What is a good payback period?

Benchmarks for good, great, and exceptional payback periods based on guidance from 16 growth experts

👋 Hey, Lenny here! Welcome to a 🔒 subscriber-only edition 🔒 of my weekly newsletter. Each week I tackle reader questions about product, growth, working with humans, and anything else that’s stressing you out about work. Send me your questions and in return I’ll humbly offer actionable real-talk advice.

Q: What is a good payback period?

To answer this question, like I did with our look at retention, I brought out the big guns. I polled the smartest growth people I could get hold of and asked them what payback periods they expect when investing in, or advising, startups. Everything that you find below is based on the collective wisdom of these superstars: Adam Grenier, Andrew Chen, Andy Johns, Bill Trenchard, Brian Rothenberg, Casey Winters, ChenLi Wang, Dan Hockenmaier, Darius Contractor, Elena Verna, Jamie Quint, Josh Buckley, Mike Duboe, Naomi Ionita, Sriram Krishnan, and Yuriy Timen 🔥

What is a good payback period?

Broadly, the consensus is:

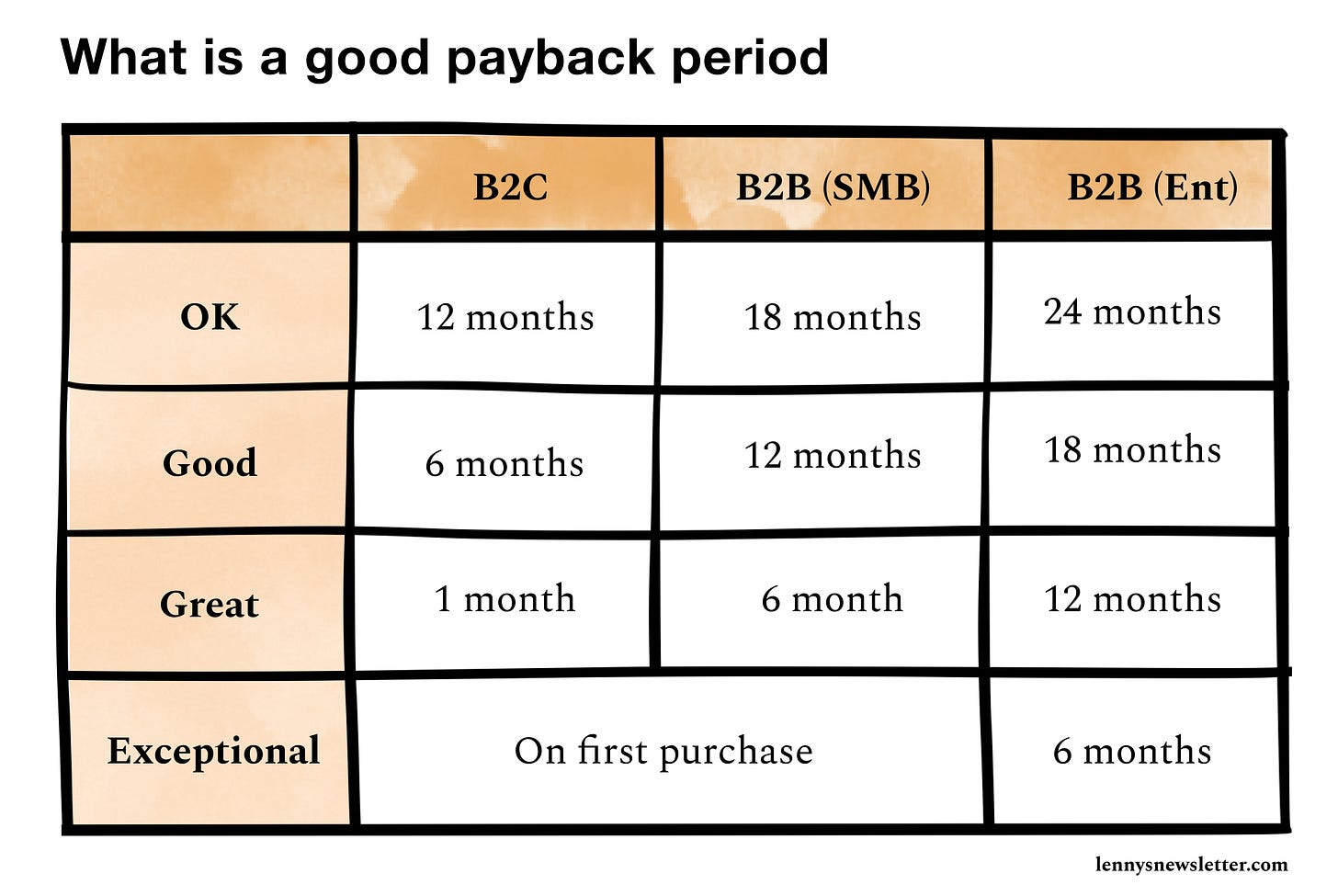

For B2C businesses, a payback period of less than 1 month is GREAT, 6 months is GOOD, and 12 months is OK. And the exceptional cases can pay back their acquisition costs on the first transaction.

For B2B businesses selling to SMBs, less than 6 months is GREAT, 12 months is GOOD, and 18 months is OK. And similarly, the exceptional cases get their customers to prepay their contract and recoup all acquisition costs up-front.

For B2B businesses selling to enterprises, less than 12 months is GREAT, 18 months is GOOD, and 24 months is OK. The exceptional cases can pay back their acquisition costs within 6 months.

Here’s a handy chart summarizing the findings:

What exactly is payback period?

The payback period is the amount of time that it takes to earn back the cost of acquiring a new customer. For example, if it costs you $100 to acquire a new customer (e.g. running FB ads) and you make $25 per month from that customer, your payback period is four months.

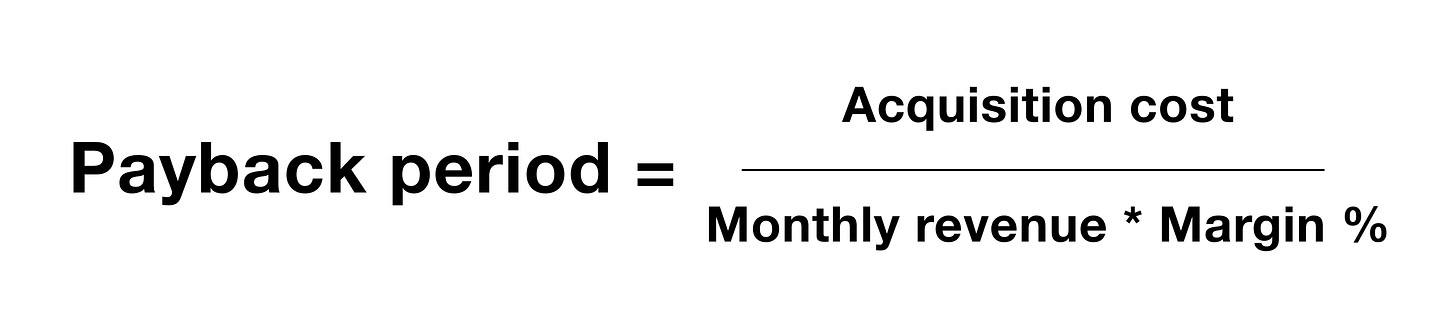

How do you calculate payback period?

To calculate your payback period, simply divide your CAC by your gross profit:

The biggest mistake founders make when calculating their payback period is looking at revenue, without subtracting the cost of good sold (i.e. margin):

“If a startup acquires a customer for $100, and that customer generates $10/mo in revenue, with 80% gross margins (or $8 of monthly gross profit), the payback period on a gross profit basis is $100/$8 = 12.5 months. Not 10 months, if you were just looking at revenue. As my former CFO used to say, ‘Revenue doesn’t pay our salaries—gross profit does.’ You have to take out the cost of goods sold, and many people do not.”

—Brian Rothenberg

Also:

“Including brand search in your paid campaigns bucket will lower your payback period, and I’d consider that cheating.”

—Elena Verna

Why is tracking payback period important?

The shorter your payback period, the more quickly you can reinvest your cash into growth, and the faster you’ll grow. If, for example, you spend $100,000 on growth and get paid back in three months, while your competitor takes six months, you’ll be able to spend twice as much money on growth without having to raise one additional dollar.

Increasingly, startups are focusing on payback periods over LTV/CAC ratios because accurately calculating LTV for an early-stage company is highly suspect. This is the same reason you don’t want long payback periods for early-stage companies:

“The way I think about it is the more data you have about your customers over time, the better you can predict actual lifetime value. An early-stage startup has very little data, so if it has a long payback period, it’s not guaranteed there will be a timeline that pays off at all due to all the assumptions. A late-stage company has over a decade of cohorts it can compare new customers to, to predict what they will look like in six months, one year, two years, etc.”

—Casey Winters

Are higher payback periods OK?

Yes! There are a handful of cases where having a higher payback period is actually a good thing.

1. When you can confidently predict your LTV

“It is important to remember that what really matters is the ultimate LTV of the customer. If your product is incredibly sticky (i.e. more than 5-year LTV) or shows high growth in account (through additional usage fees/upsell/cross-sell), an 18-month payback period may be really good.”

—Bill Trenchard

“Generally it’s the case with larger companies to have payback periods of 18 to 24 months. These are companies with large balance sheets, that can float it, in more competitive categories. They generally have a lot of data on their LTV curve and how it performs over time.”

—Josh Buckley

2. When you’re a mature business and can think longer-term

“In some cases, with mature enterprise SaaS businesses that have predictable LTVs and renewal data, as well as multi-year contracts, I’ve seen payback periods stretch as far as 24 months.”

—Yuriy Timen

“At different stages of maturity (5+ years, 10+ years), you can probably shift the OK, Good, Great designations from the summary above up one level because you have more confidence in the lifetime value and therefore the payback. Usually you have more cash as well. In those cases, let’s say a consumer business that is 10 years in and getting payback in one month, it should really be trying to grow more aggressively by extending its payback period, probably leaving a lot of profitable growth on the table by staying at one month.”

—Casey Winters

3. When you’re optimizing for growth

“I’ve seen payback periods as high as 5 to 7 years. There are good reasons a company might tolerate that, such as much-needed fuel into a growth loop, it’s an investment into key target market segment, or it’s just early inefficiency that will take some time to optimize. Not every channel comes out of the gate with good payback period, after all.”

—Elena Verna

“The payback period you choose to target is highly contingent on the stage of the business and how quickly you are trying to grow. Lower payback periods are not objectively optimal, because they may mean you’re leaving growth on the table.”

—Dan Hockenmaier

“So much of it depends on how one is maximizing revenue vs. profit. The same company could be 8 months if it was profit-focused or 24 months if revenue-focused, and feel good about each.”

—Darius Contractor