Introducing the Foundation Sprint: From the creators of the Design Sprint

An exclusive first look at Jake Knapp and John Zeratsky’s new book, Click, and the new 2-day process for jump-starting big projects right

👋 Welcome to a 🔒 subscriber-only edition 🔒 of my weekly newsletter. Each week I tackle reader questions about building product, driving growth, and accelerating your career. For more: Lennybot | Podcast | Courses | Hiring | Swag

Everyone working in product today knows about the Design Sprint—a five-day method for teams to design, prototype, and test new products. The process goes back to 2010, when Jake Knapp came up with the steps while helping build Gmail and Google Meet. His New York Times best-selling book, Sprint, has sold over 500,000 copies, been translated into more than 20 languages, and is a staple of product team bookshelves worldwide.

I’m honored to share an exclusive excerpt from his new book, Click, the anticipated sequel to Sprint that will hit bookshelves in April. But this is not just an excerpt. Jake and his co-author John Zeratsky are sharing their new sprint method, the Foundation Sprint, for the first time ever, in this newsletter. Jake and John created the Foundation Sprint based on lessons from working with over 300 companies in the past 20 years. You’ll also learn about a framework I now encourage every founder to use—and that Jake used himself to create Google Meet: the Founding Hypothesis.

If you pre-order the book before January 31st, you’ll get instant access to a bunch of resources, including detailed guides and tools for running your own Foundation Sprint. Pre-order and claim these bonuses at TheClickBook.com.

Now, here’s your sneak preview of Click, starting with a fun story about one crazy week in Stockholm when Jake and two other Googlers co-founded Google Meet.

The Stockholm solution

In January 2009, I took a weeklong business trip to Stockholm. At the time, I was a design lead on Gmail—a job I loved—and I was in Stockholm to work on an exciting side project I’d started with two fellow Googlers. But as I walked to the Google office on that cold January morning, trudging through the miserable snow in the miserable dark, I was miserable too, because that exciting project was about to die.

My colleagues were Serge Lachapelle and Mikael Drugge. We’d met a couple of years earlier, in 2007, when Google bought their startup. The three of us started talking about an idea for a new product: video conferencing software that could run in a web browser. In those days, multi-way video calls were a hassle, so hardly anybody used them. We thought easy video calls could change the way people worked.

So we started a project to bring this idea to life. We compiled a giant slide deck. We wanted to come up with the perfect strategy to get the rest of the company excited. I became obsessed with the idea of a 3D virtual conference room, and we added more and more ideas on top of it. Interactive documents and agendas and whiteboards and on and on… But folks at Google never quite got it.

Weeks went by. Months went by. A year and a half went by. We kept improving our pitch deck, showing it to team after team, trying to make our proposal perfect.

Then the global financial crisis hit. In January 2009, Google announced it was closing its offices in Trondheim, Norway, and Lulea, Sweden. I freaked out. I figured Stockholm was next, and, if so, Serge and Mikael would be gone. And we still didn’t have a coherent strategy. It was now or never. I booked a trip to Stockholm.

So there I was, in the dark and the slush. I slogged down crooked streets until I found the Google office. I climbed the stairs of a drab gray building and found Serge and Mikael waiting for me with big smiles and a cup of hot coffee. This felt like our last chance. But what should we do?

It was do-or-die. We had one week to make people care about our idea. What would grab their attention? It wasn’t the complex bells and whistles. It wasn’t the 3D virtual conference room, or the interactive meeting tools. No, our core hypothesis was simple: We believed people would want our product because it would be the fastest and easiest video call software on the market.

So we set an audacious goal. It was Monday morning. By Friday, we agreed, we’d have a prototype of our software. Not a proposal, not a slide deck. A prototype. We would show everyone how great video calls in the browser could be with a prototype that made dead-simple multi-way video calls and nothing more.

We didn’t have time to get things perfect, so we made quick decisions. We hashed out a design that was good enough. Then Mikael, an engineering genius, built the prototype. I remember the moment he got it working. He emailed me a link. I clicked and … boom. There was Mikael. There was Serge. Mikael said hello, Serge said hello, I said hello. We could see each other!

At the end of the week, we shared our prototype, and finally—finally!—people understood. And they wanted it, immediately. Googlers started using our prototype for actual meetings, it spread across the company, and eventually the software launched to the public. Today it’s called Google Meet and has hundreds of millions of users.

The quest for the perfect start

I remember flying home from Stockholm and thinking, “Wow. That was different.” After wasting two years chasing a vague idea, we hit warp speed with a single week focused on the basics. Realization struck me—bang—like a two-by-four between the eyes: Teams need a better way to start projects.

I couldn’t get that idea out of my head. Several months later, I created the Design Sprint—my attempt to turn the magic of Stockholm into a repeatable recipe. The method took off, and guiding teams through Design Sprints became my full-time job, first at Google, then as a partner at Google Ventures, and today as co-founder of the venture fund Character Capital.

But shortly after we started Character, I noticed that, while Design Sprints are awesome for solving problems, building prototypes, and testing ideas, founders at the very beginning of big projects need more. They need a plan for standing out from the competition and they need to choose a direction for their first steps. In other words, they need the same kind of clear hypothesis that allowed Mikael, Serge, and I to cut away the fancy stuff and get to our core idea. Every team needs their own version of “the fastest and easiest video call.”

I realized this was the next stage of my quest. So I sat down with my co-founder and co-author John Zeratsky (JZ). We re-examined the most successful projects we’ve seen firsthand as designers and investors. Early in our careers, JZ and I had the good fortune to work on products like Gmail, Google Ads, and YouTube, each of which found product-market fit quickly and clicked with customers for the long haul. As partners at Google Ventures, we had a hand in smash hits like Flatiron Health, Gusto, One Medical, Blue Bottle Coffee, and Slack. We knew what they had in common, and it started with a clear hypothesis.

The Founding Hypothesis

Teams that build winning products share some fundamental traits. They know their customers—and what problem they can solve for them. They know which approach to take—and why it’s superior to the alternatives. And they know what they’re up against—and how to radically differentiate from the competition.

JZ and I call this combination of customer, approach, and differentiation a Founding Hypothesis. The Founding Hypothesis is a handy Mad Libs–style sentence that we can fill in to understand and test a team’s strategy.

Yes, the Founding Hypothesis is simple, but that’s exactly what makes it so powerful. Products click with customers when they make a compelling promise—and that promise must be simple, or customers won’t pay attention.

Every winning team JZ and I worked with made one of these simple, compelling promises. For example, when I worked on Gmail in the 2000s, our promise to customers was “We’ll solve your overflowing inbox problems better than Outlook, Hotmail, and Yahoo because we offer more storage and great search.” The promise was simple. People found it compelling, so they tried Gmail, and it delivered, so they told their friends, and so on. Today, Gmail is one of the world’s most used products. It clicked.

Looking back today, we can easily reverse engineer Gmail’s Founding Hypothesis:

In our book Sprint, we profiled several startups that built products that clicked. Again, looking back, it’s easy to identify the simple promise each one made to customers.

Here’s how the Founding Hypothesis could have looked for Blue Bottle Coffee, a startup we worked with in 2012:

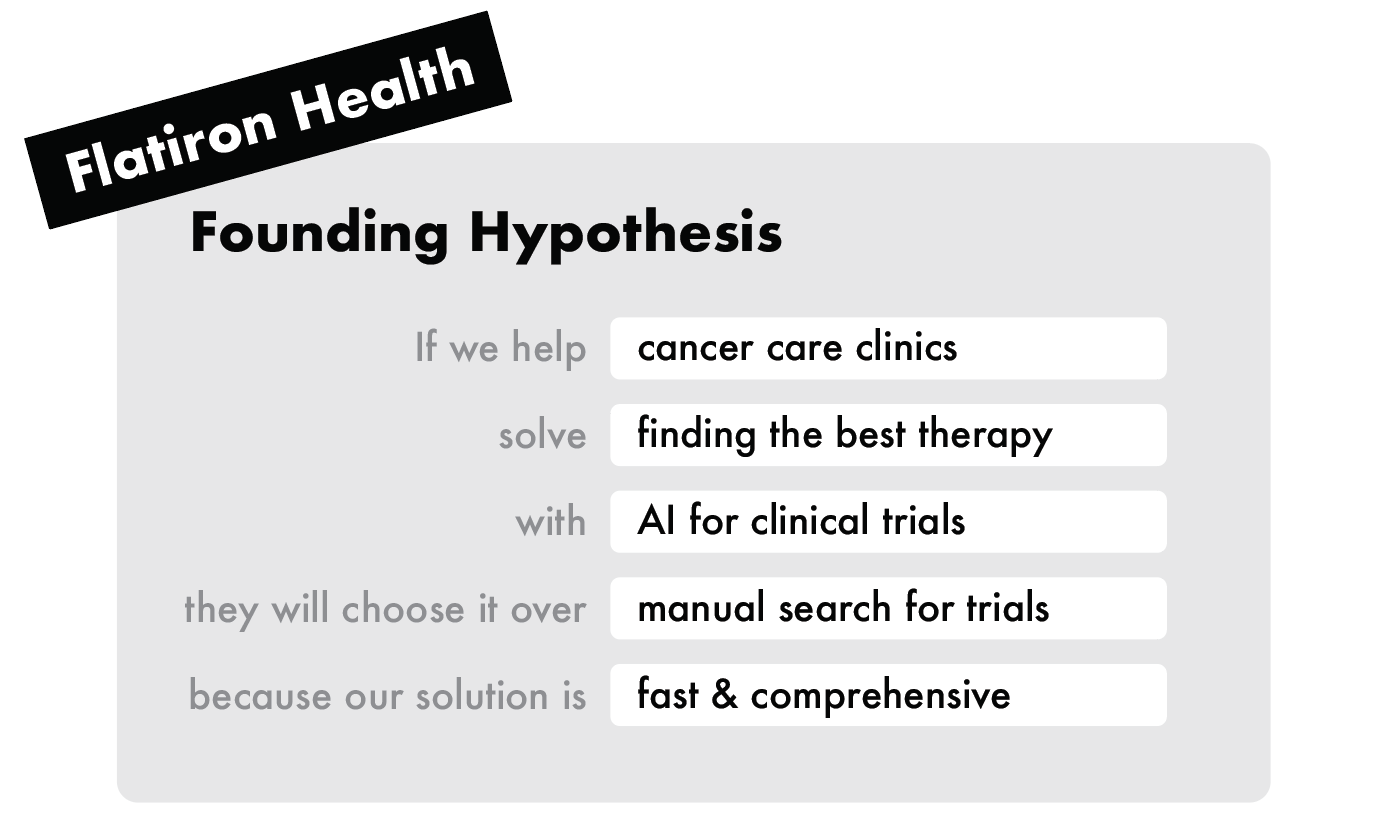

For Flatiron Health, a startup we worked with in 2014:

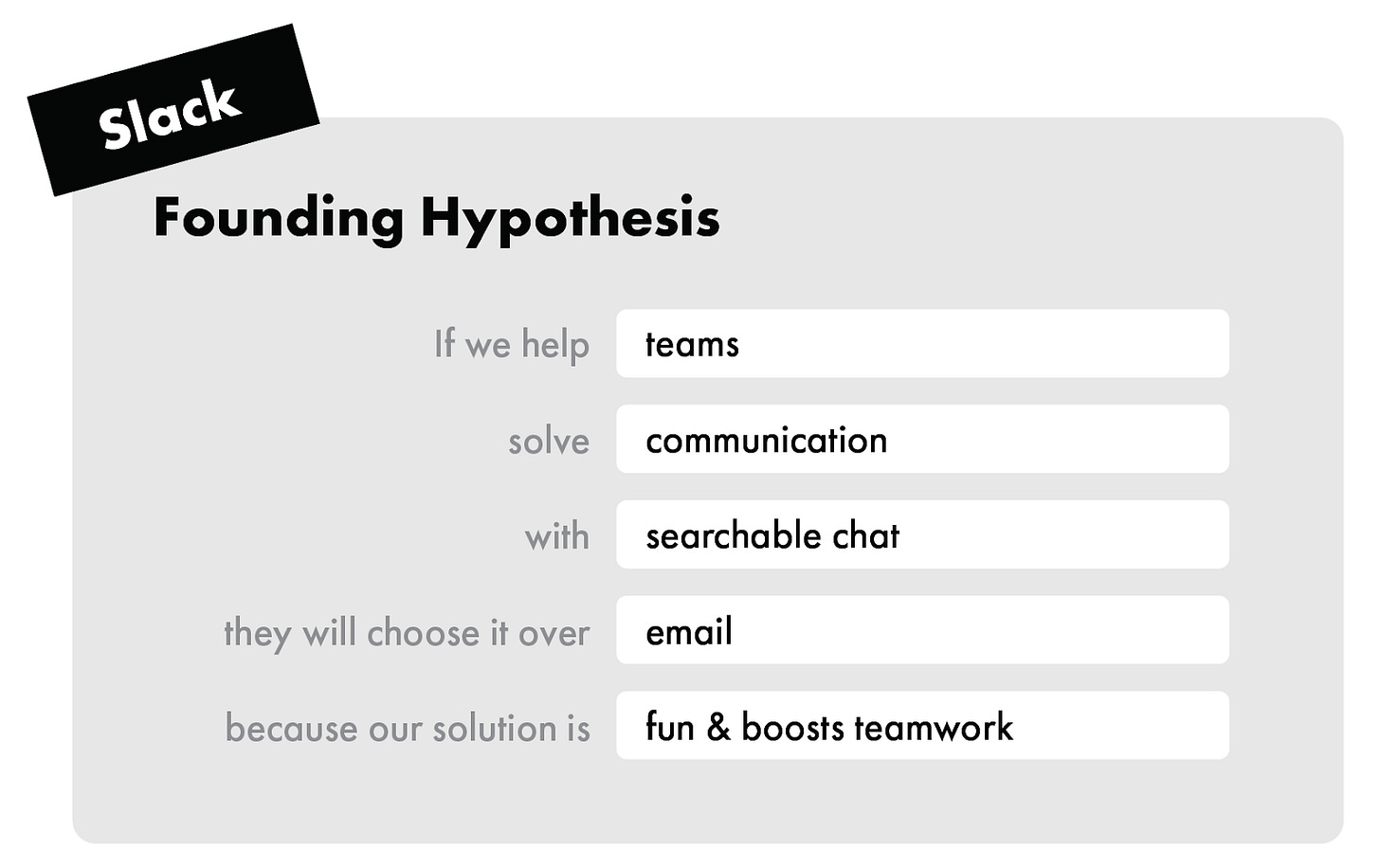

And for Slack, a startup we worked with in 2015:

Each of these startups turned into a valuable business, and each was eventually acquired for hundreds of millions, or even billions, of dollars. In each case, they made a simple promise that clicked.

Unfortunately, the simple stuff is not easy. When I first began working with startups, I was embarrassed to ask founders basic questions like “Who are your competitors?” or “How will you differentiate?” because I didn’t want to waste their time or appear naive.

But once I worked up the courage, I learned a surprising thing: If I asked three co-founders to write down their startup’s target customer, I got three different answers. If I asked a team what differentiated their product from the competition, I got a 60-minute debate. Smart, motivated people who respect their colleagues can still struggle to get on the same page. The obvious stuff is not always so obvious.

And even if a team does have a plan, there is no guarantee it will work. For every Gmail, thousands of new products fizzle. Most teams can’t find the right promise. They don’t build what people want. There are just so many ways to get it wrong.

Every big project is full of predictions, but they normally remain hidden behind the scenes. With the Founding Hypothesis, you grab those predictions, drag them onto center stage, and hit them with a dazzling spotlight. And you might not like what you see. Remember the Google Meet story? Imagine the unspoken Founding Hypothesis behind my original idea for a 3D virtual conference room:

What was I thinking? “3D aficionados”? That’s absurd! But when you shine a spotlight on a hidden hypothesis, you might not like what you see. Compare that with the hypothesis we formed in Stockholm:

The pressure in Stockholm pushed us to get real and clarify our strategy. But how can you create the best possible hypothesis if you’re not facing an existential risk, like, right now?

This is where the Foundation Sprint comes in.

The Foundation Sprint

The Foundation Sprint is a two-day workshop for a team at the beginning of a big project. On the morning of day one, you’ll define the basics of your project; then, in the afternoon, you’ll craft differentiation to help you stand out from the competition. On day two, you’ll evaluate multiple options and choose an approach to your project. By the end, you’ll have a Founding Hypothesis: a clear statement of what you believe that can be proved (or disproved) with Design Sprints.

The Foundation Sprint creates an artificial—but very effective—series of deadlines that force you to make big decisions fast. Here’s how it works:

Get ready

❏ Form a tiny team

Gather the leaders of the team: no more than five people, including the Decider (the real decision maker on the team).

❏ Block two full days on the calendar

Six hours per day provides plenty of breathing room to finish the activities and take ample breaks. Some teams will finish these activities faster, but it’s good to have the full time available to ensure you can get into deep focus mode.

❏ Stock up on supplies

You’ll need a real or virtual whiteboard, sticky notes, blank white paper, and dot stickers for voting.

Day 1

Morning: Basics

The Foundation Sprint starts with the Basics. The Basics are the so-obvious-they-get-ignored fundamentals that should inform every big decision about your project. Who, precisely, is your customer? What problem are you solving for them? What’s your advantage? Who or what are you up against? On the morning of day one, you’ll make it all crystal clear.

10:00 a.m.

❏ Choose a target customer (about 15 minutes)

Use plain language to make sure you’re talking about real people (for example, instead of “distributed enterprise orgs,” just say “teams with people in different locations”).

❏ Choose an important customer problem (about 15 minutes)

Trying a new solution will cost your customers time, energy, and/or money. What problem causes enough pain to justify that cost? What is the biggest way you can help them?

❏ Identify your advantage (about 20 minutes)

What gives you and your team an advantage over anyone else who might try to solve this problem? What capability, insight, and motivation set you far apart?

❏ List your competitors (about 20 minutes)

What options do customers have for solving the target problem? These might be other products, workarounds, or even “do nothing” (which can be a warning sign, since it indicates the problem may not be important enough to merit a solution). Be sure to identify the most challenging competitor—the 800-pound gorilla that will be most difficult for your product to beat.

Note-and-Vote for fast, smart decisions

Use our “Note-and-Vote” technique for all of the above steps, and throughout the sprint: For each question, give everyone five minutes to think in silence and write answers on separate sticky notes. Then review the answers in silence, using dot stickers to vote for the best. Finally, the Decider calls for a short debate and makes a decision (regardless of the votes).

11:30 a.m.-ish

❏ Take a break (about 30 minutes)

Get a snack or lunch. Stand up and stretch or take a walk.

Afternoon: Differentiation

Next is the crux of your hypothesis: differentiation. How can you best use your advantage? How can you reframe the decision for customers and make the 800-pound gorilla look like junk?