👋 Hello, I’m Lenny and welcome to a ✨ once-a-month free edition ✨ of my newsletter. Each week I humbly tackle reader questions about product, growth, working with humans, and anything else that’s stressing you out at the office.

If you’re not a paid subscriber, here’s what you missed this month:

Q: I keep hearing that I need to improve my product’s positioning, but I’m not sure what that means and how to do this. Where do I start?

When I think positioning, I immediately think of one person: April Dunford. April is the author of the best-selling book Obviously Awesome, which to me is the definitive book on positioning, and spends her days working with companies of all shapes and sizes helping them nail their positioning.

When I received this question, I cold-DM’d April to see if she’d be interested in tackling it, and thankfully she agreed 🎉

Below, you’ll find what I believe is the most succinct and practical guide to nailing your product’s positioning. Let’s dive in!

For more from April, check out her Twitter, website, and book.

A quickstart guide to positioning

My first job out of school 20 years ago was as a product marketer at a startup. I was assigned to work on a product that had been conceived as a “Microsoft Access killer” that supported SQL and could run on people’s desktops. Back then, SQL databases only ran on big servers. But after a significant marketing effort, we had barely sold 200 copies. We knew it was time to wind it down, but before we did, we decided to check in with buyers to see how upset they would be when we did. Being the new gal, I got the job to make the calls.

The first 20 conversations I had were exactly the same:

Me: Hi, I’m calling to find out how you’re using our product.

Customer: Sorry, lady, we don’t have that.

Me: Um, well, my records show you paid $100 for it on Jan 22nd?

Customer: Oh, that thing—yeah, we tried it, we don’t use it now.

Our decision to kill the product was going to be easy.

But then I did call 21. “Your product made me the hero of the sales team!” the customer shouted. At his company, sales folks traveled to their customer, took orders on paper, and then returned to the office to enter them in the order system. Orders were often incomplete or full of errors. Our product was installed on laptops with the order system, allowing sales to take orders in the field and then sync with the SQL database back in the office. “We’re doubling sales! That SQL feature was a game changer for us!” he raved. I thanked him and carried on with my calls.

I had 20 more conversations with 20 more customers who barely remembered purchasing before I hit another fan of the product. His story was similar—he used our product on mobile devices for field service agents who could update their system in the field, then sync with the database at headquarters. “We’ve increased service capacity by 60%. Your product is a game changer!” he said.

In the end, I talked to 100 customers: 94 didn’t even know they had it, 6 had transformed their business with it. We didn’t exactly have product-market fit in the Sean Ellis sense.

I relayed my findings back to the exec team. Instead of killing the product straight away, they decided to take a shot at repositioning our “Microsoft Access killer” as an “embeddable database for mobile devices.” The product took off.

A year of massive growth later, we were acquired by a big database company, where the product spawned a product family that generated hundreds of millions in revenue. Over 20 years later, this “failed” product still runs on mobile devices all over the world.

Positioning isn’t new—but it’s deeply misunderstood

This experience sparked my lifelong obsession with positioning. How could we have known in advance that our product was simply mispositioned? Was there a way for us to figure out what really set our product apart, what our value for customers really was, and what customers we should be targeting?

Positioning is not as well understood as you might think. If I put a dozen senior marketers in a room together and asked them to define positioning, I’d get a dozen different answers. When I talk about positioning at conferences, I sometimes start by defining what positioning is not: Positioning is not equivalent to messaging. It isn’t a tagline. It’s not your brand story, nor is it your vision or your “why.” It is not, as one CEO attempted to convince me, “everything you marketers cook up over there.”

So what is it, and, more importantly, how do we do it?

Defining positioning

Here’s how I define positioning:

“Positioning defines how your product is a leader at delivering something that a well-defined set of customers cares a lot about.”

Yeah, that sounds a bit complex, but positioning is made up of a distinct set of components. Those components and their relationship to each other is where the magic happens. We will get to that in a minute.

Positioning as context setting

Positioning is like context setting for products. It’s a bit like the opening scene of a movie. The opening scene gets us oriented. It answers the big questions: Where are we? What year is this? What’s happening? How should I feel? Who are these people? Once we have established some context, we can settle in and pay attention to the story’s finer details.

Let’s take the opening scene of Apocalypse Now. We see a grove of peaceful palm trees swaying the breeze and maybe you’re thinking, “Hey, maybe it’s not apocalypse right now,” but then you notice some smoke and a helicopter quickly flies past. Suddenly the palm trees burst into flames as Jim Morrison screams, “This is the end, my friend!”

We realize we are in the middle of the Vietnam War and it’s the apocalypse right now alright. Then slowly, the scene shifts and we see Martin Sheen’s face. He’s drinking and smoking, his hotel room is a total mess, and he’s clearly in psychological distress. He walks over to the window and we get the first line of dialogue in the movie: “Saigon. Shit. I’m still only in Saigon. Every time I think I’m gonna wake up back in the jungle.”

We are exactly 4 minutes and 45 seconds into the movie, but we know a lot about what’s happening. We are in the middle of the Vietnam War, and in Saigon specifically. Our lead character has been there before and has some pretty bad PTSD as a result. We also get the tone of the movie and we know it’s going to be an intense couple of hours. The opening scene positions the movie by answering our big questions about who, what, where, and why so that we can settle in and focus on the details of the story within that context.

Similarly, positioning your product in a market orients the customers and conveys a lot of valuable information. Your positioning context sets off a really powerful set of assumptions about who your product competes with, what features your product should have, who the product is intended for, and even things like what the product should cost.

Suppose I pitch you my product, and all I tell you is that it’s a “CRM” and that’s it. What assumptions would you make about my product before I got to page two of my pitch? You would assume my competition is Salesforce—they are the leader in that market. You would assume I sell to the head of sales. You would assume my product has a set of features—tracking deals and accounts, for example. You would even make pricing assumptions. Salesforce is the leader in the market, so you would assume my product costs less than that.

Good positioning sets off a set of assumptions about my product that are true. Bad positioning sets off a set of assumptions about my product that aren’t true—leaving your sales and marketing teams to do the work of undoing the damage your positioning has already done.

If I were to tell you my product was “email,” you would have a very different set of assumptions than if I positioned it as “chat.” There is a large overlap in features between the two, but as buyers, we expect email to filter spam, allow us to organize and store conversations, and integrate with a calendar. Our expectations for chat are different. We expect instant delivery, a way to see if someone has received or viewed our message, etc. A new product could be positioned in either market, but great chat is lousy email and vice versa. A shift in positioning can completely transform how we perceive a product and can mean the difference between success and failure.

A positioning statement can’t help you

So if positioning is so important, how do we do it? Let’s start with what not to do.

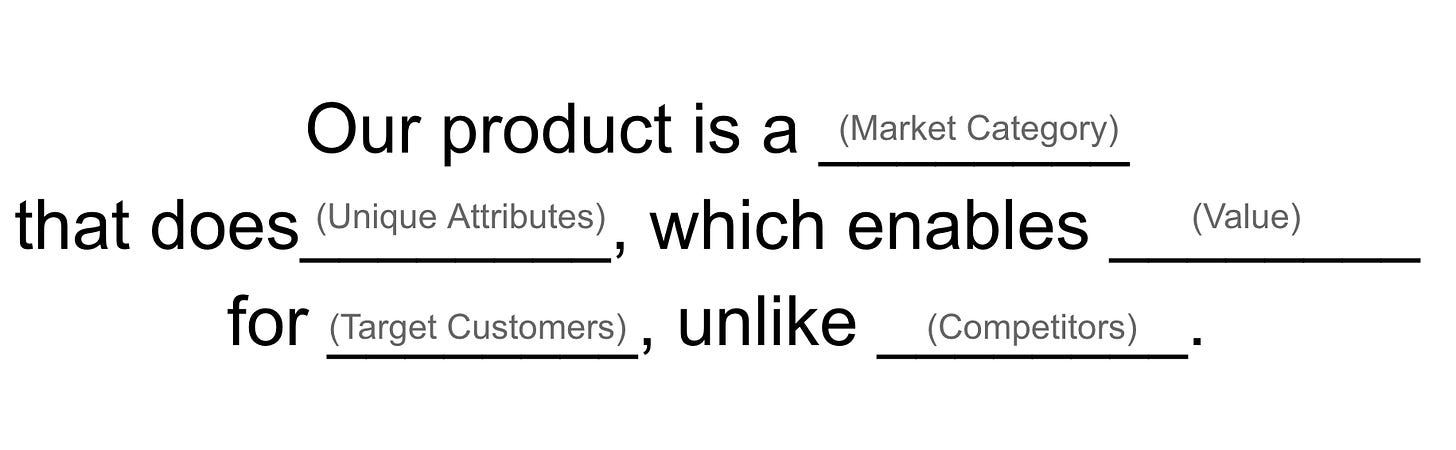

For many people, positioning was taught to them in school using the “positioning statement.” It’s a sort of Mad Libs fill-in-the-blanks exercise. The blanks are things like market category, value, competitors, etc. Typically it looks something like this:

I believe this exercise is not only pointless but potentially dangerous. The exercise assumes that there is only one answer for each of the blanks and you simply “know” what it is. However, most products could easily be positioned in multiple different market categories, with different competitors, providing a different value for different kinds of customers. How would this exercise help me understand that my “Microsoft Access killer” was really an “embeddable database for mobile devices?” The answer is that it would not.

The 5 components of positioning

So how do we find the best positioning for our offerings? This question vexed me as a marketing executive across seven successful startups (and the six big companies that acquired them). I read books! I took courses! Everyone agreed that positioning was the marketing bedrock we built our entire go-to-market strategy around, and yet there didn’t seem to be a methodology for actually getting it done. I decided to figure it out.

I started with an engineering mindset. I decided we could break positioning up into its component pieces, find the best answer for each piece, bring the pieces back together, and voilà—great positioning.

Breaking positioning up isn’t hard, because we generally agree on the components. These are, in essence, the blanks in the positioning statement. The components are:

Competitive alternatives

Differentiated “features” or “capabilities”

Value for customers

Target customer segmentation

Market category

Easy. Now all we have to do is figure out how to get the best answer for each component. Here’s where things get a little tricky.

Each component depends on the others

If you look at the pieces, you quickly understand that each component has a relationship with the others. For example, the unique value that you can provide to customers is completely dependent on your differentiated features. Your differentiated features are only “differentiated” when you compare them to competitive alternatives. Your best-fit target customers are customers who really care a lot about your unique value. And lastly, your best market category is the context you position your product in such that your unique value is obvious to your target customers. So if every piece has a relationship to every other piece, where do we start?

For two years, I didn’t think there was a starting point. I attempted to find the best positioning for my products by picking an arbitrary starting point (for example, differentiated features) and then working my way through the others to get a “candidate positioning.” I would then test it on prospects, and if it worked, we ran with it. If it didn’t, I tossed it out and repeated the process to get another candidate to test.

The drawback to this method are obvious to anyone who’s worked at a startup: it just took too long! While I was out testing candidate after candidate, the sales, marketing, and product teams were stuck in a holding pattern waiting.

A customer-centric methodology

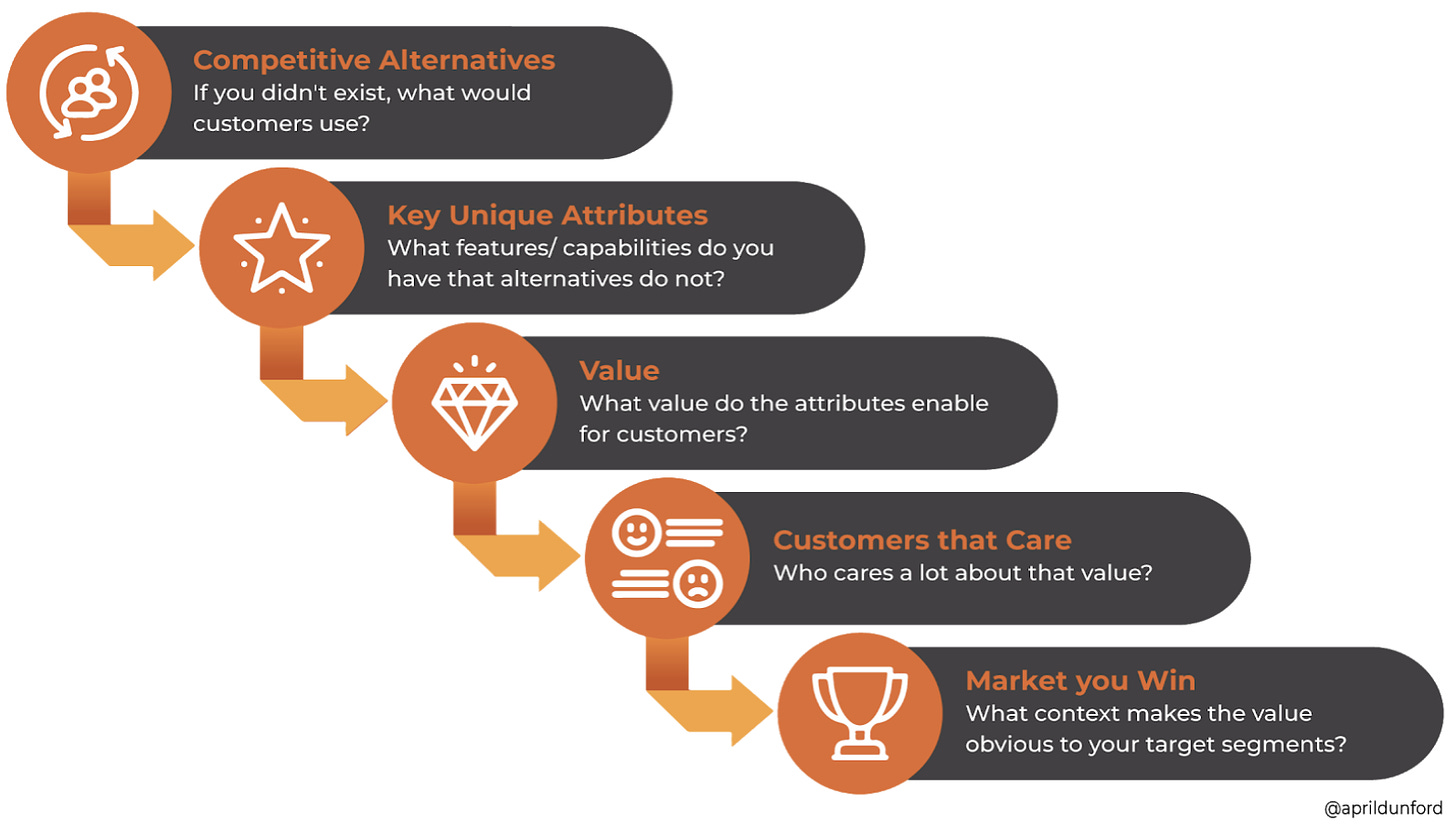

Eventually, Clayton Christensen solved this problem for me. I was reading everything I could get my hands on about the Jobs to Be Done theory, and I had the realization that the starting point had to be competitive alternatives. If it wasn’t, what we ended up with was positioning that sounded good in the office but didn’t work with customers because it wasn’t differentiated. The flow has to look like this:

We start with competitive alternatives, or what customers would do if our solution didn’t exist. Once we have that, we can ask ourselves, “What do we have that the alternatives do not?” That gives us a list of differentiated features or key unique attributes. We can then go down that list and ask ourselves, “So what for customers?” Put another way, what is the value those capabilities enable for our buyers? Once we understand what our differentiated value is, then we can move to customer segmentation, or who the customers who care a lot about our value are. There is likely a wide range of buyers who care about that value, but certain customers care a lot more than others. What are the characteristics of a customer that makes them care a lot about your differentiated value? That gives us an idea of who our best-fit customers are. Lastly, we move to market category. Our best market category is the context we position our product in such that our value is obvious to our target customers. Put another way, it is the definition of the market we intend to win.

An example: Janna Systems

Let’s walk through an example of how this works. Early in my career, I ran marketing for a company that positioned its product as an enterprise CRM. This was ages ago when Salesforce was still focused on SMBs, and the gorilla in the enterprise CRM market at the time was Siebel Systems. Unsurprisingly, every time we got a meeting with a customer we got the question, “So how are you better than Siebel?” That was a bad question for us because, by almost every measure, they were better than we were. They had 8,000 employees and we had a couple dozen. They had $2 billion in revenue; we did less than $2 million. They had 400 customers and we had 6. We did, however, have two differentiators.

The first was a feature that they couldn’t match. Specifically, we could model relationships in a different way. Most CRMs model the relationship between people and an organization. Our CRM let you model relationships between people, independent of their organization. An example would be that we could show that two people sat on a board together even though they work for separate companies. No CRM then (or even today, for that matter) could do that. The problem was that, for the most part, we didn’t do a good job of articulating the value of that. We showed the feature in every demo, and when customers asked us what they would do with that feature, our reply was “Anything you want!”

Coming back to the process I laid out in the previous section—our competitor was obvious; it was Siebel. Our differentiator was the ability to model relationships in a different way. What we hadn’t figured out was what the value of that feature was and what types of customers cared a lot about it.

Eventually, we landed a deal with an investment bank. Working with that customer helped us understand that the value of our feature was that companies could get insight into interpersonal relationships, which sales teams could use to start new sales conversations and understand who might have influence over a deal in process. For companies that relied heavily on personal relationships (e.g. investment banking, private client services), our product was a game changer.

Going back to the positioning process, we could now fill in value and customers who care. This was super-important for our go-to-market strategy. We shifted our sales and marketing efforts to selling to investment banks, where we had a distinct advantage over Siebel.

Lastly, we decided to make a change to the market category. Clearly, we couldn’t win Enterprise CRM, but we could win CRM for Investment Banks. Positioning ourselves that way helped banks find us and helped us clearly differentiate from Siebel. This shift in positioning allowed us to grow very quickly over the next 18 months, from under $2M to close to $80M. Our plan was to shift the positioning to CRM for Financial Services as we expanded to retail banks and insurance companies. We didn’t get the chance to test that positioning evolution, however—Siebel acquired us for $1.3B.

Common mistakes

Once you understand the flow conceptually, it’s pretty easy. But that doesn’t mean there aren’t a lot of ways you can mess this process up. Here are the three most common traps:

Trap 1: Defining competitive alternatives as any possible competitor

The most common mistake I see startups make is in how they define the competitive alternatives in the first step. A better way to think about competitive alternatives is to ask yourself, “What would a customer do if your offering didn’t exist?” Sometimes the answer to that question is “Do nothing.” What that really means is the customer would stick with their current way of solving the problem. That could mean using a spreadsheet, using a manual process, or hiring an intern to do it. In enterprise software, we typically lose 25% of deals to “no decision.” Your positioning needs to position you against the status quo if you want to convince customers to act.

Trap 2: Creating “phantom competitors”

Next, I see companies listing what I would call “phantom competitors” in step 1. Phantom competitors are companies that theoretically could compete with you; you just never actually see them or lose to them in deals. Until you do, you are watering down your positioning by trying to position against them. Step 1 in the positioning process is to identify what your customers see as alternatives. This isn’t a test of your internet research skills, and just because a company could compete with you doesn’t mean they ever will. The product team might want to keep an eye on them as a future competitive threat, and if you do start to see them in deals, you can adjust your positioning at that time. Until then, you will weaken your positioning by trying to position against competitors your customers never even consider.

Trap 3: Assuming that you have to create a new market category to grow

When selecting a market category, you can either choose to position your product in an existing market category or attempt to create a new category in customers’ minds and then position your product as the leader in it.

The first option allows you to use what customers already know and understand about a market to help them understand what your product is and what makes it uniquely special. If I tell you my product is an “embeddable database for mobile devices,” you have the benefit of understanding what a database is. “Embeddable” and “for mobile devices” narrows down the field of alternatives to a market niche where this product is not only different from the leaders in the more generic “database” market category, but much better for a particular kind of buyer.

Creating a new market category, on the other hand, is where you invent a new frame of reference for customers. The obvious downside to this strategy is that you first have to make the category mean something in the customer’s mind before it can serve as a meaningful context. So instead of being an “embeddable database for mobile devices,” you choose to be a fluflommer. Yep, a fluflommer. Customers have no idea what that is because you’ve just invented it, so be prepared to spend a significant amount of time and effort making that term mean what you want it to mean.

There is an assumption that the payoff for creating a new market category is that you will dominate the market as it grows. In my book, I tell the story of Eloqua and how founder Mark Organ created the Marketing Automation category and did exactly that.

Unfortunately, history teaches us that companies that create market categories often lose in the long run to companies that gained a market foothold after the hard work of creating the category was already done.

This is why we use Google and not Ask Jeeves. This is why we use Facebook and not Myspace. In fact, 90% of tech companies that have gone public over the past five years have been positioned in existing markets rather than creating new ones. Many of the examples of category creators started out positioning themselves in existing markets before they later stretched the boundaries of that category. Salesforce was a niche play in the CRM space until it had hundreds of millions of revenue. Gainsight was in the survey software market until it had hundreds of millions of revenue. It’s much more common for startups to start out positioning themselves in an existing category until they have the money and momentum required to re-draw the lines around that category.

Positioning—you’ve got this!

Positioning is a misunderstood concept, but I believe that if you master it, it can be the most powerful strategic tool you have at your disposal. If you are interested in learning more, I go deeper on this topic in my book, and I’ve got a set of templates to go with it that you might find helpful.

🔥 Job opening of the week: Airtable

✨ Airtable is hiring for a Full-Stack Engineer and an Engineering Manager ✨

Additional opportunities:

Product: Cerebral, Kudo, Plume, Prenda, Rocketplace, UserLeap

Growth: Alloy, BasisOne, Prenda, SpaceX Starlink

Design: Ashby, Berbix, Office Hours, Levels, Primer, Runway, Watershed

Engineering manager: Cerebral

Fullstack engineer: Alloy, Cascade, Centered, Icebreaker, Iggy, Primer, Runway, Snackpass, Stytch, Sunroom

If you’re finding this newsletter valuable, consider sharing it with friends, or subscribing if you aren’t already.

Sincerely,

Lenny 👋

Going through positioning work for my startup now and this is fantastic

Loved this!