How Coda builds product

Lane Shackleton, CPO at Coda, shares his team’s templates, day-to-day processes, and hard-earned lessons

👋 Hey, I’m Lenny, and welcome to a 🔒 subscriber-only edition 🔒 of my weekly newsletter. Each week I tackle reader questions about building product, driving growth, and accelerating your career.

I’m often asked how to best set up a product development process, and since I’ve only had first-hand experience with a few approaches, I’ve embarked on an ongoing series to learn how the best product teams build product. Part one was on Figma (which quickly became my fourth-most-read post of all time), and today I’m excited to bring you a deep dive into Coda’s unique approach to product.

Having spoken with many PMs from Coda over the years, plus having Coda’s CEO, Shishir Mehrotra, on my podcast, I’ve always seen Coda as an incredibly thoughtful, deliberate, first-principled product culture. After digging into their approach, this proved to be absolutely true. I’ve never seen a product development process this well-thought-out and executed.

A big thank-you to Lane Shackleton, the CPO at Coda, for sitting down with me and answering all of my (very detailed) questions—and also for sharing a dozen plug-and-play templates 🤯

Enjoy!

How Coda builds product

1. How far out do you plan in detail, and how has that evolved over the years?

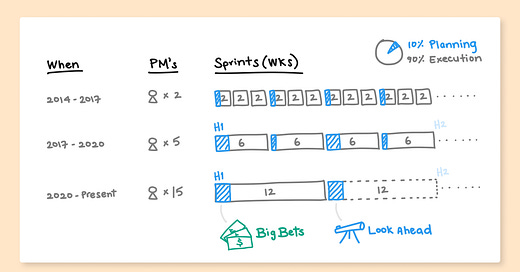

The planning motion you need to build a nascent product with few customers is quite different from that of a more developed product with lots of established customers. As we progressed along that journey over the past seven years, the way we plan evolved a lot.

As a general rule, though, our view is that planning should take up no more than 10% of the execution time period. So if you’re planning for a quarter, your planning period should be slightly less than nine days.

In the early days, we started with two-week sprints. We’d get small teams together, and they’d run a daily standup to figure out what to accomplish that day. The two-week sprints felt fast and like the team was on the hook to deliver a lot of product and learning in a short span. Then, every three sprints (or six weeks), we’d pop our heads up and do a check-in. The six-week check-ins provided a good moment to reflect on what we learned, improve our team’s rituals, and quickly plan for the next two weeks. The team was composed of two or three PMs and 10 to 15 engineers during this period.

Later, the company grew to roughly 30 engineers and four or five PMs. By this time, we had beta customers that the team was working closely with, and the shape of the product was more known. The two-week sprints started to feel a little frantic, and we felt the need to create space to strategize on the longer arc of what we wanted to accomplish. At that time, we moved to six-week sprints, along with H1 and H2 planning. During H1 (first half of the year) and H2 (second half of the year) planning, we made the space we needed to do more long-term strategy work for the company. At the same time, six-week sprints felt like the right window for running fast against specific commitments where we had confidence or something specific we wanted to learn.

For the past two years or so, with a PM team of 12 to 15, we do what I call “Quarterly Plus” planning. We couple that with our annual Big Bets. We start with Big Bets, and those ladder into Quarterly Plus planning (more on this below).

To arrive at Big Bets, we use a strategy process that is inspired by one of my favorite strategy books, called Good Strategy Bad Strategy. One of the core ideas behind the book is that good strategy is an answer to a specific challenge. So we start our annual planning by reviewing our best insights from our Customers team and Data and Insights team with the goal of determining the most important challenges to address. As a group, we enumerate and rank the key challenges facing the business. Then smaller groups of leaders develop strategies against those key challenges, and the group reviews them together. We run a few $100 voting exercises to get a pulse on where we may have some alignment versus not, then we debate further and ultimately decide. By the end of the process, we have a small set of Big Bets.

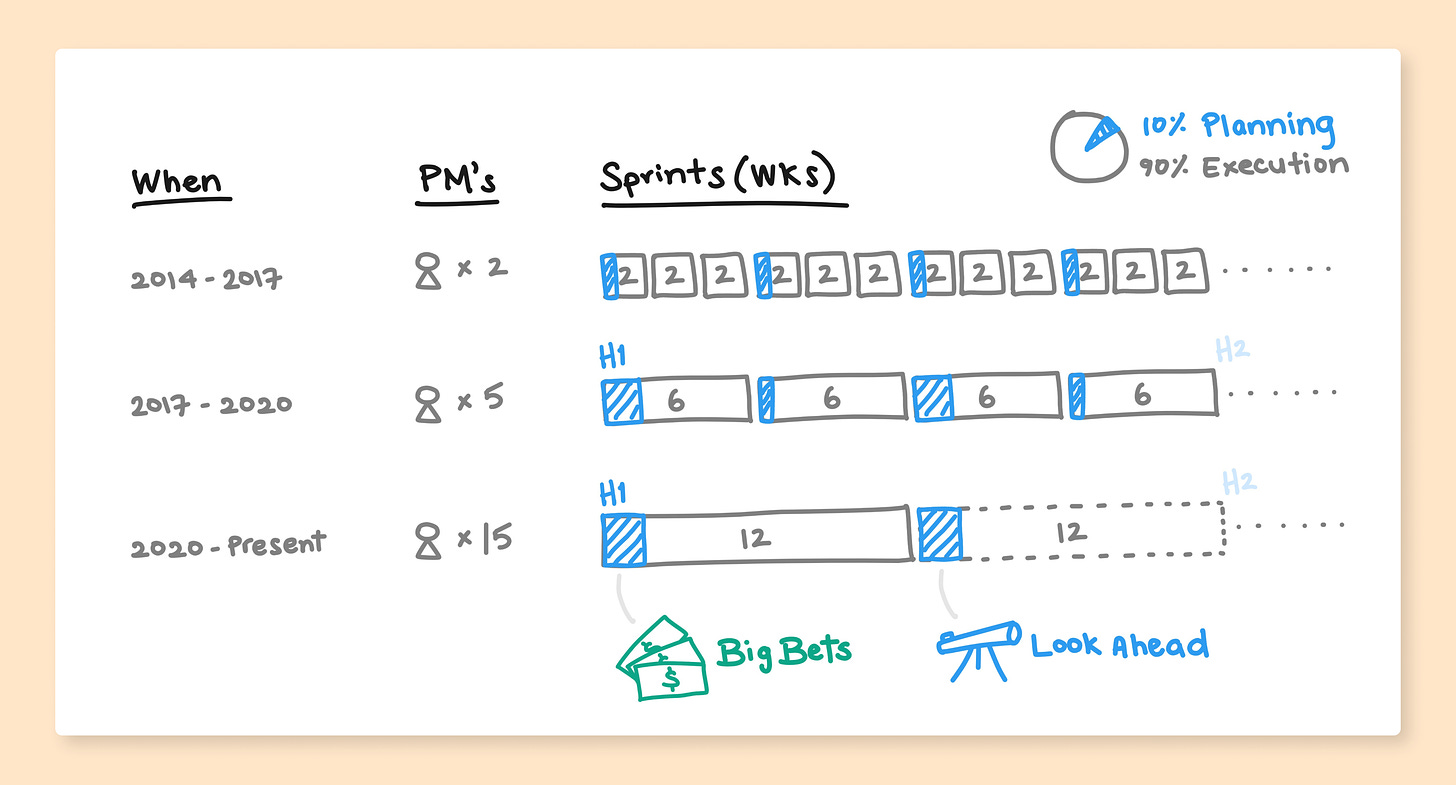

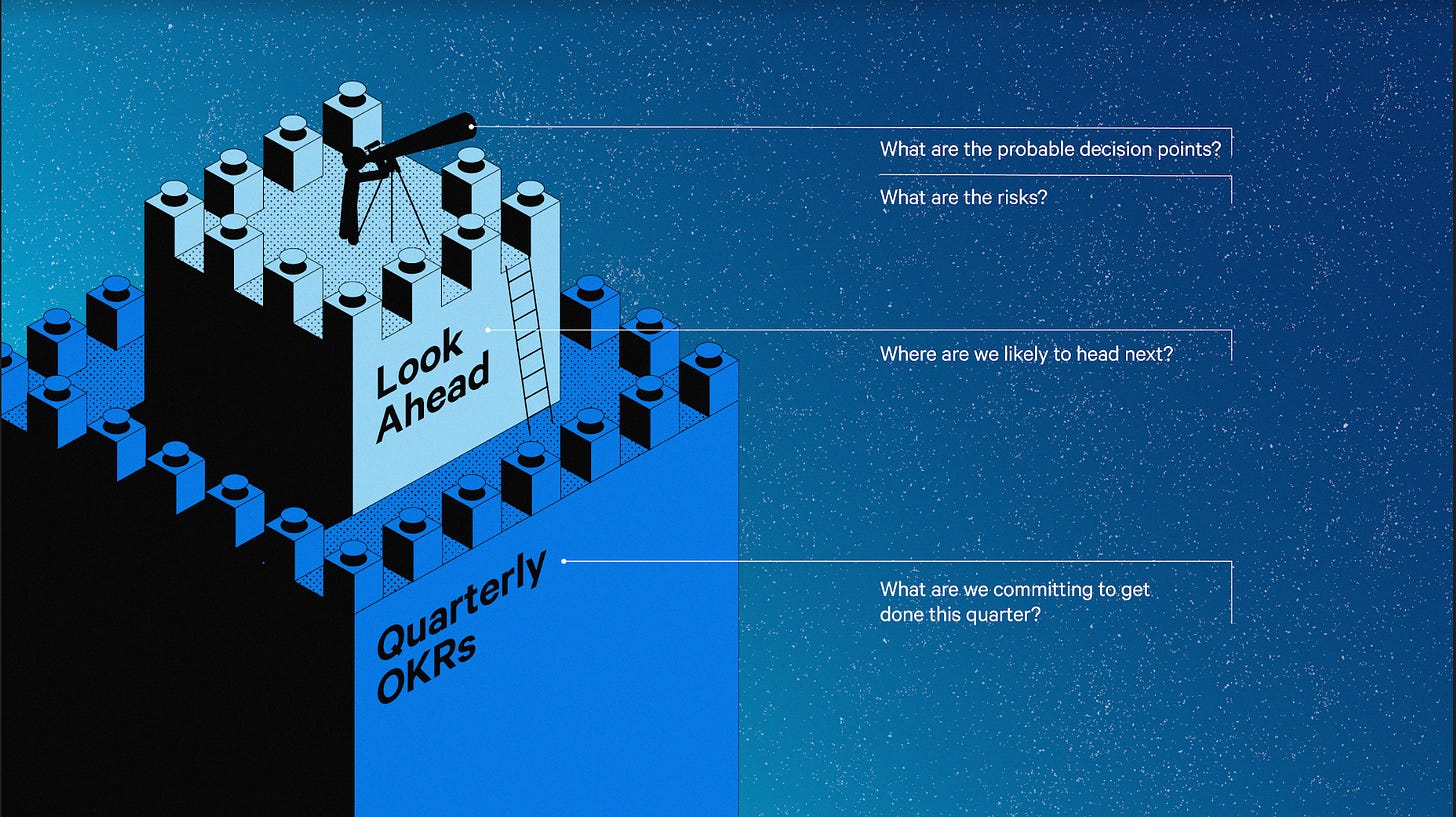

Our Big Bets serve as the foundation for team-level quarterly planning. We ask teams to plan concrete commitments for what they will get done, then provide a look ahead to what’s coming the next quarter—hence, Quarterly Plus. The observation is that it’s very hard to plan six months out in a scenario where you’re learning week to week. But you often have a sense of where you’re headed, what the probable decision points are, and what risks lie ahead. So while it’s not a committed plan, it gives the team and the broader company a look at the longer arc and helps them contextualize your current quarter’s OKRs.

I love the creativity our teams bring to this exercise. We commonly see fun patterns of reactions where the teams will intersperse things like heart, question, clap, question reactions in the text of their writeup to get the reader engaged and provide lightweight feedback. Oh, and one team is notorious for including catchy songs about their goals. Last year, this team rewrote the lyrics of “Hooked on a Feeling” to turn their OKR presentation into a memorable music video. Sometimes we’ll even replay it during meetings just for fun. :)

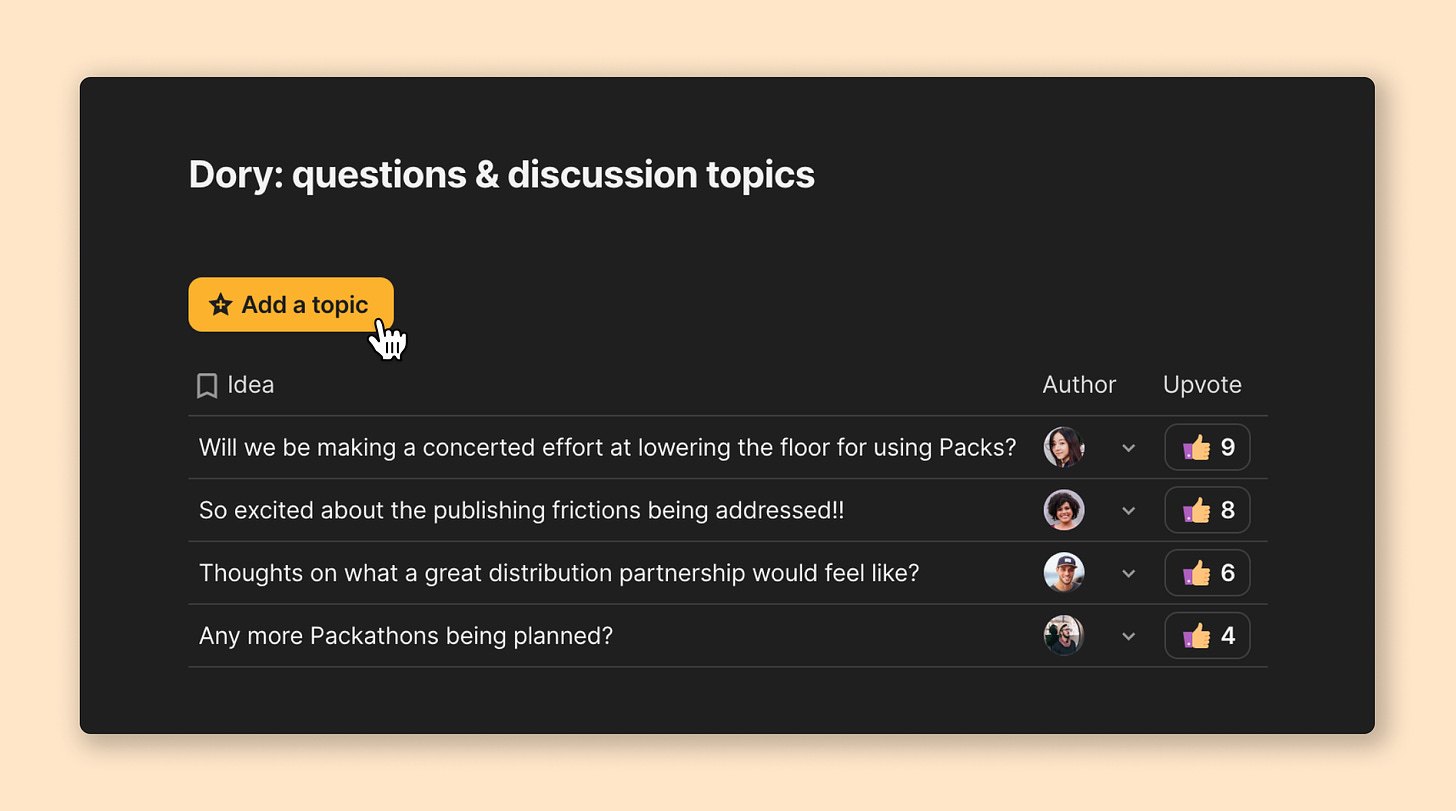

The artifact that gets produced is a two-pager, in two-way writeup style, with two classic Coda rituals: a pulse for gathering sentiment and Dory for asking questions (named after the fish in Finding Nemo who asks all the questions). You can see how it looks below, and here’s a real example from a product discussion. Here’s also a template, or just type /dory and pulse in any Coda doc.

Stepping back, the main drivers of increasing the cycle times, and thus forcing us to plan further out, were:

Customers—As we spent more time with more customers, we developed a better understanding and more certainty that we were solving the right customer problems. In turn, this understanding enabled us to think further ahead.

Product—As the product matured and PDE challenges became better-known to our teams.

Strategy cadence—As the company grew, the feeling of when and how to have deeper strategy conversations changed. When we were small and in the same office, we’d have deep strategy conversations over lunch. As we started to have larger groups across offices, teams needed to be grounded in longer-term plans and naturally accepted less ambiguity.

Decentralization—As teams got bigger, it made less sense to plan in a centralized way. Initially, the Product, Design, and Engineering leads centralized prioritization stack ranking. As it became more bottom-up and decentralized, we needed to plan further out. Overall, I’m a big believer in decentralized leadership and giving teams autonomy to solve problems.

Dependencies—An increasing number of dependencies across teams, though we always try to minimize the need for these.

2. Do you use OKRs (e.g. objectives, key results, 70% goals, etc.) in some form?

Yes, though we’re always tweaking and evolving our approach to them.

Importantly, we make it clear that OKRs are not a strategy. Strategy planning happens independent of OKR planning. I think it’s very easy to fall into the trap where OKRs seem like a reasonable replacement for a strategy doc or presentation that describes the broader challenges you’re addressing with a clear why and how.

When it comes to OKRs, we throw out the piece about 70% of hitting your goal being considered success. I believe this is a luxury you have when there is a money-printing machine in your basement (like Google, where I worked for nine years). Instead, we goal around getting to 100% of our commitments. Obviously we don’t always hit 100% of our OKRs in practice, but the expectation is that you’ve set the OKR because you believe you can deliver on it. Of course, we let people defer or carry over an OKR to the next quarter, or explain why we’ve learned something new that caused us to rewrite or remove it.

On the metrics side of OKRs, we try to ensure that teams are distinguishing between “input” and “output” metrics. I find these often get confused. For example, someone might say, “It’s so hard to move activation in OKRs.” But that’s because it’s a lagging output metric, influenced by lots of different inputs, which rarely changes in a single quarter. So we want teams to goal themselves around metrics they have control over. If the team has control over the metric, the question becomes more tractable: Do we believe the input metric will move the output metric?

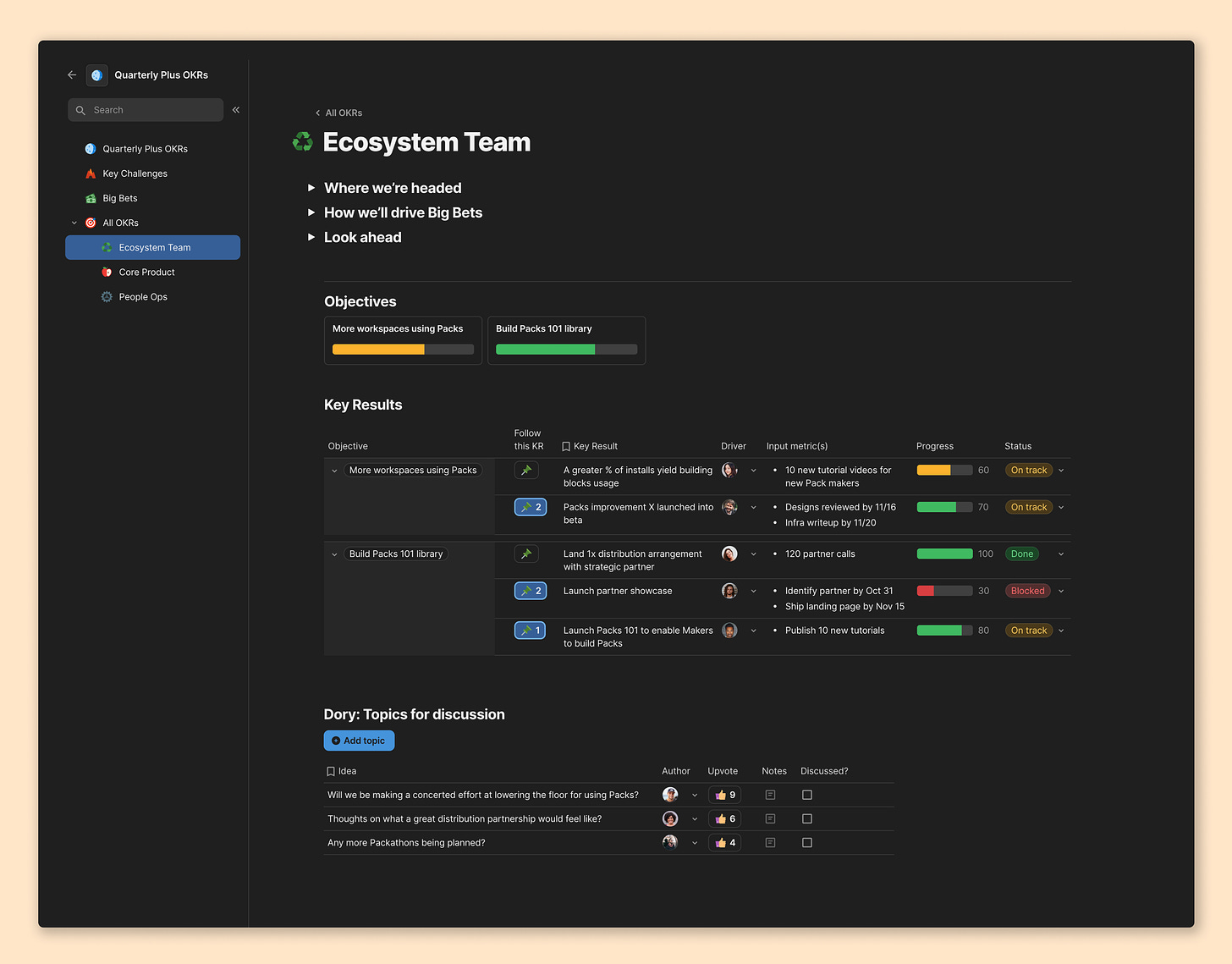

At the end of the planning process, teams present an OKR writeup that describes where they are headed and why it matters to our Big Bets, and include a brief look ahead at the next quarter. Then we embed their OKRs as a table within that writeup. I find this makes it much easier to understand the why behind the detailed rows of OKRs you’re seeing. We also put a Dory at the bottom of these writeups so that anyone can ask any question. For years, we’d review these in a central OKR review meeting, but these days we have people ask and answer questions asynchronously.

Here’s a sanitized example of what that feels like for one of our teams, the “Ecosystem Team.”

3. How do your product/design review meetings work?

We strongly believe in autonomy for each team, and so our approach to product and design review meetings trickles down from that. There are two main review forums where product and design work is reviewed: Catalyst and Design Huddle.

The forum we call Catalyst starts from a few hard-earned lessons from years of running review forums. Most review forums have common problems like not having the right people, or not starting with the right context, or being bulldozed by a senior leader. So we designed Catalyst to solve for some of the problems we’ve observed in past companies.

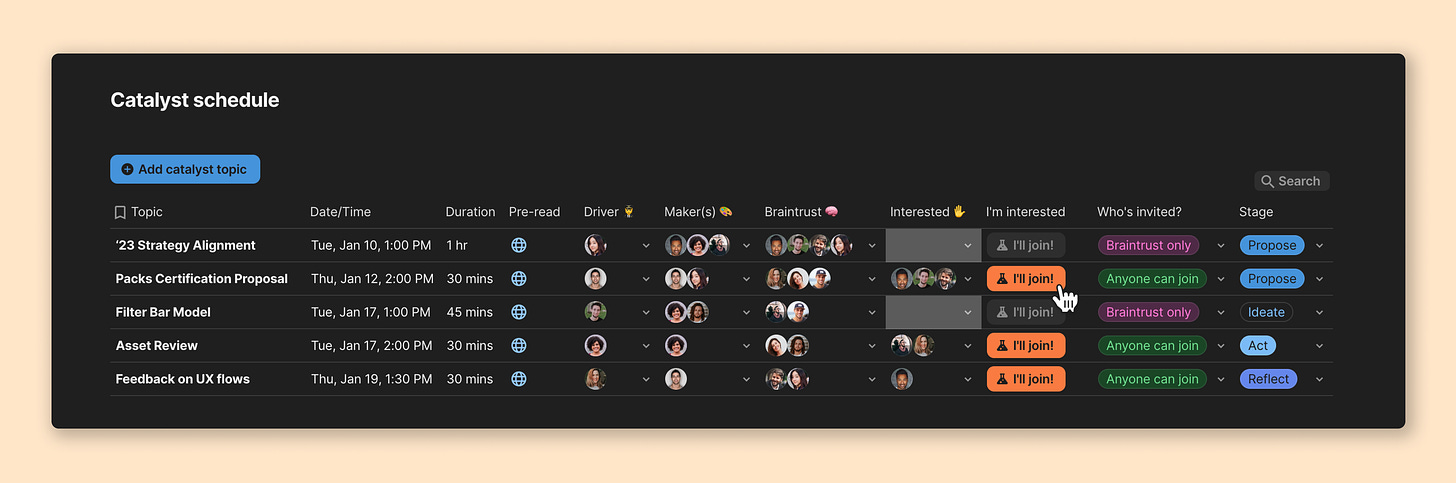

It’s an hour block on the calendar, three times per week at 1 p.m. PT. The foundation is having three hours per week where you can get anyone in the company to review and provide feedback on any type of plans, including product. Anyone can sign up for a Catalyst slot, but we’ve evolved some very clear roles:

Driver: runs the meeting and facilitates the decision-making process; often the PM

Makers: the “doers” who will be executing on the results of the meeting

Braintrust: pulled in to guide and provide context for the Makers; often other leaders

Interested: people who want to follow along on the topic

Below is our Catalyst schedule, with the option to join as “Interested.” If you’re a Driver, Maker, or Braintrust, it gets auto-added to your calendar by the doc.

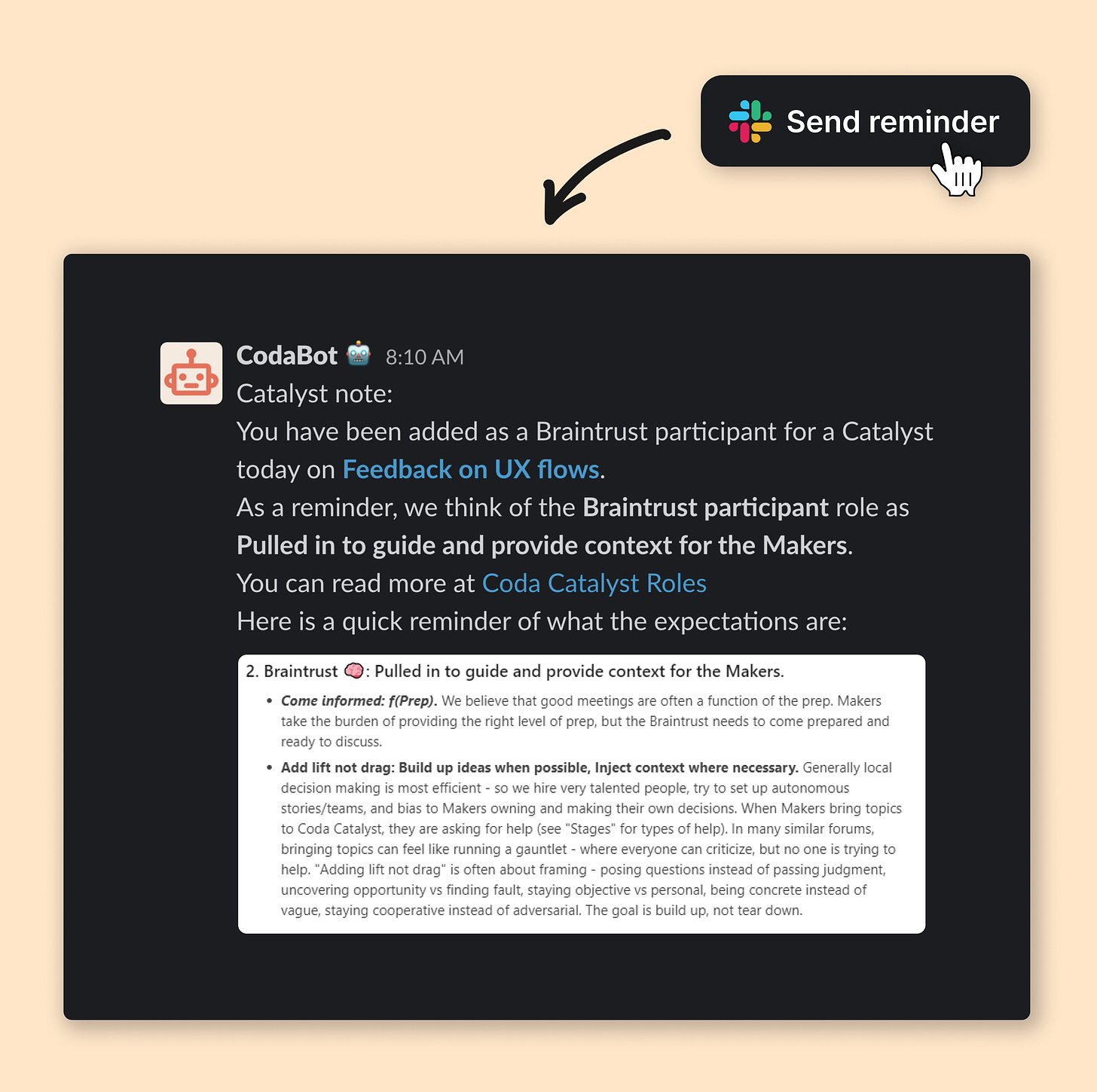

One little detail I love is the automated reminder that the doc sends the day before reviews. It’s a Slack message that tells you the topic and the links you need to review and reminds you of the expectations of your role in the meeting. The descriptions include some of my favorite reminders for people in review forums, like “Add lift, not drag,” with a clear description of what that means.

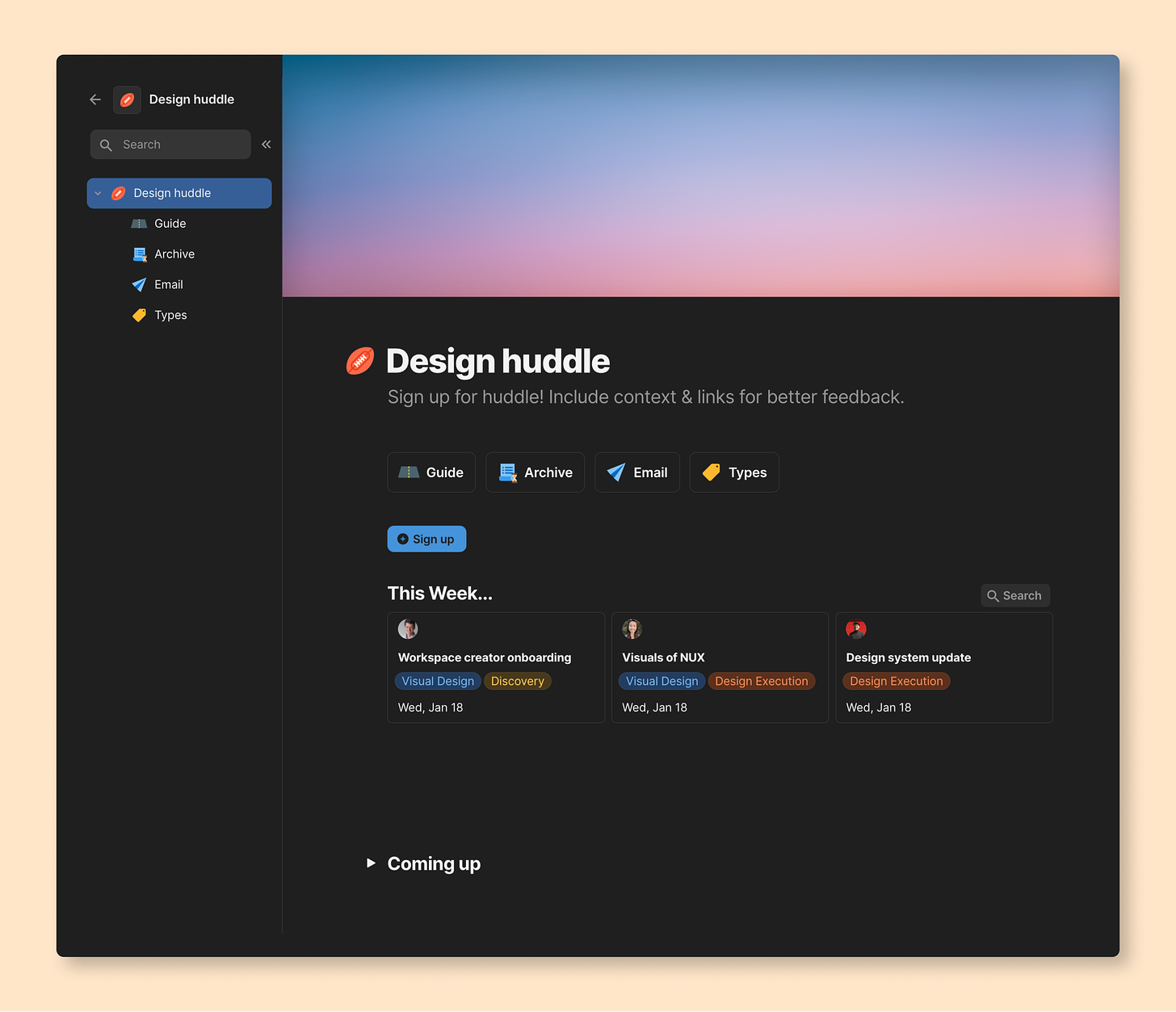

The other review meeting is called Design Huddle. It’s a once-per-week forum where designers can bring work at any stage for feedback. A Slack notification goes out from the doc the day before, reminding people to sign up. Designers specify the topics, the project phase, the time they need, and the type of feedback they are looking for. We usually get to two to four topics from various designers per meeting, in a round-robin style. We also encourage designers to invite their PM partners so that they get to hear the feedback directly too.

In the meeting, the group usually jumps into Figma and follows the designer around the file, adding comments, riffing, and reflecting on the work.

In addition, as we’ve grown, individual teams will have their own Design Huddles or Design Jams. For example, our Core Product team is our largest Design and Product team, so they have a Design Huddle specific to their area. Designers choose which audiences are most appropriate given the topic.

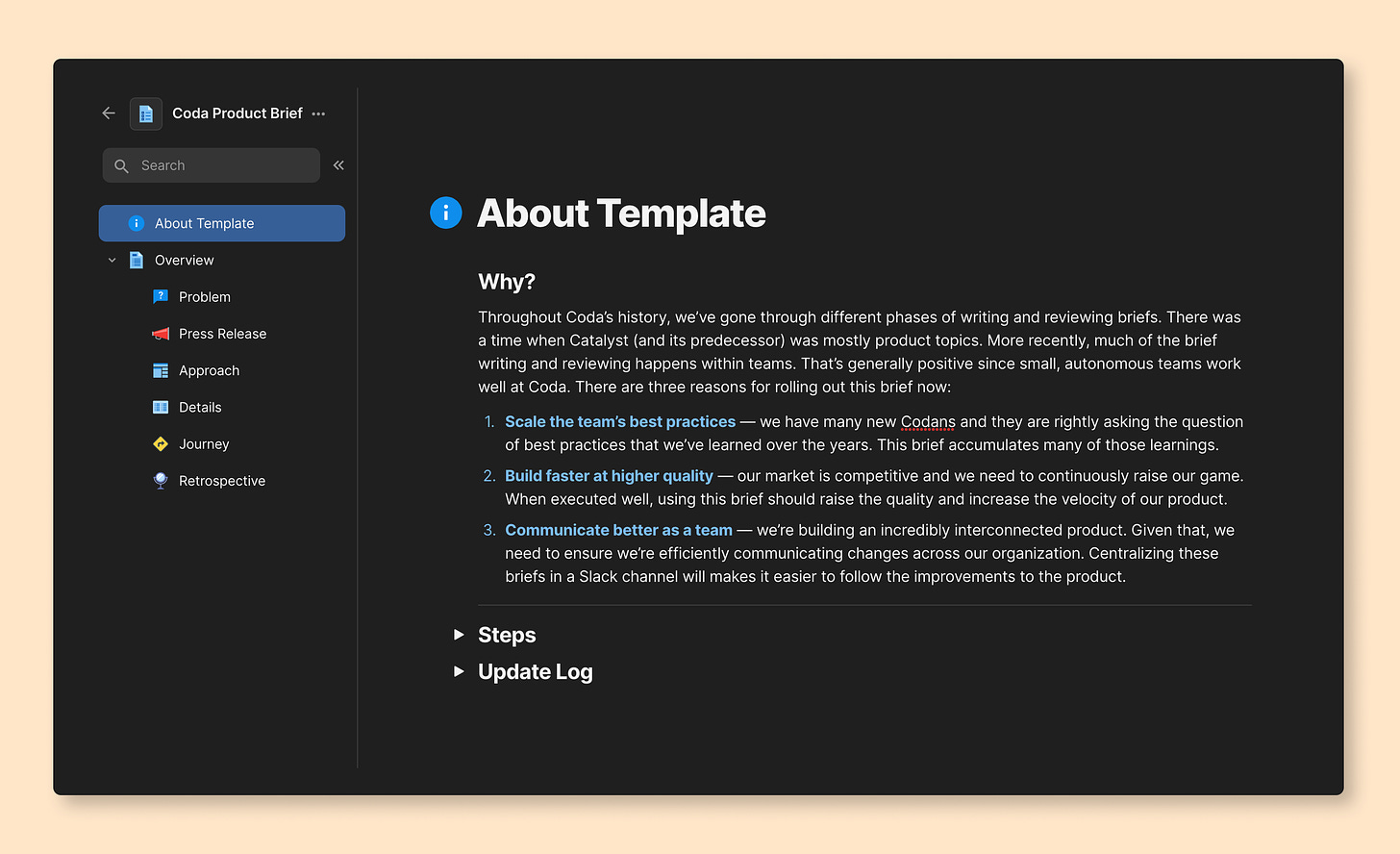

In addition to the meetings listed above, a lot of our product and design work is done asynchronously through docs. It gives teams a way to clearly document their ideas and get fast feedback. One core example is our product brief. We list out a few high-level stages that most projects go through (below).

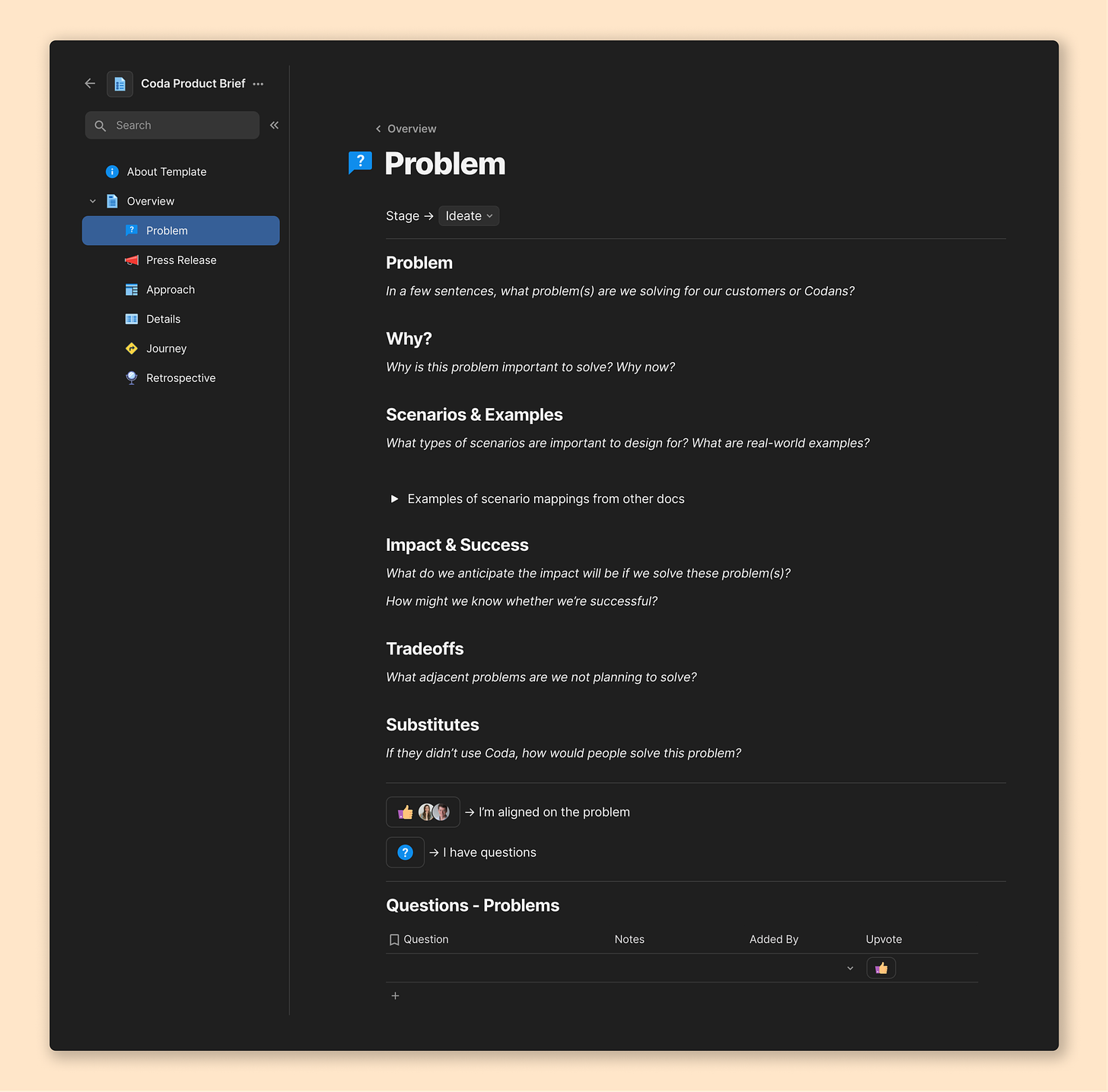

Problem—articulating the problem and how it’s experienced by customers.

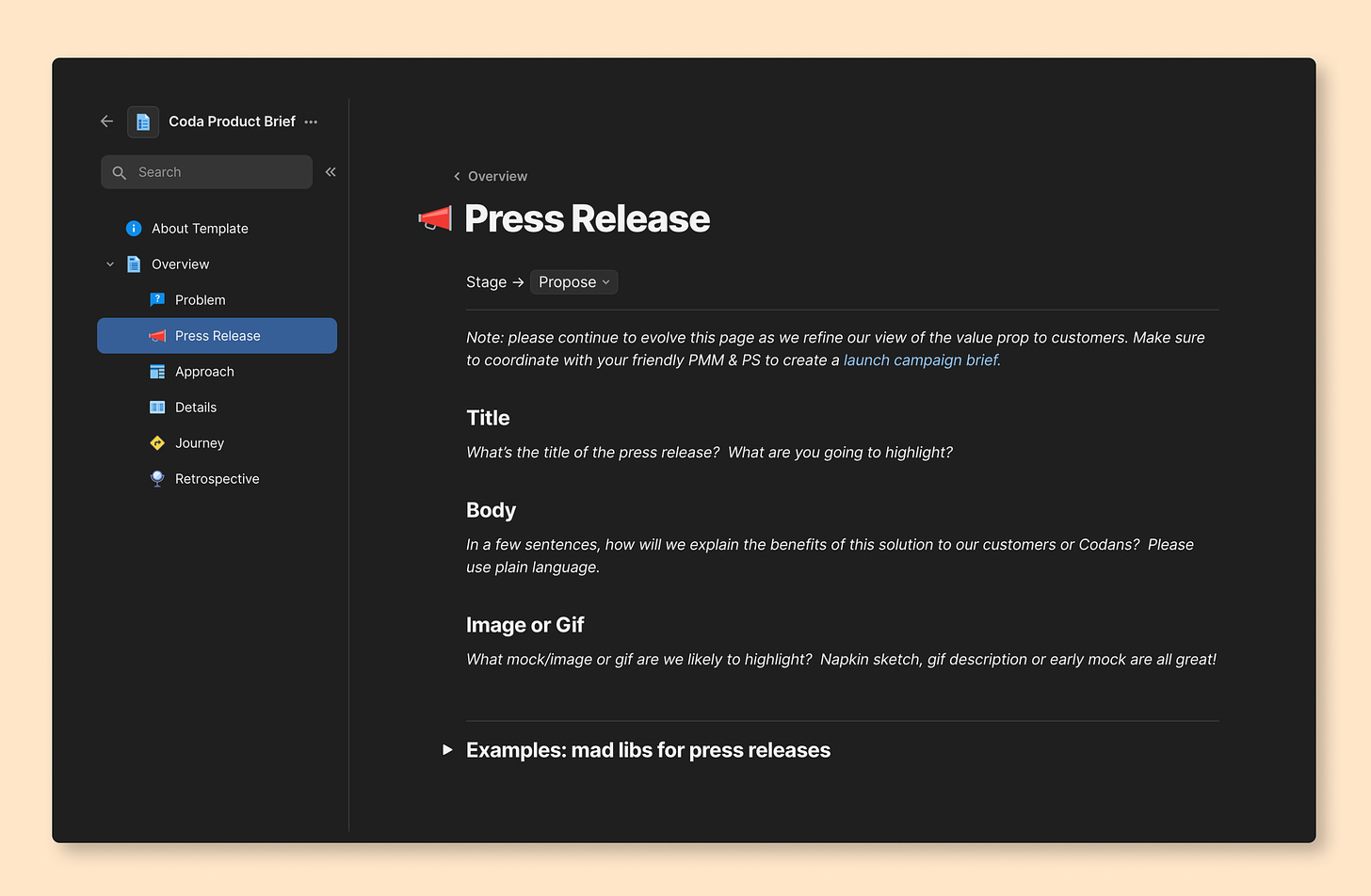

Press release—articulating how we’ll describe the value to customers and aligning on this early.

Approach—describing the high-level approach we may take and gathering early feedback.

Details—describing detailed decisions, tradeoffs, and open questions.

Journey—walking through the customer experience and how our decisions feel in practice.

Retrospective—reflecting on the effort, what we learned, and what we’ll do next.

Teams may use parts of the brief or the whole thing depending on the size of the effort involved. The asynchronous reviews or meetings tend to focus on one of these stages at a time. So for example, we may have a Catalyst meeting that is focused on aligning on the overall approach.

Most efforts start with a problem brief. Here’s the intro to the Product Brief template that sets context:

Here’s our problem page of the brief as an example of how each page is structured:

We sometimes also write a press release. I find that teams can quickly explore broad directions simply by writing two or three versions of a press release. It forces us all to do two things. First, we can read the problem statement and the press release and make sure these things align. Second, as a group, we can get clear on the value we think we’re delivering to customers early in the process.

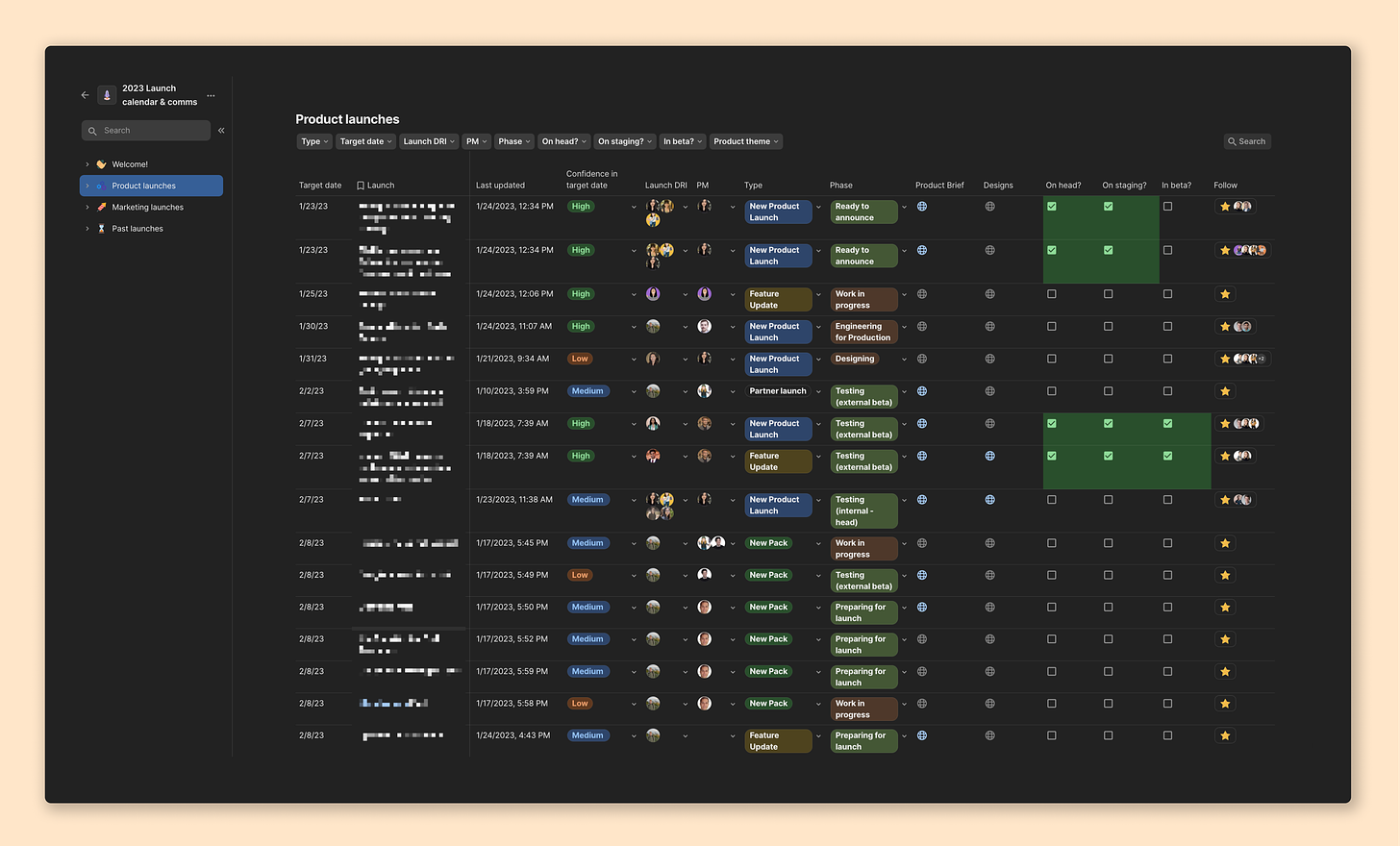

And finally, if you want to look across all upcoming launches, we have a centralized launch calendar. One thing we noticed early in Coda’s history is that we should have a central source of truth for anything that is going out to customers. So it includes a mix of new features, improvements, partner launches, and even email campaigns and blog posts. It’s a highly customized version of tools we’ve seen in other companies, like Google’s LaunchCal. The doc has lots of automations that send reminders to individuals so that they keep the details of their launches up to date. It’s one doc that is always open in my browser. :)

Below is a look at our real launch calendar with the actual launches blurred out. We make lots of different views of this table, customized to the needs of different teams. My favorite email every week is a summary that gets sent from this doc of past and upcoming launches.

4. Who do PMs report to, ultimately? And are product and design part of the same org? Has this changed over the years?

We have a joint Product and Design team. PMs report to PM leads, and PM and Design leads report to me. I report to Shishir, the CEO.

The joint team is based on an observation from Google and YouTube.