How Figma builds product

Yuhki Yamashita, Chief Product Officer at Figma, shares lessons learned, plug-and-play templates, and fresh insights into how Figma builds product

👋 Hey, I’m Lenny and welcome to a 🔒 subscriber-only edition 🔒 of my weekly newsletter. Each week I tackle reader questions about product, growth, working with humans, and anything else that’s stressing you out about work.

I’m kicking off a new series where I share how the most effective product teams build product. I’m often asked how to structure one’s product development process. What better way to learn than by studying best-in-class companies?

I’m excited to launch this series with Figma, one of the most innovative, interesting, and impactful product teams today. I reached out to Yuhki Yamashita, Chief Product Officer at Figma, and he very kindly agreed to answer my (many) questions. As CPO, Yuhki leads the product and design teams at Figma. Before joining Figma, he was at Uber for over four years, where he led the redesign of both the rider and driver apps. Prior to that, at Google, he was responsible for the YouTube app on iOS.

Thank you for sharing, Yuhki 🙏

How Figma builds product

1. How far out do you plan in detail, and how has that evolved over the years?

Every year, the leadership team sets high-level company priorities to frame key strategic investments. It’s then up to product teams to chart out the path to reach those goals.

A bigger planning cycle happens twice a year, with product teams revisiting their own goals and roadmaps. Halfway through each half—or in the alternating quarters—teams have an opportunity to adjust those plans based on learnings and new information.

Planning cycles haven’t changed too much over the years. They’ve been roughly quarterly in the beginning, but over time, we began formalizing things a bit more, where there was a cadence for different altitudes (annual company priorities, larger half planning, and quarterly refreshes/adjustments).

Here’s a link to our Roadmap Review Template on FigJam, which is essentially how we do planning:

I partner with Lawrence Luk (our Technical Program Manager) on leading the planning process. Lawrence comes up with the process, and together we handle the comms and implementation.

2. Do you use OKRs (e.g. objectives, key results, 70% goals, etc.) in some form?

We’ve had a fun relationship with OKRs.

When I first arrived at Figma, I actually deprecated OKRs. We had dreadful companywide OKR meetings where we went through a spreadsheet tracker of hundreds of OKRs that were really more like tasks assigned to individual contributors. While it was good at creating some level of accountability, it was hard to understand why any of this mattered.

I asked teams to instead define headlines—essentially, claims that they’d like to make by the end of some time period. For example, it might be something like “Figma is the most efficient way to design,” and the team offers both quantitative and qualitative ways to evaluate that claim.

This helped me understand what a team was philosophically going for. It produced the right debates, and it allowed teams to be a bit more creative around how to measure whether they’ve achieved that headline (e.g. a combination of a variety of metrics and qualitative signals). It recognized the reality that some things, like the core experience of Figma, are hard to measure and can’t be reduced to a single metric; it gave room for teams to invest in a roadmap of exploring different KPIs versus artificially elevating a metric that ultimately people didn’t believe actually mattered.

Once we hired a data-science leader, we brought OKRs back and have iterated on this format a bit. In some areas, we’ve become more sophisticated with metrics. In other areas, they still can be a bit more qualitative. Importantly, we’ve tried to keep constructs that allow for us to check on the philosophical alignment. And we’ve played around with branding OKRs more as a “commitment” to make sure that teams actually felt responsible for achieving these goals (versus it just feeling like the technical measurement of success but not something teams are indexed on day-to-day).

Our OKR process is actually run on FigJam. We have teams write “commitments” (our rebranded OKRs) in these widgets that Lawrence made:

3. How do your product/design review meetings work?

We have design crits and product reviews.

Design crits are intended to be very generative, and are explicitly not about making decisions. Designers share a file (often on FigJam), and we spend 10 minutes heads-down silently leaving stickies and comments to give feedback on the designs before discussing live.

Product reviews are more about making decisions and debating directions. Here’s our template. We have different kinds: ones where we’re trying to align on the problem or ones where we’re trying to align on the solution. One thing I encourage for both is to first present the “option space”—it’s really powerful to have a framework that maps all possible solutions or problems and use that as a device to discuss high-level tradeoffs or philosophical differences.

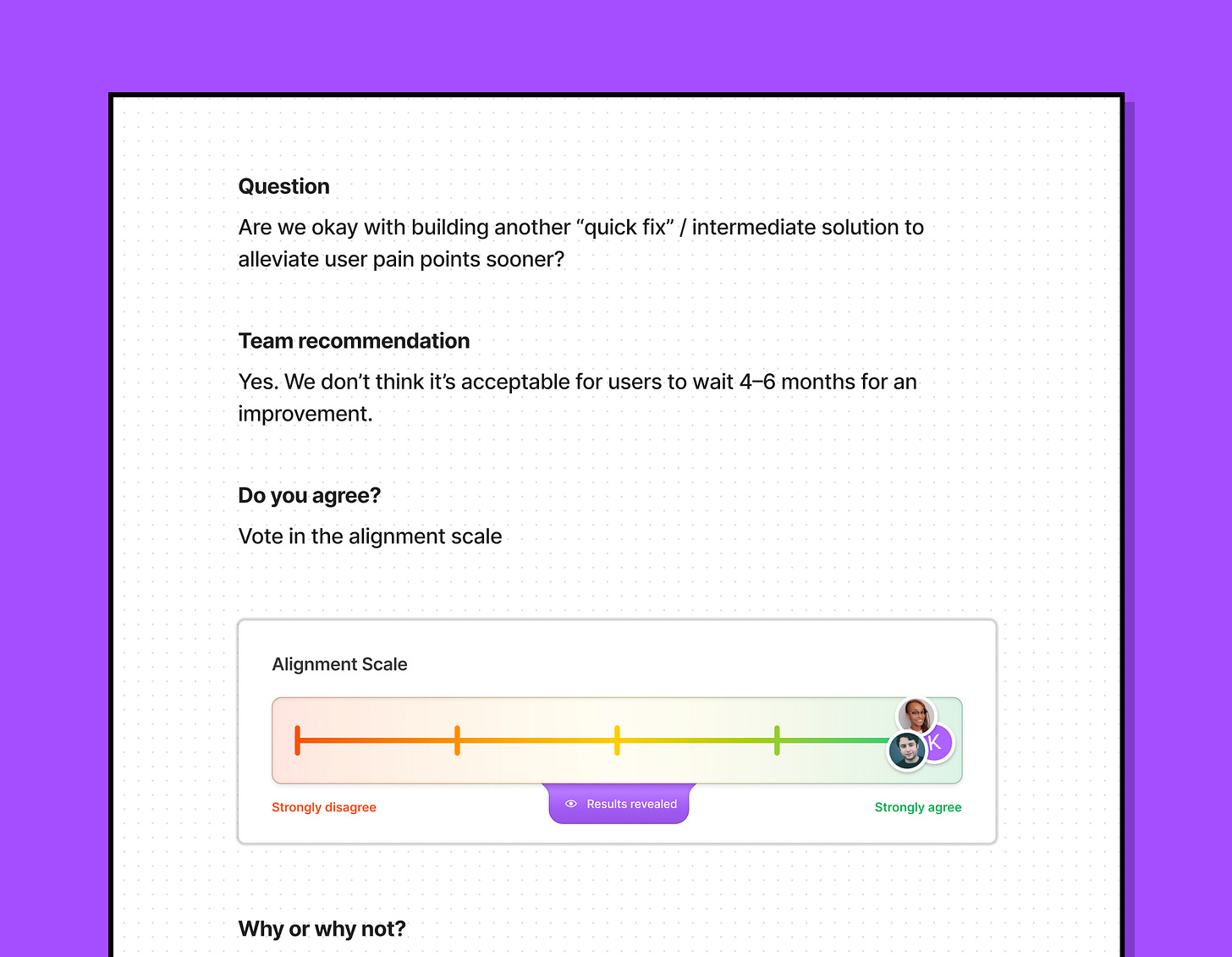

It’s been interesting to see the evolution of the format. When I arrived, people were projecting docs and there was more of a memo culture. I switched this format to decks, mostly because I wanted to push for more of a storytelling culture (and also so my PMs can use Figma more!). And recently we’ve been using FigJam more, because it allows for more of a two-way conversation and it’s easier to gauge people’s reactions. My favorite is adding the alignment widget, which lets people share/vote on their sentiments toward specific decisions; I find this so much more powerful than allowing the loudest people in the room to dictate the outcome!

4. For design crits, who comes to these meetings, who runs the meeting, and how often do you meet?

Crits are a central part of our design culture at Figma. We have five standing slots each week, and attendance increases in size with each session over the week (e.g. Tuesdays are for tech pillars, Thursdays for Editor and Non-Editor teams, and Fridays are for all of design).

Designers have control over booking them and inviting any additional teammates (beyond the pillars or teams already in attendance). We send out an automated reminder each week in Slack for sign-ups.

For the larger crits, we also welcome guest “observers” from across the company. We believe it’s important for everyone to see how designers share ideas and offer feedback on projects. We encourage every employee to attend at least one crit per year, regardless of their role or position.

Our crits are fairly structured, following a similar format and led by the presenting designer. Typically we get to two topics per meeting, with a rough agenda of:

~10-15 minutes of presenting (we use Spotlight in FigJam, and attendees are welcome to comment while someone is presenting)

~5 minutes of lingering questions

~5 minutes of silent writing and commenting on the file

We find that this format gives presenters a greater breadth of feedback, while offering a few different entry points for attendees.

For more about crits, our Vice President of Design Noah Levin wrote about our process here.

5. For product reviews, same question.

These include all of product leadership, including Dylan Field, our CEO; project leads; and key decision makers. They happen somewhat ad hoc, but generally at critical milestones in a product’s lifecycle, and are typically facilitated by the PM whose product or work is being reviewed.

6. How many PMs do you have?

Twenty-two, and we’re hiring!

7. Do you structure your product teams around products, user types, user journey, outcomes, or something in between? Has this changed over the years?

This is also a fun debate!

Right now, we organize around products and platforms. We have two products—Figma Design and FigJam—so we have two teams solely focused on the respective product. We then have “horizontal” platform teams that build features and solve problems across both products, e.g. the “Enterprise” group that focuses on making both of these products amazing for large enterprises and the “Infrastructure” group that ensures the reliability and performance of both products.

This has changed a bit over the years, especially when we were a single-product company. At the time, teams were organized more around product surfaces (which roughly corresponded to use cases).

Solving team structure is an art, not a science, and something that we expect to revisit continually as we grow.