past, we had experienced a high-friction process that required uploading receipts on 1990s interfaces. Paired with the fact that employers are the primary payers in U.S. health care, we had conviction that we’d found the right “wedge” into modernizing health-care payments.

Without speaking to a single user, we developed a vision (and written memo) for an alternative future in health-care payments. Visions without defining a problem are dangerous. They are often solutions to made-up problems or, even worse, alternative realities to things that are working just fine.

Looking back, the lesson is clear. Good startup ideas are not about pattern recognition, modernizing, or finding wedges—they are about solving a specific problem.

In the weeks that followed, we brought our vision to prospective customers to validate the market need. At first, we received excitement and validation. However, we realized our first several “interviews” were actually sales pitches (e.g. “here’s this cool new thing, what do you think?”). Far too biased to get any real signal. After reading up on customer interview best practices, we tried again, this time with an unbiased script. Not one person brought up health debit cards as a problem they needed to solve. We concluded that our vision, which we had spent many painstaking hours developing, was off the mark. Back to the drawing board—or in our case, the dining table!

2. VC funding is my drug

VC funding is a powerful drug. You sell your vision to people with money, people who shower you with praise, people with huge Twitter followings, people who write blog posts about your greatness and once-in-a-generation ability. You feel amazing.

However, the high fades and is accompanied by amplified lows. Most people don’t talk about the pressure, the late-night investor calls, the rising expectations, the compressed timelines, the recurring fundraising circuit, and the constant external signaling.

If there were a Surgeon General warning on this drug, it might read, “Beware. VC funding may lead to dependence and complication. Some users have reported extreme anxiety, loss of control, and nightmares of being on a never-ending treadmill.”

Don’t get me wrong—venture capital can supercharge your company’s growth. And it’s often said that it’s easier to raise early, on the promise of traction, without real data to scrutinize. If you take this road, know that your company is a ticking time bomb and managing cash burn is your only defense. There will be no shortage of external pressures to spend more now and raise more later.

In March 2020, our decision to raise a seed round was influenced by being in YC. It’s just what YC startups do. The mantra was if you can raise at Demo Day, you should raise. We proceeded to line up six investor meetings per day for the next two weeks. But then came the tectonic shift. News of a deadly virus spreading globally sent the markets pummeling. We’d wake up to 3% to 4% drops in the S&P daily. We shifted all our meetings to Zoom, but investors were clearly distracted—risky seed checks were not the priority over their portfolio companies in chaos. The venture market appeared to dry up that Covid spring.

For us, it became a game—if select YC peers were closing rounds, why not us? We just needed to dig our heels in and grind, we thought at the time. Days later, San Francisco instituted shelter-in-place. My co-founder and I fled to Tahoe so we could escape lockdown and pitch from the same room. One week turned into six, but we still hadn’t found a lead investor. Our pitch that health care was on the crest of massive change and that Savvy would be first-to-market was fine, but VCs wanted to know how the business would fare in a pandemic.

It was an impossible question—no one had any idea what the pandemic would look like, let alone how any single business would perform. But we crafted a narrative: the pandemic would be an accelerant, of course! After three months of daily investor pitches from our Tahoe hideout, we closed a $2.5 million round. We were relieved, but mostly excited to go back to building and get the hell out of our cabin!

Looking back, I question why we raised when we did. We didn’t have nearly enough conviction in the business ourselves. While we had a great story for investors, our metrics weren’t compelling, with only a handful of beta customers with whom we hadn’t yet spent any time. We allowed Demo Day FOMO and fear of a market crash to drive our timing.

Why is a preemptive raise bad? For one, it’ll take longer to convince enough investors to close your round. What’s more is that by pitching investors on a vision, perhaps without realizing it you’re committing to a set path for the company. Despite a pandemic-altered landscape, we didn’t course-correct from our vision, telling ourselves “if investors backed us, we must be on the right path.” This vote of confidence from investors ultimately delayed us from seeing the truth—the market had shifted and we needed to pivot.

Not too long after our fund-raise, investors began asking us, “When is Savvy going to raise a Series A?” and “Why aren’t you hiring faster?” They would point to peer startups with ballooning headcount on LinkedIn. Some were even raising more capital just months after their last round. We had to constantly remind ourselves to ignore these extrinsic signals. As founders, we were the only people in the trenches digging for signs of product-market fit. Finding PMF should be the only input driving the decision to increase cash burn.

David Hsu, the founder of the low-code unicorn Retool, shared with me that he kept Retool’s team to only the co-founders for a full year after his seed fund-raise. His logic? A nimble team can pivot quickly until achieving PMF. What’s most important in the early days is that you spend slowly until you find traction and have reason to pour gasoline on sales and product.

One final cautionary tale. In the early days, our friends and investors would often congratulate us on each new hire. Absent other signs of traction, growing the team seemed impressive from the outside. Accepting these accolades was a mistake. Headcount is a cost center that requires precious time to grow and manage.1 The only metric that merits congratulations is product traction/PMF. Fight the urge to use vanity metrics (like team size or news mentions) as a sign of progress.

3. In public we trust

There’s something sexy about the title “founder of stealth startup” on LinkedIn. It’s mysterious and entices visitors to go deeper into your profile. You’re part of a secret club of 9,000 other stealthy builders.

Allure aside, I’ve since learned that building in stealth is always a mistake. I’ve been part of a stealthy but now successful AI startup, and I’ve observed several stealthy founding teams. One observation was consistent: stealthiness inhibits frequent market signal and greatly increases time to PMF. Any perceived gains of building an advantage over competitors by being stealthy are lost when you inevitably take longer to achieve PMF. For companies building new markets, like Savvy, competitors may even be valuable in evangelizing the new market. If a rising tide lifts all boats, you want the tide to rise faster!

I’d take a completely opposite tack—be a public startup. As the VC Bill Gurley said to us, you should “shout from every rooftop, tell whomever will listen.” Startups don’t win because their idea is original. In fact, in the early days, many people will think your idea is dumb (which doesn’t matter, because these people are not your customers). Startups win because of hard-earned execution. Building in public invites attention from all sorts of prospects: customers, employees, and even investors. All these inbounds may not be useful, but from my experience, a subset are typically accelerants for your business.

In the early days at Savvy, our inclination was to build quietly. It was easy to justify—we were in a new market with a perceived first-mover advantage. We weren’t ready for the spotlight, and competitors would surely steal from our A+ product and marketing. Despite YC’s urging, we delayed a public launch, blog posts, or LinkedIn posts. In doing so, we inadvertently delayed sales inbounds from customers, an understanding of the segments most in need of our product, and market feedback. When speed is your only advantage as a startup, the costs of building in stealth far outweigh the benefits.

For us, stealth mode delayed key learnings about our product’s fit with potential market segments, which likely amounted to a six-month setback.2 Fortunately, we realized our misconception and eventually changed course. I can’t say the same of other startups I’ve observed that are still operating in stealth, years after founding.

4. Are you riding a wave or a riptide?

As first-time founders, we had heard of startup accelerator Y Combinator’s legendary history incubating young founders and their early startups (e.g. Stripe, Airbnb, Instacart, DoorDash, Coinbase). When starting Savvy in the fall of 2019, we applied with our idea to build modern employee health debit cards (e.g. FSA, HSA, etc.). Good news: YC selected us for an in-person interview! Not-so-great news: a week before the interview, we concluded from customer research that our idea didn’t have legs.

Around this time, I received a cryptic email from a VC: “This looks interesting … check it out.” Attached was a draft copy of a new federal health insurance regulation that the Trump administration was working on. Employers could use payment cards similar to FSAs to let employees purchase their own health insurance plan from the open market (also known as the individual, ACA, or Obamacare market). This new option would disintermediate employers from selecting group health plans.

Our immediate thought was that this new regulation-driven market was going to be massive, and we could be first movers. Our next thought was that although we had never sold health insurance, we needed to pivot quickly given our YC interview in three days. A poorly researched idea seemed better than a bad idea, so we pivoted to building payment cards for employee health insurance.

In the final days leading up to our YC interview, we pored over the draft of the new regulation. One problem—we had little understanding of who would adopt this health insurance model. We needed to talk to customers, fast. An epiphany: the fastest way to talk to businesses was to just show up. We marched down Chestnut Street in SF and knocked on every small-business door. We proceeded to ask about their health insurance. Armed with these insights, when interview day came around, we confidently addressed the intense, 4-on-2 interview panel for precisely 10 minutes. Hours later, we received a call accepting Savvy into YC.

Once YC kicked off, our focus quickly became growth. Each week, YC partners pulled us into “group office hours” with five other startups to grill us on customer traction. These sessions lit a fire. Terrified of being caught with our pants down in front of our peers, we sprinted seven days a week to sell our product to whomever would listen.

When I say whomever, I mean literally anyone who would entertain a conversation. At YC’s first batch dinner, we recognized that drinks were missing from the menu. Founder thirst became our opportunity. We showed up with a cooler full of sparkling waters and a makeshift sign that read “Benefits & Bubbles.” In exchange for signing up with Savvy, we handed out drinks. To this day, that lemon-sparkling-water stand remains our highest-ROI marketing tactic.

Even without a clear grasp of what problem we were solving and for whom, we began selling. But therein lay our mistake. We were amateur artists painting frescoes, blindfolded. Our thinking at the time seemed intuitive. The market’s willingness to buy would show us whether there was a big problem to solve. If there was no demand for our product, the signal would be clear. If we saw strong pull with rapid word-of-mouth growth, the market fit would also be obvious. However, there is a dangerous in-between outcome, which is precisely where we landed: steady sales with no acceleration.

As customers ramped, it felt like we were winning. We even signed up several large companies, which 10x’d our user base overnight. In order to give these clients an incredible experience, we prioritized their feedback. With a two-person engineering team, we couldn’t always build their feature requests into the product, so we designed manual hacks. One large customer wanted Savvy to front all insurance payments on behalf of users. We began fronting funds (effectively a six-figure loan), remitting payment for users, reconciling everything in a spreadsheet, and billing the customer at month-end. We told ourselves that one day we would build technology to automate this, but for now, we’d take on the operations burden to keep the customer happy.

Now, doing manual things that don’t scale isn’t bad strategy. Oftentimes, it is the optimal way to scope features and develop customer loyalty. Unfortunately for us, our large, early customers all churned. We found ourselves in a death spiral—these poor-fit customers took up ops and eng time, but before we could release features catering to their problems, they left us. What we missed at the outset is that they were bad-fit customers all along, simply willing to try a bite of the apple. As the cracks of our early startup product became exposed, they were happy to throw away their unfinished apple and pick another. Ultimately, they weren’t desperate enough for our solution. Said another way, they didn’t have a problem that we could uniquely solve.

Key learnings from this part of our journey:

Take the time to build conviction in a specific problem before pitching sales and writing code. This could take weeks or even months, but early customer research will accelerate time to product-market fit later. During this process, it will be easy to paint convincing but dishonest narratives. It’s critical to be brutally honest. The problem must be obvious and specific, and you should know who “good fit” customers are. Focus only on good fits.

Perhaps counterintuitive: Pre-PMF you’re looking for overwhelming pull from the market or no sales at all. Remaining in between in the push-to-market territory for too long is dangerous. Some companies can find their way out of this riptide and onto a wave, but many (like Savvy) will not break free. If you find yourself paddling in the riptide, double down on customer research to understand whether your product or execution is limiting word-of-mouth adoption or if your assumptions on problem or market are incorrect. If you decide to keep building, be maniacally focused on customer behavior as you iterate and look for signs of market pull.

5. Losing conviction

Years after founding Savvy and emerging from Covid spring with $2.5 million in funding, we found ourselves once again searching for signal. After several months of tepid growth, we became pessimistic that our product was solving a big enough pain point for users. We ran experiments to see if we could sell to a different segment of the market who we thought more urgently experienced the problem our product solved. Again, we ran into issues selling. The buyer was apathetic and ill-incentivized to change. They often punted the buying decision to an outside advisor or broker. These advisors had their own set of misaligned incentives (welcome to U.S. health care), and the select few who were interested weren’t looking for the point solution we built.

When you bring a new product to market, you may make discoveries about your market or customer that reduce your belief in your product. These insights will not be immediate—it may take years of selling before arriving at a conclusion. You’ll likely try to pivot. Much has been written about the art of the pivot: altering your business while keeping one foot on the ground. Change the buyer, change your pricing model, change the product to serve a different user or use case, but stay focused on the same problem and market. However, pivoting may not work. What if you lose conviction in the market altogether?

Earlier this year, we were asking this very question. Savvy was largely a bet on a new, regulation-driven market. When we lost conviction in our market’s growth, we turned to our investor and former Andreessen partner Louis Beryl for advice. He lit a fire: “It sounds like you’ve lost belief. The worst thing you can do now is do nothing. What you do is up to you, but by the next time we talk, you should have made a move.”

We considered our options: shut down, restart, or sell the company. Shutting down requires little explanation—you let go of your team and shut your doors. Restarts are an option for companies like ours that still have cash remaining. The inherent difficulty is that after years focused on one problem with an existing team, you must start from scratch on something totally new, likely with a downsized team. Though hard to pull off, there are examples of success. Some years ago, a failing gaming startup performed a restart by taking its in-game communications technology and morphing it into an enterprise communications tool. This tool, of course, is now Slack.

The option that is perhaps most desired by founders, but that they have the least control over, is the elusive acquisition. Certainly at Savvy, an acquisition seemed most compelling—returns for shareholders, a landing spot for the team, and a chance for our product to live on. While the road was a winding, serendipitous one, we successfully closed on an acquisition by the market leader in our industry.

There is no one path to getting acquired, but I’ll share some tales and takeaways from our experience.

6. How to land an acquisition as a startup

If acquirers come knocking, serve them tea.

Some companies have acquisition targets on their backs seemingly since inception. They’ll receive unsolicited offers early, typically from a larger player in their industry. If you’re in this envious position, resist the urge to ignore these suitors even if the timing is off. When I was growing up in India, guests often showed up at our door uninvited. My family would always welcome them in, serve chai tea, hear the latest happenings, and send them off. Do the same with acquirers. Take the time to understand their interest and schedule infrequent touch points as you build. Savvy received an acquisition offer from Gusto early on. Naively, we declined without entertaining the offer and failed to engage them as we scaled. Years later when we were ready for acquisition talks, Gusto’s “strategy had shifted.”

Startups are bought, not sold.

As a nascent, unproven business, a startup actively looking for a buyer risks being perceived as a failing, problem-ridden entity. For this reason, as our advisor and One Medical CTO Kimber Lockhart explained to me, startups are bought, not sold. Is it possible to avoid this negative signaling? Yes, with some tact. When we spoke with potential acquirers, we hid our true intention behind the guise of partnership interest. We used a product partnership as our Trojan horse of sorts. As soon as we felt strong pull, we’d raise the idea of doing something “more strategic.” Now, is this a 100% transparent way to start a relationship? Maybe not, but it worked for us to successfully seed acquisition interest without raising doubts about our company. Proceed at your own risk!

Time is not your friend.

Acquisition processes are extremely fickle. They require escape velocity to overcome the inertia within big companies. We navigated many conversations where momentum seemed strong, only to be followed by radio silence. Time is not on your side—the more drawn-out processes become, the higher the likelihood of stalling momentum or a dissenting internal stakeholder.

When we signed the term sheet to sell Savvy, we granted a four-week exclusive due diligence period. Just two weeks into this period, the stock market began a free fall, which we now recognize as the start of the current recession. With each passing day, we’d wake up to the S&P opening 1% to 3% lower. For technology stocks, our nearest comps, it was a bloodbath. While the deal was nearing the finish line, the acquirer was taking their sweet time (to be fair, they had two weeks of exclusivity remaining). I knew that we were now in wartime—I needed to ratchet up the intensity to get the deal closed. On every call with the acquirer to negotiate the final purchase agreement, I told them we were ready to sign imminently. When our lawyers were slow to respond over email, I implemented twice-daily standup calls to increase their velocity. Anytime I received an email from the acquiring company’s CEO or CFO, I replied within the hour. If I didn’t hear back quickly, I sent a text message referencing my email and reminding them of my enthusiasm to get the deal done. While perhaps aggressive, I knew that a bear market is no time to do big M&A deals. Time was not on our side.

In just 48 hours, we finalized the legal documents and were in a position to sign. It was now Thursday. I knew that if we slipped into Friday, there was a risk the deal wouldn’t close until the following week. At 8 p.m. Central time, the CFO called me to say that they were missing signatures from their NYC-based board members. When I heard this, I was near ready to hop on a plane to New York and personally knock on the board members’ doors. I chose not to express this sentiment, but I let her know that I had an urgent personal issue on Friday and we needed to get this done tonight. She proceeded to text and call the outstanding individuals. Fortunately, they weren’t the types who went to bed without checking their phones, and submitted their consent. An hour later, the CFO called me again. This time, she was locked out of her bank account and couldn’t initiate the wire. She asked if we could push signing to Friday, given that it was now 10 p.m. her time. I could sense her fatigue, but even one day could risk the deal closing, with the turbulent macro backdrop. I pushed back and offered to call customer support on her behalf. Fortunately, she was able to get hold of her admin to unlock her account. Minutes later, we closed the deal.

Time is not your friend—don’t be afraid to have uncomfortable conversations to get a deal across the line.

Seek out decision makers.

There’s a narrow set of people who can make an acquisition decision quickly. Typically, you’ll find a C and O in their title. This may be obvious, but get in front of this person without wasting time with subordinates. Your path in matters—a subordinate introducing a deal is much less compelling than the CEO bringing you in. While this wasn’t our ultimate path in, your investors may have board-level connections. These board-level intros can often be the highest-impact path in, so pursue this angle aggressively if available.3

Build an acquisition funnel.

We ran our acquisition process like a sales pipeline—build a large top-of-funnel, qualify leads quickly, and spend the majority of time with likely-to-close prospects. At the outset, we identified around 50 companies in our industry that would be most interested in our product. The list included companies across health-care payments, insurance brokerage, insurance, and HR software. When culling the list, we took into account size and scale (with a bias toward well-capitalized, mature companies), ability to move quickly (with a bias toward venture or PE-backed companies), and our likelihood of penetrating senior leadership (insert plug for LinkedIn Sales Navigator).

Stop not till your (realistic) goal is reached.

Startup acquisitions come in a few flavors: IP (technology/product acquisition), team (acqui-hire), or both (company acquisition). An IP or company sale are most accretive and least likely. The acqui-hire is simply a vehicle for another company to interview and selectively hire your team, though surprisingly not a cakewalk to secure. You should be honest about what’s realistic for your company and let this outcome inform the types of companies you reach out to.

At Savvy, we were hopeful that the market would value the technology we had built. Many companies in the industry are unsophisticated when it comes to technology—our product, particularly with its unique payments features, would be an accretive acquisition. But we didn’t want to be left at the altar, so we ran parallel processes, one for company acquisition and another for acqui-hire. We started with 50 potential acquirers, but the list narrowed after two months of conversations (where we found a way in) to just a handful of interested parties. A Sequoia-backed health-care staffing company was moving fast to acquire our team. As we were finalizing that conversation, we received last-minute interest in a full company acquisition from the market leader in our industry. We were torn. We knew our team was excited about joining a hyper-growth, Sequoia-backed startup. That said, we wanted to maximize value and also see the fruits of our three-year labor live on. We decided to be transparent with the health-care incumbent to understand if they’d consider buying only our technology, IP, and customers, leaving our team out of the equation. Fortunately, they were enthusiastic. We were lucky to get both processes across the finish line.

Savvy was acquired by Take Command Health in June 2022, and much of our team joined Clipboard Health around that same time.

Thank you for sharing your story, Suril 🙏

Suril is currently advising startups on go-to-market while exploring new ideas in climate and fintech. You can follow his journey at

or connect with him on LinkedIn or Twitter.📣 Join Lenny’s Talent Collective 📣

If you’re hiring, join Lenny’s Talent Collective to start getting bi-monthly drops of world-class hand-curated product and growth people who are open to new opportunities.

If you’re looking for a new gig, join the collective to get personalized opportunities from hand-selected companies. You can join publicly or anonymously, and leave anytime.

❤️🔥 Featured job opportunities

Antimatter: Head of Design / Senior Product Designer (NYC)

Graphite: Sr. Director of Product—B2B SaaS (Remote, US)

Teal: Sr. Growth Marketing Manager (Remote, US)

Rabbithole: Product Manager (Remote)

Equi: Director, Product Management (NYC)

Noom: Head of Product Design (Remote)

Equi: Senior Product Designer (NYC)

Equi: Senior Product Manager (NYC)

Zendoor: Head of Product (Phoenix, AZ, Remote)

Playbook:Senior Product Manager (NYC, Remote)

If you’re finding this newsletter valuable, share it with a friend, and consider subscribing if you haven’t already.

Sincerely,

Lenny 👋

It also takes away from your ability to stay nimble. When we were faced with the decision to pivot or pursue a sale, our team weighed on us. We felt that a pivot would be painful at our size, and the potential products we could pivot to were limited if we wanted to keep everyone on the team. This reality led us to pursue a sale.

It’s challenging to quantify the real impact. Perhaps we would have received more leads and learned from an inability to close sales that our product wasn’t solving an urgent need. We wouldn’t have been fooled by our early growth metrics, and maybe we would have pivoted within months of launch to a different product. We’ll never really know.

Friendly reminder: Make it easy for your investors to work for you. Do the research, identify the person at the company you’d like to meet, and write the introductory email text.

As an early career person

Who aspires to be a founder one day

This was very eye opening!!

Thanks for sharing your journey @suril. Love the transparency. Lots to think about and would love to chat. LinkedIn.com/jay-sen