On asking for help (even when you really don’t want to)

Step-by-step tactics for facing your fears and making the ask—including templates and example scripts

👋 Welcome to a 🔒 subscriber-only edition 🔒 of my weekly newsletter. Each week I tackle reader questions about building product, driving growth, and accelerating your career. For more: Best of Lenny’s Newsletter | Hire your next product leader | Podcast | Lennybot | Swag

Photos from recent reader meetups 🥰

If you’d like to attend (or host!) a meetup, join our paid subscriber Slack and find your local city channel. Learn more here.

People sometimes believe that asking for help will make them look weak, or even incapable of doing their job. But in fact, it’s the complete opposite. Every successful person you know became successful because they were skilled at asking for help. What I’ve heard repeatedly from the many leaders I’ve met, and have found to be true in my own career, is that knowing when and how to enlist support is a career unlock. You’re slowing your trajectory if you don’t build this muscle.

In her phenomenal inaugural guest post, Newsletter Fellow Natalie Rothfels shares a step-by-step guide for when, who, and how to ask for help, including how to get over your fears about asking for help, practical templates, example scripts, and tactical advice—rooted in her coaching practice and personal experience.

Natalie is an executive coach who works with co-founders and executive teams, helping them build interpersonal skills to become more effective leaders. She spent a decade as a product manager building educational tools at Quizlet and Khan Academy and now helps leaders build their emotional intelligence, influence, relationships, and ability to navigate conflict. She is a certified Internal Family Systems practitioner and a facilitator for Stanford Graduate School of Business’s Interpersonal Dynamics course, aka “Touchy Feely.” She also recently launched The Ripple Deck, a facilitation tool for building connection. You can follow her on LinkedIn and Twitter.

In late 2021, after pushing myself to the edge of burnout, I made it a goal to ask for help at least once a week.

I requested testimonials from clients who had ghosted me after months of work together. I asked strangers for financial support on multiple Kickstarter campaigns. I solicited words of affirmation from peers to help boost me up. I even asked some of my family to quietly listen while I expressed anger about my childhood.

None of this came naturally to me. I’ve prided myself on being independent, hyper-resourceful, and not “needing” anyone, especially in a professional context. Being dependent on others felt vulnerable and risky. And because of that, I was willing and able to work 10 times harder to avoid the vulnerability of asking for the help I needed and deserved. When my body and my brain gave up, I lost joy for a job that was otherwise a perfect fit. My previous strategy was no longer an option.

Three years later, I can say that learning to effectively ask for help has been the biggest transformation in my personal and professional life. I can sleep at night without the burden of chronic overwhelm and rumination. I have healthier, reciprocal relationships that both challenge and support me. My work is more focused and productive than ever before.

Since learning that lesson for myself, I’ve spent hundreds of hours coaching product leaders, founders, and executives to incorporate this skill into their lives too. Most clients logically understand the upside of asking, but few can anticipate how much emotional energy it unlocks.

Take it from my client Meena (not her real name):

“The exhaustion of subconsciously assuming I have to do everything on my own robbed me of agency, joy, and so much energy in my work. Shifting this has been radical for me in terms of my relationship to myself and to my work.”

This tendency to hold onto everything can be especially salient among product managers, who are lauded for their “ownership” of problems. It’s hard to be high-agency, take radical responsibility, be everyone’s unblocker, build great products—and do it alone. When done well, asking for help does not diminish your ownership or credibility. It increases your agency, builds higher-trust relationships, and models a willingness to put your vulnerability aside for the sake of the work. That can also help your peers and reports, who will see you modeling a practice that keeps a team psychologically safe and sustainable to work in.

I’m writing this post now to share everything I’ve learned about asking for help so far. I’ll help you navigate the fears associated with asking and give you a toolkit for making your asks more effective, including template scripts you can start using today, based on the ones I created for myself and my clients.

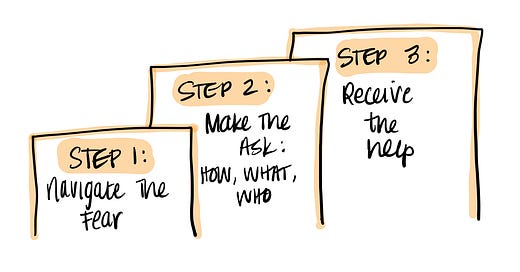

Step 1: Navigate the fear

Making an ask is vulnerable for everyone, and can provoke fear, anxiety, and stress. One client just this week expressed the fear in a way that I’ll never forget:

“Asking for help is a sign of weakness, and weakness is a sign of death.”

These emotions can be paralyzing, preventing you from seeking the support you desperately need to unblock your work.

My client Meena’s story is a great example:

Meena is a Group Product Manager with 10 years of experience, currently working at a 300-person Series C SaaS startup. She came to me struggling with an overwhelming workload and on the brink of burnout. As a player-coach, she manages PMs, has her own IC growth work, and supports the hiring and onboarding process for new talent.

I noticed immediately that Meena was spending her whole day helping her teammates and putting her own priorities last. Her “real” work didn’t start until after 5 p.m., when she was finally done with meetings. It wasn’t just a matter of poor time management. She was subconsciously avoiding her product work; it felt more ambiguous than the clear needs of her team, and she didn’t know the “answers” to the problems she was supposed to own. Rather than putting some draft ideas to paper and gathering initial feedback, she refused to share anything half-baked out of concern that others might see her as incompetent or dumb. She’d sit for hours at a blank screen while her inner critic repeatedly said, “This is your job. You’re so bad at this. You’re going to get fired if you don’t finish this tonight.”

The reality was that she actually was good at her job—great, even! But when she was in that state of fear, she couldn’t see her own skills and agency clearly. No agency, no action. She was blocked.

When I asked Meena when the last time was that she’d asked for help at work, she looked at me with confusion. She had never even imagined the possibility. Her fears of looking inadequate obfuscated the choice.

To be fair to Meena and all of us, these fears can absolutely be well founded. There are times when asking for help can lead to degraded trust or, in the worst case, being fired. But if done with consideration and skill, you are more likely to encounter the best case: you get the help you need, and your boss and your team get their needs met too.

From my own experience and from working with countless clients, I knew asking for help could open a world of possibilities. Spoiler alert: it ended up working for Meena too. She experienced a noticeable and lasting shift in stress and overwhelm. Her team relationships became more reciprocal and less stuffy. Once she got past her fears, she was even asked to expand her leadership to two more teams. And she could take on the new scope sustainably—good for her career, good for the company.

Meena’s case may seem extreme, but she’s not alone. Most of my clients have fears come up when I ask this same question.

Boiled down, the fears sound like this:

Fear of being a burden: “If I ask for help, I’ll be imposing on others who are also busy.”

Fear of appearing incompetent: “If I can’t handle this on my own, they’ll think I’m not qualified for my role.”

Fear of rejection: “If I ask for help, they’ll just say no.”

Fear of losing control: “If I involve others, I might lose autonomy over my projects.”

Fear of uncertainty: “If I ask for help now, it might negatively impact my future opportunities or relationships.”

Fear of the cost: “If I ask for help and it doesn’t solve my problem, I’ll have exposed my vulnerability for nothing.”

In Meena’s case, she was most afraid of appearing incompetent to her manager. Her manager had given her increasingly more responsibility during Meena’s two-year tenure and she didn’t want to be seen as a failure.

But the starting point for learning this skill is not running to your boss with your arms flailing. It’s befriending your fear enough that you can begin by making any ask at all—usually first to a friend or peer. It really helps to have someone to process with, but here are a few steps you can take on your own to address your fears.

Phase 1: Increase awareness of your emotions

Your body is likely sending you all sorts of signals that say, “I’m scared.” Become familiar with your body’s vocabulary of fear. If you are unattuned to how fear shows up, it’s difficult to work with it. I often tell clients to create an “emotion log” (here’s a template!) to start increasing their awareness of when and how the emotion shows up, what triggered it, and what its supportive function is.

Example: Meena’s fear lived in her chest and would send constriction all the way up her neck, making it hard to speak. She noticed it most acutely when she had said yes without knowing whether she had the capacity (skills or time) to succeed at the task.

Phase 2: Allow the fear without changing it

All fears are valid, even if they’re not true. Name it to tame it. Articulate what you’re afraid of. Acknowledge how the fear serves and protects you, and allow it to be present without making it wrong.

Sometimes we are even scared of acknowledging our fear! This extra layer of fear can make it difficult to fully acknowledge how scared you might be, so be compassionate and allow yourself the time you need at this step.

Your goal is to really hear the story that your fear has, without second-guessing it, debating with it, or overriding it. I often ask my clients to imagine the fear as a little character sitting atop their hand that we can have a conversation with. Hear out your fear.

Example: Meena eventually acknowledged something like “I’m afraid that if I ask for help, my manager will think I can’t handle the responsibility they’ve given me. My fear helps me stay small and play it safe so I ensure I won’t feel like a failure.”

Phase 3: Offer yourself security by shifting the narrative

Cognitive reframes aren’t always effective for transformational work, but they can be enough to shift us in the moment toward possibility rather than pessimism.

At this step, the goal is to offer yourself internal security. Try these shifts:

“Asking for help makes me a burden” → “People really appreciate being asked and valued for their expertise.”

“Asking for help makes me look weak or incompetent” → “Demonstrating that I know what I don’t know is a key leadership competence.”

“People will think less of me if I ask for help” → “People respect and appreciate my vulnerability, and expressing my needs will allow them to do the same.”

“My boss will be annoyed that I can’t do it alone” → “Leaders want my work to succeed and need to know when that’s at risk.”

These narratives are not just mental gymnastics. You have firsthand experience to draw on, too. How often do you perceive someone as burdensome, incompetent, or weak when they make a thoughtful, unentitled ask? Probably rarely.

Phase 4: Design and enact an experiment

We expand the edges of our fear through experimentation and data gathering, not just self-awareness.

As I worked with Meena to peel back the layers of fear and stress, we uncovered some key issues: Meena was heavily overcommitting herself, not involving her peers early enough in her thinking process, and assuming her team couldn’t step up more. She was slow to produce work, and she made reactive decisions based on fear and urgency.

I asked her to design an experiment that could yield real data that might challenge her mental models (namely, “I must do this alone or I will be seen as ineffective”).

Her first experiment was designed to verify whether her PM and engineering peers perceive her as ineffective or burdensome when she asks for help. (They did not. She was brave enough to reveal her insecurity, and they both empathized with it.)

It pays to practice these strategies early and often. As you grow in your career, you’ll encounter more projects that you don’t immediately know how to tackle. New, bigger, and more ambiguous projects often feel more threatening because you’ve never successfully done them before! With enough practice, you’ll shift away from the fear of asking to proactively anticipating where you might get stuck and who you can ask well before you ever need it.

Step 2: Make the ask

Once you’ve navigated the fear, the next step is the big one: making the ask. This starts with structuring your ask effectively. Then, we’ll determine what help you need and who you can ask, using Meena’s situation as an example.

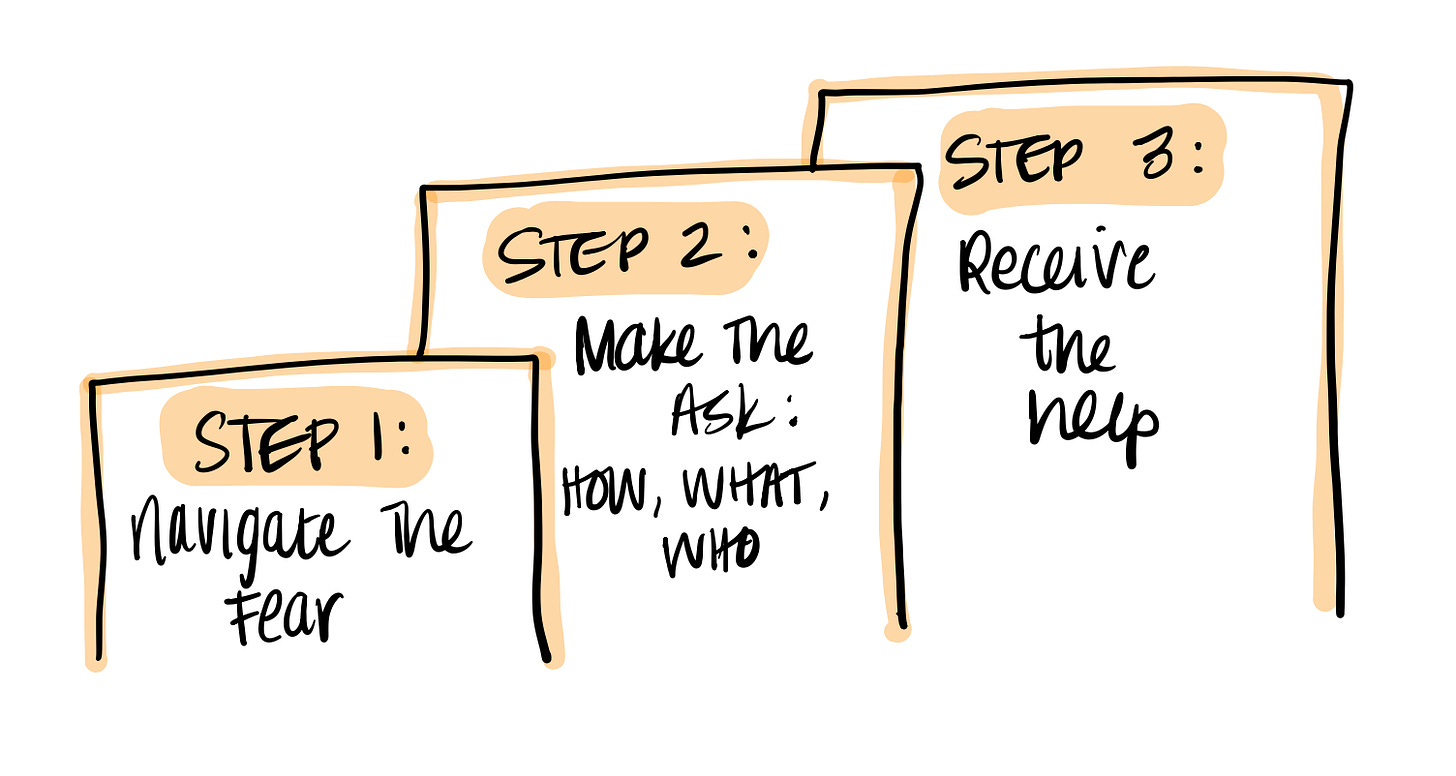

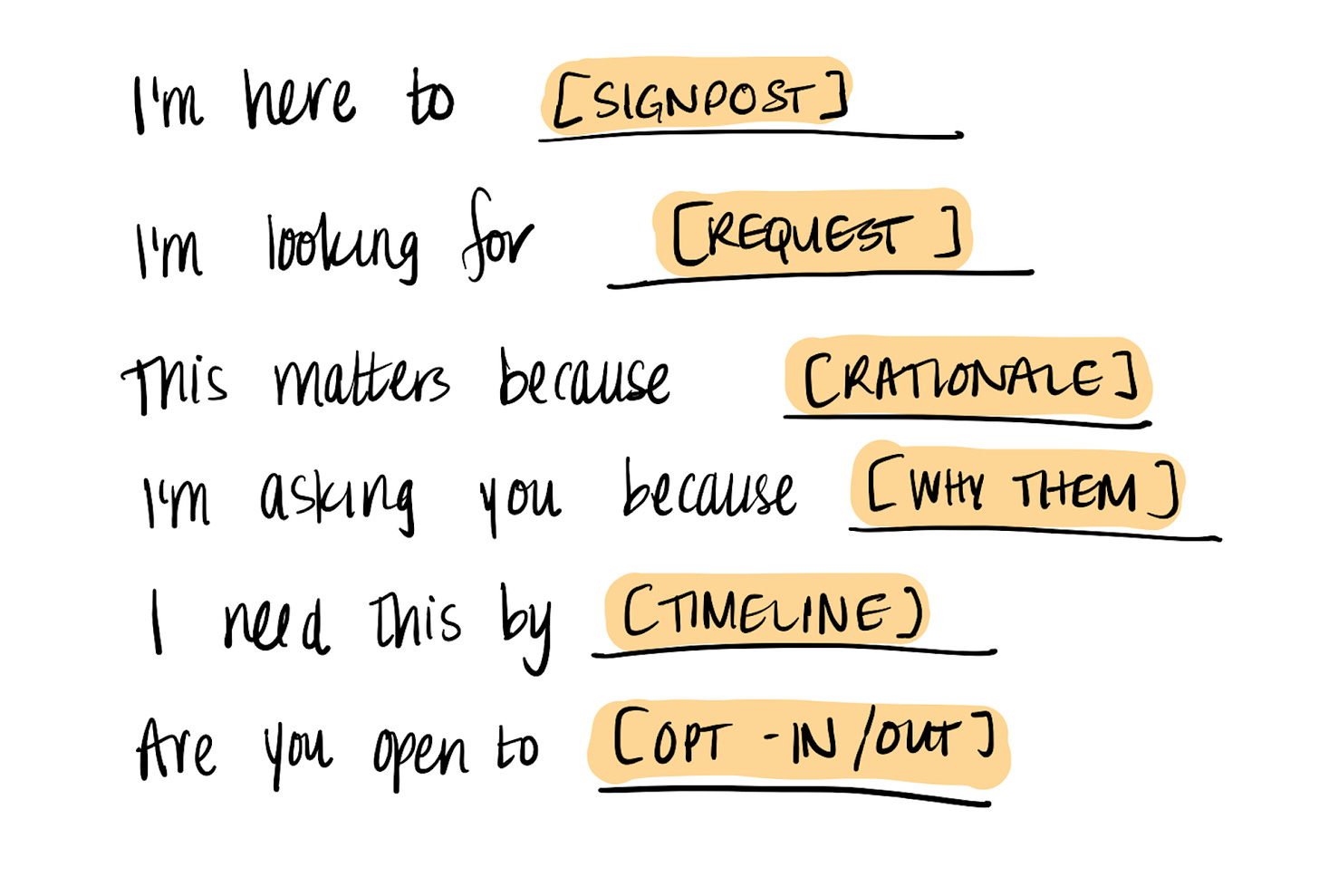

a. How to ask

Start with this template. You don’t need to use all of its parts, nor in this exact sequence, nor with these specific words. Treat it as an example, and modify it based on the strength of the connection, overlap in your goals, and expertise of the recipient.