How a traumatic brain injury made me a better PM—and person

Takeaways from a period of extreme adversity

👋 Hey, Lenny here! Welcome this month’s ✨ free edition ✨ of Lenny’s Newsletter. Each week I tackle reader questions about building product, driving growth, and accelerating your career.

If you’re getting this post, that means my wife’s due date is very near (😮💨), or our kid was just born (🥹). To give my new family my undivided attention, I’ll be taking a month or so of parental leave. To make sure you continue to receive exceptional value from the newsletter during this period, a few months back I put out a call for guest posts. Out of 500+ pitches, I whittled it down to six extraordinary posts. Today’s post is the first of the series and comes from Amol Avasare, who runs B2B growth at MasterClass. Amol was previously an investment banker, chief of staff, and a founder, and last year Amol suffered a serious brain injury. His story of recovery has stuck with me ever since I read the first draft. Enjoy ✨

For more from Amol, make sure to follow him on LinkedIn and Twitter. He also writes a great newsletter, Time to Ship, which is a daily digest of the latest features shipped by your favorite product teams.

“The real troubles in your life are apt to be things that never crossed your worried mind—the kind that blindside you at 4 p.m. on some idle Tuesday.” —Baz Luhrmann, “Everybody’s Free”

My life was turned upside down when I suffered a traumatic brain injury (TBI) during a Muay Thai sparring session in San Francisco. I immediately suspected something was wrong as I felt a strange sensation in my head, but as I had no other symptoms, I didn’t think too much of it and kept going on with my life as normal.

Two weeks later, I suddenly felt extremely dizzy and started to get painful headaches. I knew I was in big trouble when I tried to read a book but couldn’t understand what the sentences meant. Individual words were fine, but when I tried to string together a whole sentence, it just wouldn’t click. My symptoms began to spiral, and before I knew it I found myself in the emergency room.

What I thought would be a quick stint on the sidelines turned into the most difficult and prolonged ordeal of my life. I was on disability leave for nearly a year, and even today I’m still not fully recovered. It’s been a tough experience, but one that in a strange way I’m immensely grateful for. What I’ve learned from the process, which I’ll be sharing in today’s post, has been a huge unlock both as a PM and in life more broadly.

—

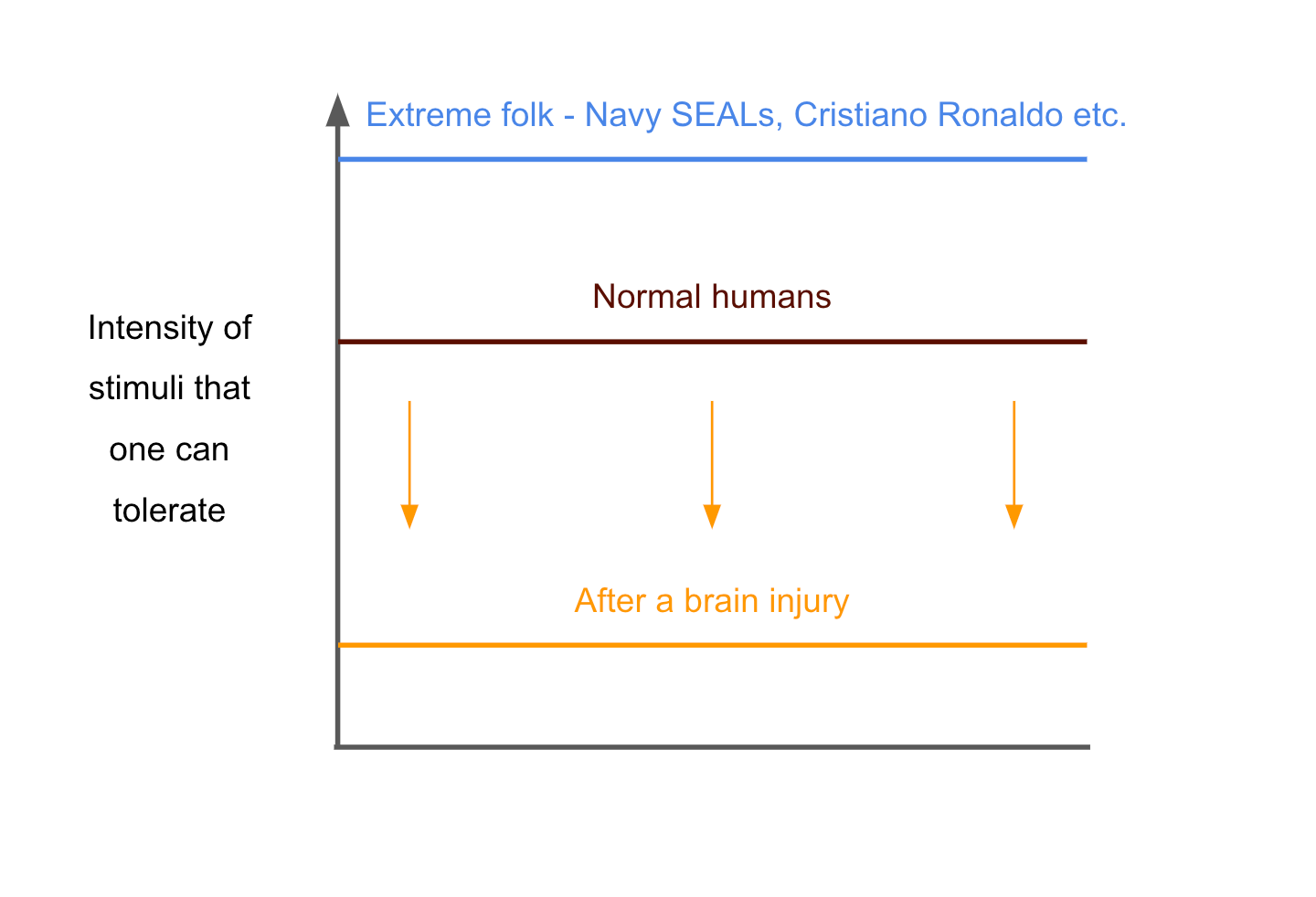

Most mild TBIs heal within weeks, but for 10% to 20% of people, including yours truly, symptoms don’t get better and persist for a much longer time. Everyone’s symptoms vary, but generally, the body’s capacity for stimuli falls to a much lower level. This makes it a lot harder to engage in daily life activities. For example, while most people would feel nauseous if they worked on their laptop for 16 hours straight, a TBI patient may feel the same way after just a few minutes of screen time.

My main physical symptoms were dizziness, nausea, headaches, noise sensitivity, fatigue, and a range of GI issues.

For several months I couldn’t read, listen to audio, or do screen time, as even a few seconds of these activities would set off my symptoms. For over half a year I could barely walk, as any movement would trigger extreme symptoms of dizziness. I was generally unable to take care of myself, and without the support of my amazing partner, I’m really not sure how I would have gotten by.

I found myself in a very dark place as I could no longer do the activities that brought me joy. I couldn’t stop worrying about whether I’d get better, and the thought of being disabled and unable to work for the rest of my life was overwhelming. I also became very withdrawn, as social contact would trigger my symptoms.

It’s been a brutal journey requiring very “active” rehab, but I’m glad to say that I’m now about 90% recovered and can yet again do most things in life. I’m back at work, and apparently I’m now also writing 5,000-word posts for Lenny’s Newsletter!

Here’s what I’ve learned during my recovery.

Lessons from the journey

Reorienting my life to compensate for my injury has left me with some invaluable knowledge across both my personal and professional life. In this post, I’m going to share a range of frameworks and actionable tips that’ll help you better manage your energy and emotions as a PM, while becoming a happier human being in general.

Before I jump into specific tactics, a quick primer on an integral part of our physiology that many of my learnings tie back to—the autonomic nervous system.

The autonomic nervous system

Have you ever felt waves of anxiety and stress before an important meeting? And what about that conversation you had with your difficult coworker that felt like pulling teeth? Did you notice your blood boiling or heart pounding as nerves or frustration set in? If so, you can thank the autonomic nervous system (ANS).

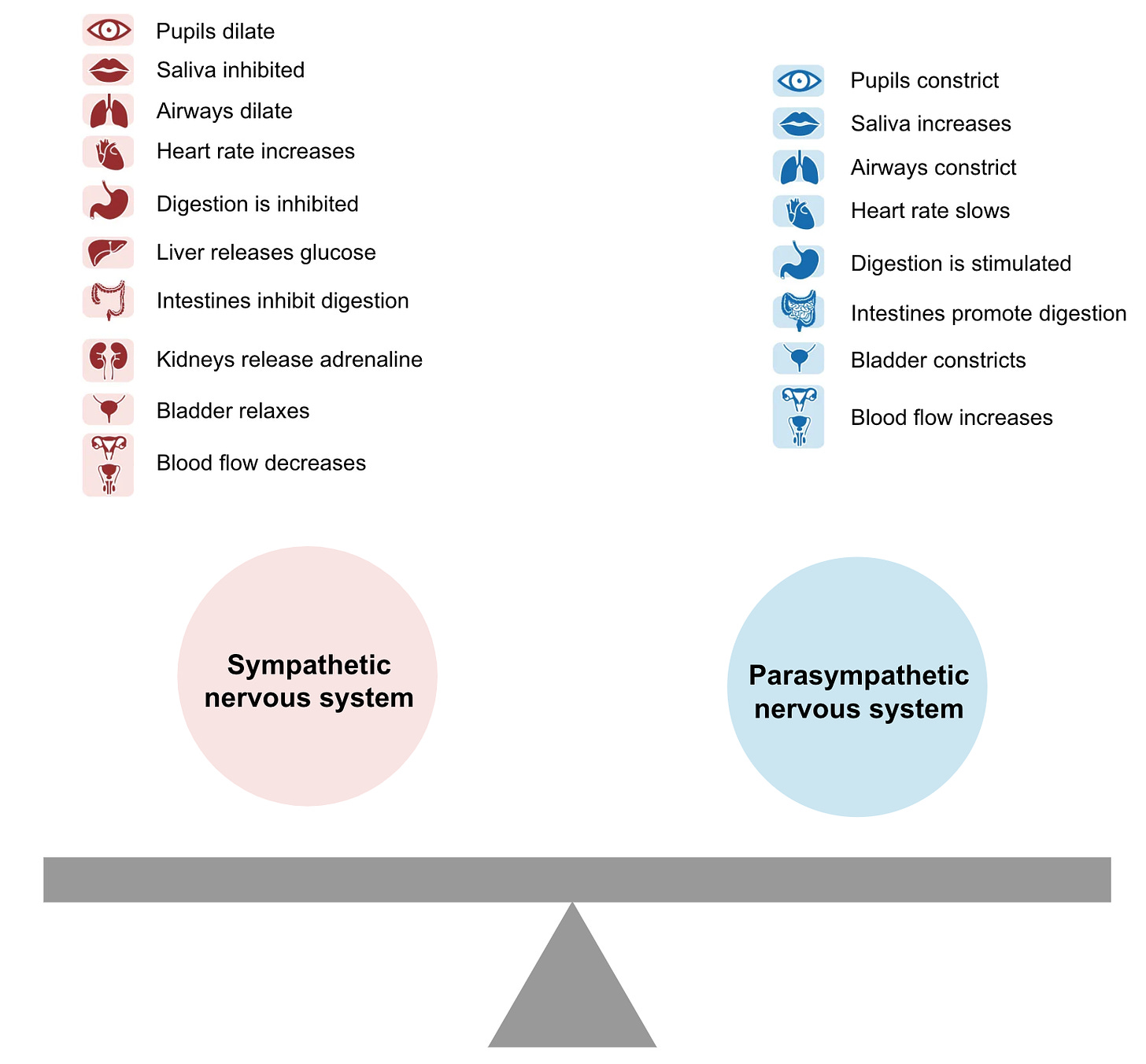

The ANS regulates a range of involuntary processes throughout our bodies. Examples include heart rate, blood flow, digestion, and our internal threat response. There are two parts to the ANS:

Sympathetic nervous system: The “fight or flight” response, which ramps up our body’s response to a perceived threat and keeps us on edge if it thinks we’re unsafe

Parasympathetic nervous system: The “rest and digest” response, which relaxes our body, conserves energy, and promotes digestion

In a healthy ANS, these systems are in a state of flux and balance each other as situations arise.

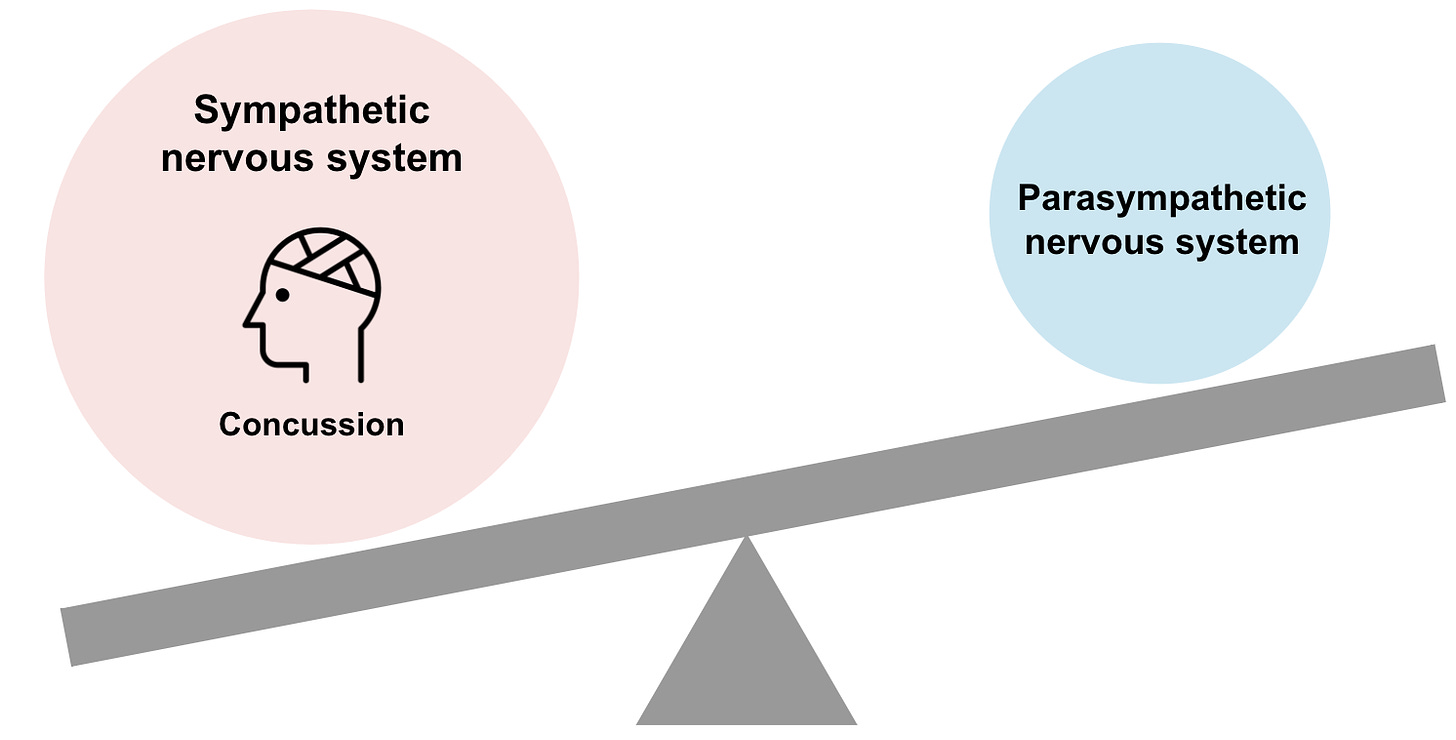

After my TBI, I developed ANS dysfunction, with my nervous system getting stuck in “sympathetic dominance.” In other words, the fight-or-flight response became my default state. This led to a range of issues, including excessive anxiety, insomnia, digestive issues, higher cortisol, and more.

Why is this relevant to you? Turns out that chronic stress also results in sympathetic dominance, where your fight-or-flight response gets stuck in overdrive. If you’re dealing with higher baseline stress levels than you’d like, this system is playing a key role.

So. . . what can you do about this? The answer lies in stimulating the parasympathetic rest-and-digest system. This response reduces baseline levels of stress and is also a useful tool to remain calm in high-stakes situations—such as a contentious product review. A decent chunk of my recovery journey and what I cover below ties back to this core, overarching principle.

Managing energy

After nine months of working up my tolerance for screen time and cognitively challenging tasks, I finally restarted my job as a growth PM at MasterClass. Side note: I’m immensely grateful to the MasterClass team for how much they went above and beyond in supporting me throughout my recovery!

Soon after returning to work, my symptoms began to get worse. Due to my reduced physical tolerance, I kept running into strong headaches and nausea, and I’d generally end the workday feeling shattered. These symptoms would often carry over to the following day, and before I knew it, I was progressively crumbling over the course of the week.

I found a few tactics to be effective at maintaining optimal energy across the course of the day, allowing me to work in a much more sustainable manner.

Structuring my calendar for energy

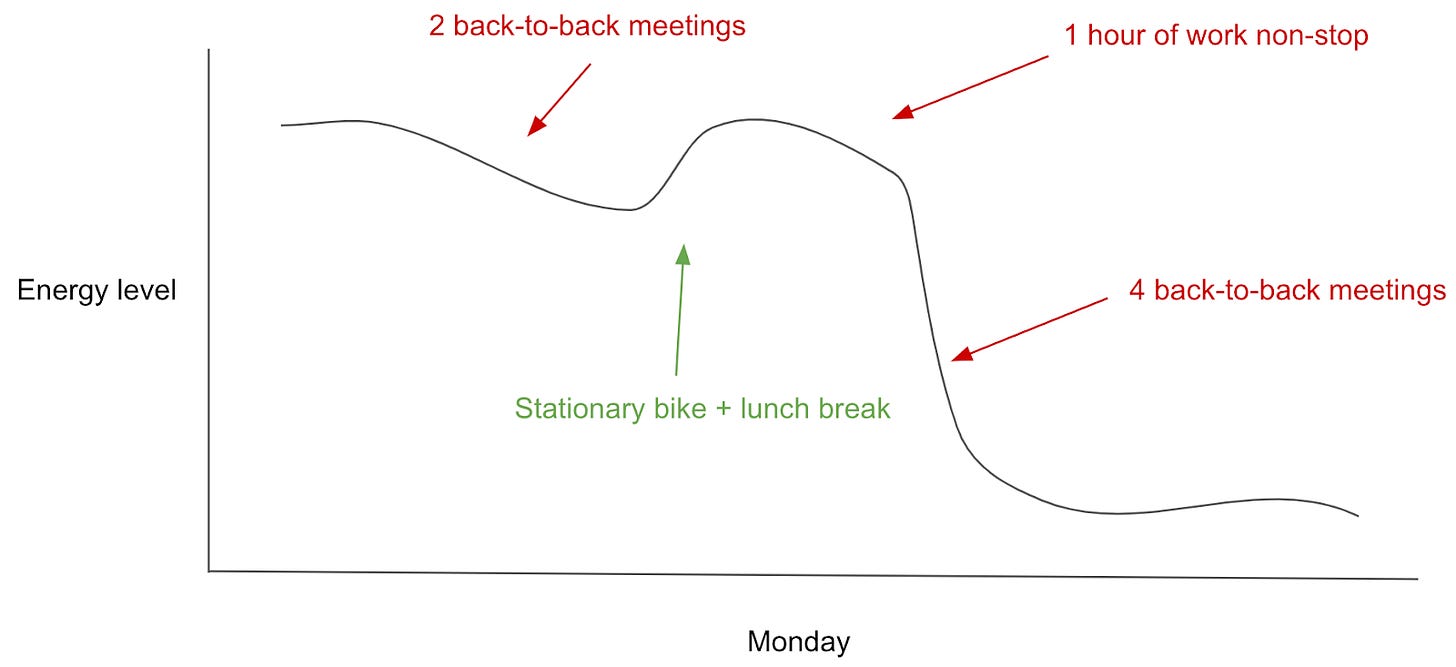

The frame of viewing my calendar as a tool for energy management was a game changer. I had to systematically think through how to manage energy troughs and maintain the right levels of energy across the week.

One simple exercise here is to map out your working energy levels. For one week, at the end of each day draw a curve of how your energy levels fluctuated over the course of that day. Make note of anything that preceded increases or decreases in energy.

At the end of the week, draw a curve of how your energy levels fluctuated over the course of the week.

The next step is to ask yourself the question, “Am I happy with what I see?” If the answer is yes, then you’re doing great! If not, you have an opportunity to restructure your week and adjust activities that are crushing your energy.

In my situation, there were a few obvious energy killers:

Meeting-heavy Mondays

Many back-to-back meetings in a row

More than 1 to 1.5 hours of continuous screen time

I was progressively losing energy throughout the week. I’d start off strong, but given the meeting-heavy nature of Monday and the start-of-week surprises that can spring up, I’d end up exhausted by the end of the day. This fatigue would carry forward and snowball over the course of the week.

I moved non-critical one-on-ones to later in the week and front-loaded some of my planned work for Monday to the weekend. Everyone has different views on weekend work, but for me, the benefits of having a lighter start to the week outweighed the inconvenience of a few hours of work on Sunday.

To help with back-to-back meetings, I started switching some Zoom meetings to phone calls and also made sure to limit myself to a maximum of three back-to-back meetings.

Also note—if you’re serious about optimizing for energy, Matt Mochary has a killer energy audit exercise that’s completely free:

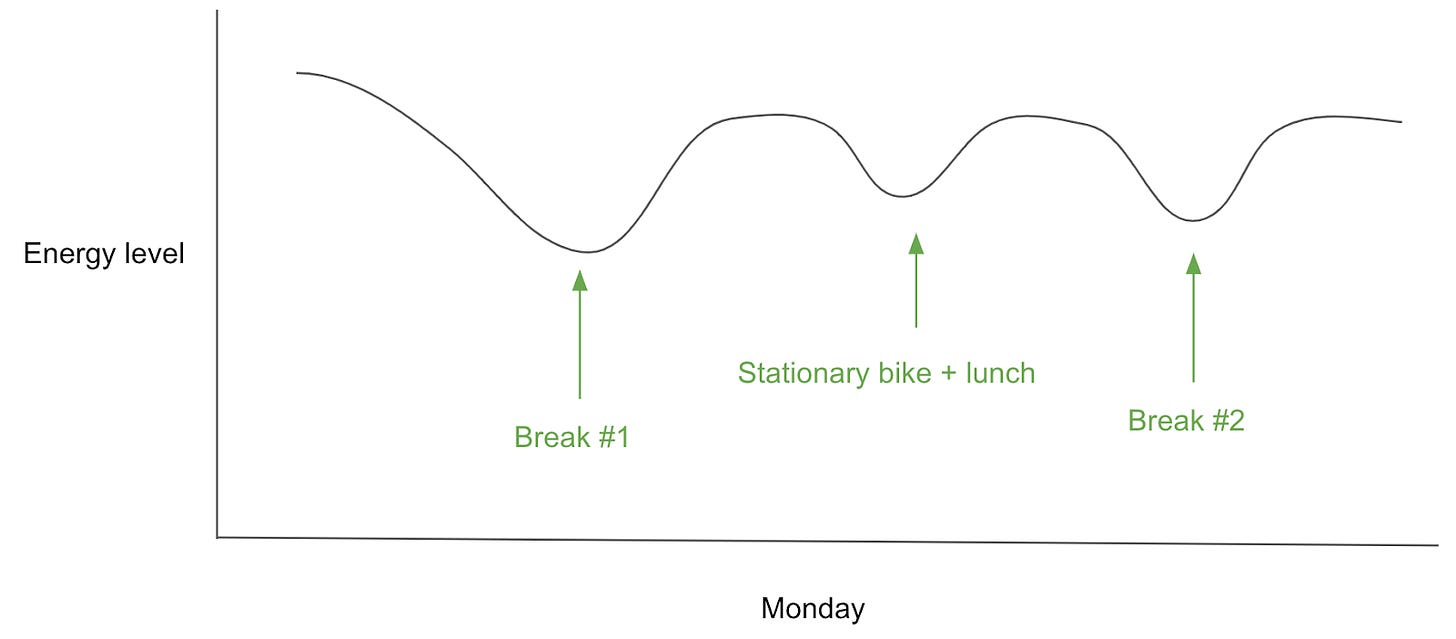

Taking breaks

One of the biggest hacks I’ve discovered is to take structured breaks throughout the workday. I put two 30-minute “DNS–Break” blocks on my calendar each day. I have one around mid-morning and the other around mid-afternoon so as to most evenly chunk up my day.

During these breaks, I disconnect from screens and focus on activities that stimulate the rest-and-digest response. For me, this has included meditation (I practice Vipassana), listening to calming music (here’s my go-to playlist), and deep breathing (two-one breathing). More on these later.

I’ve found that I often go into these breaks feeling somewhat frenetic, with anxious energy, but generally leave being much more at peace and rocking “no big deal” vibes.

For the first few months back at work, I was ultra-strict with taking breaks, as I just couldn’t function without them. Over time, I’ve relaxed this as my physical capacity has improved. I still try my best to take at least 15 minutes mid-morning and mid-afternoon to disconnect and chill out, but nowadays I’ll schedule over my blocks if I have to.

If you often feel run-down at the end of your workday, I challenge you to add structured breaks to your calendar, even if they’re only 5 or 10 minutes long. If you’re anything like me, if it’s not on your calendar, it’s not going to happen!

Ruthlessly prioritizing my time

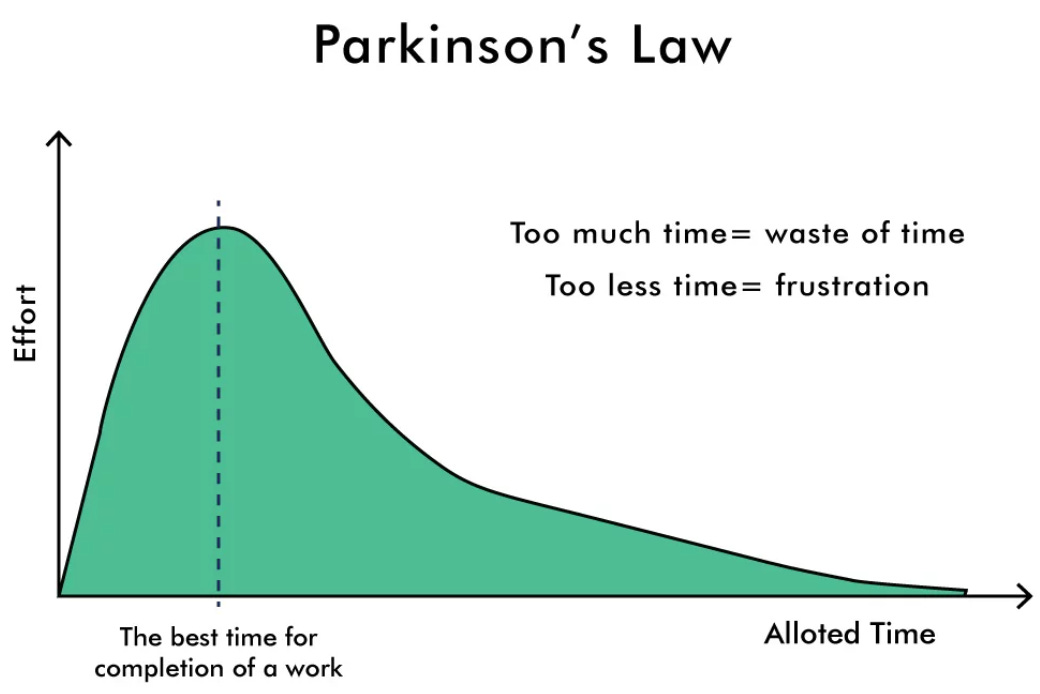

Parkinson’s law refers to the observation that work expands to fill the time that’s available for its completion. The corollary here is that work shrinks if we’re given less time in which to complete a task.

In my case, the TBI meant that in my first few months back at work, I simply didn’t have the physical tolerance that I had in the past. I needed to take breaks, I couldn’t work long hours, and I had to prioritize my health and recovery over anything else (yes, that included my OKRs!).

One of the most helpful changes I made was to set a limit of how much I would work in a day. I restricted myself to working around two hours less per day than my pre-injury baseline. I took additional breaks during the day and avoided working late into the evening.

Shorter hours raised the bar for what I considered worthy enough to invest my time in, which naturally led to better prioritization of my work. I hear this sentiment a lot from friends who’ve had kids, as they’ve similarly been forced into prioritizing more effectively to avoid completely losing their shit!

“It’s not prioritization unless it hurts.”

—Ami Vora, The Hard Parts of Growth

On a tactical level, I started applying p0/p1/p2 priorities to my daily and weekly tasks. I’ve found this helpful in reorienting myself toward higher-leverage tasks, while still making sure that I don’t drop any important balls. I limit myself to two p0 items each day, which I absolutely must get done before clocking off. I try my best to get through the p1 items on any given day but will let them slip if I have to. The p2 items are more of a stretch that I’ll only get to if my schedule permits.

Note: If a p2 task keeps getting pushed back day after day, it’s worth digging in to understand the cause. Sometimes it becomes clear to me that a task is very low-ROI and that I’m better off cutting it entirely. Other times I realize that aversion and anxiety are the real reasons why I’m delaying an important task, such as aligning with a difficult cross-functional stakeholder. In these cases, I elevate the task to a p0 to force myself to get it done.

I also started giving my talented design and engineering counterparts more ownership of work that I ordinarily covered. The key here was to work with each engineer and designer to understand their personal goals and what types of work excited them the most. For some, this included taking on more XFN comms to improve their leadership presence. For others, this involved having greater responsibility over data and analytics, or doing the work to help define our north-star vision.

I’ve found that the changes to my schedule and prioritization tactics, combined with empowering the team around me, has made me a more effective operator. It’s been a strong win-win, as I’ve given my body the space to recover while also improving our team’s performance and satisfaction levels.

Managing emotions

During the earlier stages of my recovery, I struggled to adjust to my newfound reality that life was going to be very different. The fear around whether I’d ever get better was crippling. I felt a deep frustration at my disability pressing pause on my career and life progression.

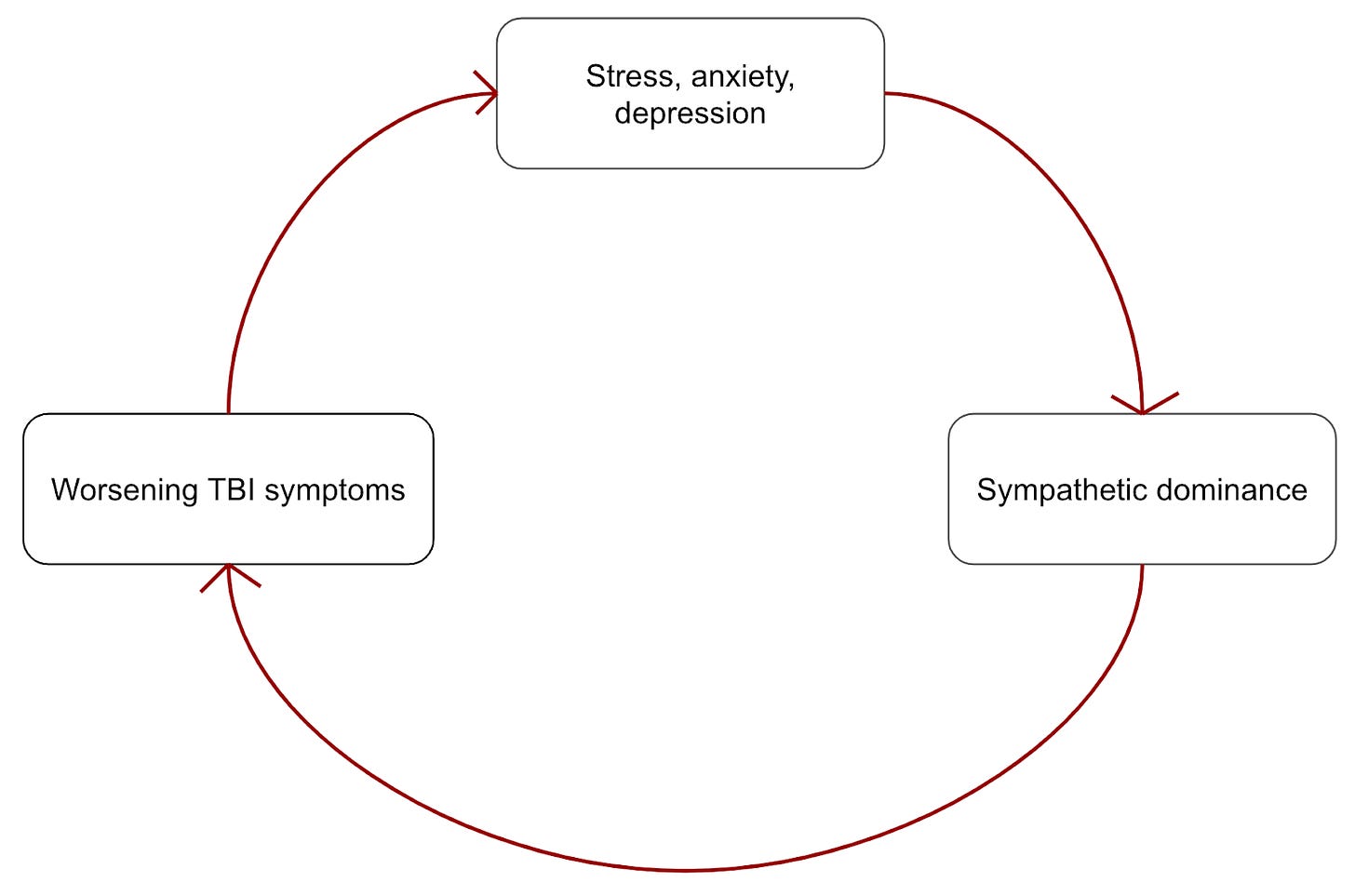

In TBI recovery, excessive anxious and depressive feelings kick off a self-reinforcing negative loop that impedes recovery. Higher stress leads to sympathetic dominance of the nervous system as the fight-or-flight response gets stuck in overdrive. Sympathetic dominance causes insomnia, which has a huge impact, given how critical sleep is for TBI recovery. Sympathetic dominance also causes digestive issues such as irritable bowel syndrome and nausea, both of which in turn lead to more anxiety and stress.

There are a few tactics that I now consider table stakes in how I manage my psychology, both in a work context and in life more broadly.

Vipassana meditation

The meditation bandwagon has hit escape velocity over the past decade. Despite how prevalent meditation has become, I find that there’s still a lot of confusion around what exactly it entails. Contrary to popular belief, meditation doesn’t require that you sit completely still for long periods of time. Nor does the inability to “clear your mind” mean that you’re doing meditation “wrong.”

Here’s one definition of meditation that I find particularly helpful:

“Awareness that arises through paying attention, on purpose, in the present moment, non-judgmentally”

—Jon Kabat-Zinn, Defining Mindfulness

Breaking this down into its inputs gives us four items:

Attention: To emotions, thoughts, and physical sensations

Intention: Being deliberate with guiding attention

Presence: Staying with what’s true in the moment

Attitude: Being curious and non-judgmental toward reality

Learning how to observe difficult thoughts and physical symptoms without judgment was a huge unlock for my recovery. In the earlier stages of my journey, overwhelming physical pain would cause me a lot of emotional strife. I’d desperately want the pain to stop, and when it didn’t I’d feel extremely frustrated about not being able to live my life.

While meditation didn’t solve all my problems, it helped me become much less reactive to all the difficulties associated with my condition. Meditation also reduced the amount of emotional pain I experienced, as I learned to struggle less against reality.

“True freedom is learning how to be at peace when you don’t get what you want.”

—Dr. Nikki Mirghafori, Spirit Rock

With Vipassana practice, I focus on an object of attention (breath in my abdomen). When my mind gets distracted, I gently investigate my thought patterns before coming back to the breath. While I choose to sit cross-legged on the floor, there’s nothing wrong with sitting in a chair, or meditating while walking or lying down. It’s important to be comfortable when you meditate, so I use a zabuton (floor mat) and zafu (sitting cushion). If physical discomfort prevents you from meditating, I highly recommend getting on these!

I aim to meditate daily for 20 minutes. Having a dedicated meditation space helps here, as does having the same scheduled time slot each day. If I’m just too busy on a certain day, I still meditate at the same time, albeit for a shorter length (even if just a few minutes). It’s important to be kind to ourselves and recognize that we’re humans, and so I do skip a day here or there and don’t see it as a huge problem. However, I’ve found that if I start to skip days too often, I become a lot less present and a lot more reactive.

Tactical deep breathing

In a work context, one of the most important tactics I’ve relied on is deep diaphragmatic breathing. There are many different types of deep breathing, and all probably work fine enough. However, two factors should be considered to best calm the nervous system:

Exhaling for longer than you inhale. Breathing in stimulates the sympathetic response, while breathing out stimulates the parasympathetic rest-and-digest response. Testing this using a heart-rate monitor will show that your heart rate rises when you breathe in and falls as you breathe out. Maintaining a 2-to-1 ratio of exhalation to inhalation ensures that deep breathing indexes your body’s systems toward rest.

Diaphragmatic “belly” breathing. Slow diaphragmatic breathing stimulates the vagus nerve, which further activates the parasympathetic nervous system. To execute this most effectively, you want to focus your breath in the region where the upper belly meets the lowest ribs.

I’ll often do this type of breathing to calm myself down before product reviews or important meetings where I expect things to get a little spicy. It’s also been very helpful after difficult meetings when I leave with anxious energy and major WTF vibes. Even just 20 to 30 seconds of this type of deep breathing can bring me closer to baseline and prevent my emotions from spiraling out. Andrew Huberman’s breathing techniques to reduce stress are also a great reference here:

Working with fears exercise

One of the most pervasive and anxiety-inducing fears I faced during the earlier stages of my recovery was the question of whether I’d ever get better. As I was still extremely limited several months after my injury, it was easy to get caught in the “I’m going to be like this forever” narrative.

Working with a therapist and learning to accept my lack of control played an important part here, as did a “working with fears” exercise that’s similar to Tim Ferriss’s thoughts on fear setting:

Write out your fear

Estimate the probability of that fear happening

Run a thought experiment of the concrete steps you’d take to survive and navigate the situation if the fear does ends up playing out

My primary fear was that I’d never be able to return to work. While my doctors were unclear on how long my recovery would take, they did believe that there was a decent chance I’d eventually recover enough to get back to a job. Nonetheless, I played out the scenario of never being able to work again. I had long-term disability coverage and was lucky enough to have a very supportive partner who could help take care of me. I reasoned that in the worst case, I could move to my native country, Australia, and at least have health-care coverage and some degree of welfare support. I knew that while not being able to work would be a very painful future, I would find a way to survive if it did end up happening.

If you want to reduce the emotional impact of fear the next time you worry about something not going your way, try working through this exercise and see where you land.

Creating a “parasympathetic space” in your house

So much of managing my emotions comes back to stimulating the rest-and-digest response. One hack that I’ve found to be very effective has been to create a dedicated space in my house with “relaxing vibes” that I use to do my deep breathing, meditation, and general chilling out.

This tip stems from the classical conditioning principle of psychology, courtesy of Pavlov’s well-known experiment. In that experiment, it was discovered that feeding dogs soon after ringing a bell would eventually lead to the dogs salivating at the sound of the bell alone, even with no food present. Why? Because they began to associate the sound of the bell with food.

The same principle applies with setting up a parasympathetic space in your house. If you have a specific place you go to where you stimulate your rest-and-digest response, over time that response will begin to fire just by going to that space.

I set up part of my room for this specific purpose with the following props:

Futon to lie down on

Cushion and mat (zafu and zabuton) for meditation

Essential-oils diffuser for stimulating smell

Speaker to play calming music

Steel tongue drum if I want to actively play music

I use this space to calm my nerves before a meeting, chill out whenever I’m feeling a bit frenetic, and during my scheduled breaks over the course of a day. Sometimes Taco (the cat) is helpful, other times he most certainly is not. . .

Managing physical health

To increase the speed of my healing and to maximize the chances of making a full recovery, I made some major lifestyle changes.

Given I’m about 90% recovered today, I no longer “have” to stick to these lifestyle changes, but I nonetheless plan to. After suffering so much from health issues, I want to maximize my probability of having a healthy life, and as such I’ve oriented toward a lifestyle that optimizes for my long-term health.

Exercise

“Exercise is the single most potent tool we have in the health-span-enhancing toolkit—and that includes nutrition, sleep, and meds.”

TBI best practices take the view that after an initial two- to three-day period of rest, daily cardio is the most important recovery activity for patients. In particular, brain injury experts recommend heart-rate-based high-intensity cardio intervals.

I worked with a physical therapist on an exercise program designed to slowly increase the maximum heart rate at which I could exercise without causing symptom onset. This involved doing one-minute-on intervals where I’d try to get my heart rate up to a target range followed by one-minute-off intervals where I’d rest and focus on deep breathing to bring my heart rate down. As walking would trigger my symptoms, the stationary bike was my poison of choice.

These short bursts of intense cardio increase brain-derived neurotrophic factor, also known as neuroplasticity. Rapidly bringing down your heart rate during the off-intervals helps stimulate the parasympathetic nervous system response.

After my injury, I was unable to lift weights, as the movement and exertion required would trigger my symptoms. The benefits of weightlifting are well documented, so over the course of a few months I worked with my physical therapist to slowly get back into light weightlifting. Being able to once again lift five times per week was a turning point that brought with it significant physical and mental health benefits.

Anti-inflammatory diet

Leading TBI experts argue that TBI recovery is held back unless diet is adequately addressed, and most agree that the best bet is the anti-inflammatory diet.

In a nutshell, the anti-inflammatory diet favors fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean protein, and healthy fats. On the other hand, processed foods, added sugar, red meats, and alcohol are discouraged.

While acute inflammation is essential to our body’s healing process, inflammation that doesn’t go away can be a big problem. Chronic inflammation, a common byproduct of our modern diet and lifestyle, is associated with heart disease, diabetes, cancer, arthritis, and bowel diseases such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

For the first six months after my injury, reducing inflammation in my brain and gut was a key goal of recovery. As a result, I was ultra-strict with adhering to the anti-inflammatory diet.

Fast-forwarding to today, the anti-inflammatory diet still makes up the core of what I eat, but I’m not going to say no to the occasional ice cream or burger. You gotta enjoy life and follow a diet that’s sustainable over the long run!

Quitting alcohol and caffeine

While the literature on whether one can drink alcohol and caffeine after a TBI is mixed, I was advised by my doctor and TBI specialists to avoid both.

In the case of alcohol, many TBI patients experience a spike in symptoms after having as little as one or two drinks. Alcohol also affects sleep, causes inflammation, and increases the chances of re-injury due to impaired coordination.

Caffeine is another sleep culprit, although the bigger issue for me was that caffeine exacerbates nervous system issues, as increased adrenaline stimulates the body’s fight-or-flight response.

I’ve long been aware that I have an addictive personality. I’d previously experimented with quitting alcohol and caffeine, so I thought “fuck it, why not” and decided to follow the doctors’ advice and completely avoid both substances.

It’s now been over a year and a half since I last drank alcohol or caffeinated beverages, and I couldn’t be happier with my decision.

Since giving up alcohol, I’ve absolutely loved getting up early on weekends and being hangover-free. I feel better and have more energy throughout the day, and also save a lot of money. Socializing while sober was tough at the start, but I’ve gotten used to it over time. Today, I’m generally very much at ease in social settings despite being fully sober. The increasing popularity of non-alcoholic beer and cocktails with 0.0% ABV makes it even easier.

Caffeine has been slightly harder. Getting back to work was a tough jolt to the system, and the fatigue I was running into definitely made me miss drinking caffeine. Having said that, my energy has improved over time, and I can now work at a high-output level without needing any caffeine. I do miss a good matcha latte, though. 😢

Other helpful frames

Beyond managing my energy and emotions, I’ve also realized how important of a role perspective plays. Being intentional with perspective-taking improves life satisfaction, while making it easier to undertake desired life changes.

Taking on something positive that you enjoy

The first few months after my accident were the toughest. I couldn’t play sports, work, listen to music, watch Netflix, travel, hang out with friends, and so on. It felt like I’d lost all the joy in my life, as I could no longer do most of the activities that I ordinarily loved.

My lesson here is that when life goes south, you need to find at least one activity that brings positivity to your life. Having just one positive thing to look forward to can flip your perspective on life, even if everything else is completely fucked.

Meditation

Initially when I couldn’t do anything else, meditation was my savior. I’d been meditating on and off for a decade and had always wanted to go much deeper into the practice. In this sense, my injury was a blessing, as I had months on end where I couldn’t do much else. It just so happened that meditation was also beneficial to my recovery.

For the longest time, I’d wanted to do a meditation retreat but couldn’t find the time to prioritize it. After my injury, I had nothing but time. A few months into my recovery, I mustered up the courage to go on my first seven-day silent Vipassana retreat at Spirit Rock, a well-known meditation center in Northern California. I had such a blast that I went on another silent retreat at Spirit Rock just two months after my first!

Because I was finally able to go deeper on meditation, the feeling of months going by where I did “nothing” no longer felt like wasted time. Instead, it began to feel like a unique opportunity to pursue a lifelong passion.

Writing

Another long-term unfulfilled desire had been to start writing online in some capacity. I’d just never found the time or the right moment to get started.

As I slowly increased my screen time tolerance, my doctor told me to take on more cognitively challenging tasks to prepare myself for eventually going back to a full-time job. After initial hesitation, I started writing about my injury and recovery on a blog. As my recovery progressed and I started to think about returning to work, I switched over to writing about recent product and experiment launches.

This slowly evolved into Time to Ship, a short-form daily digest where I recap the latest features shipped by product teams. Writing has brought me immense joy and satisfaction, and mind-blowingly, the newsletter is now read by thousands of PMs around the world!

If you’re feeling like you’re in a bit of a rut or that you’re not getting enough joy in life, I’d encourage you to think about what you can take on that you feel excited and motivated by.

Taking a wider perspective

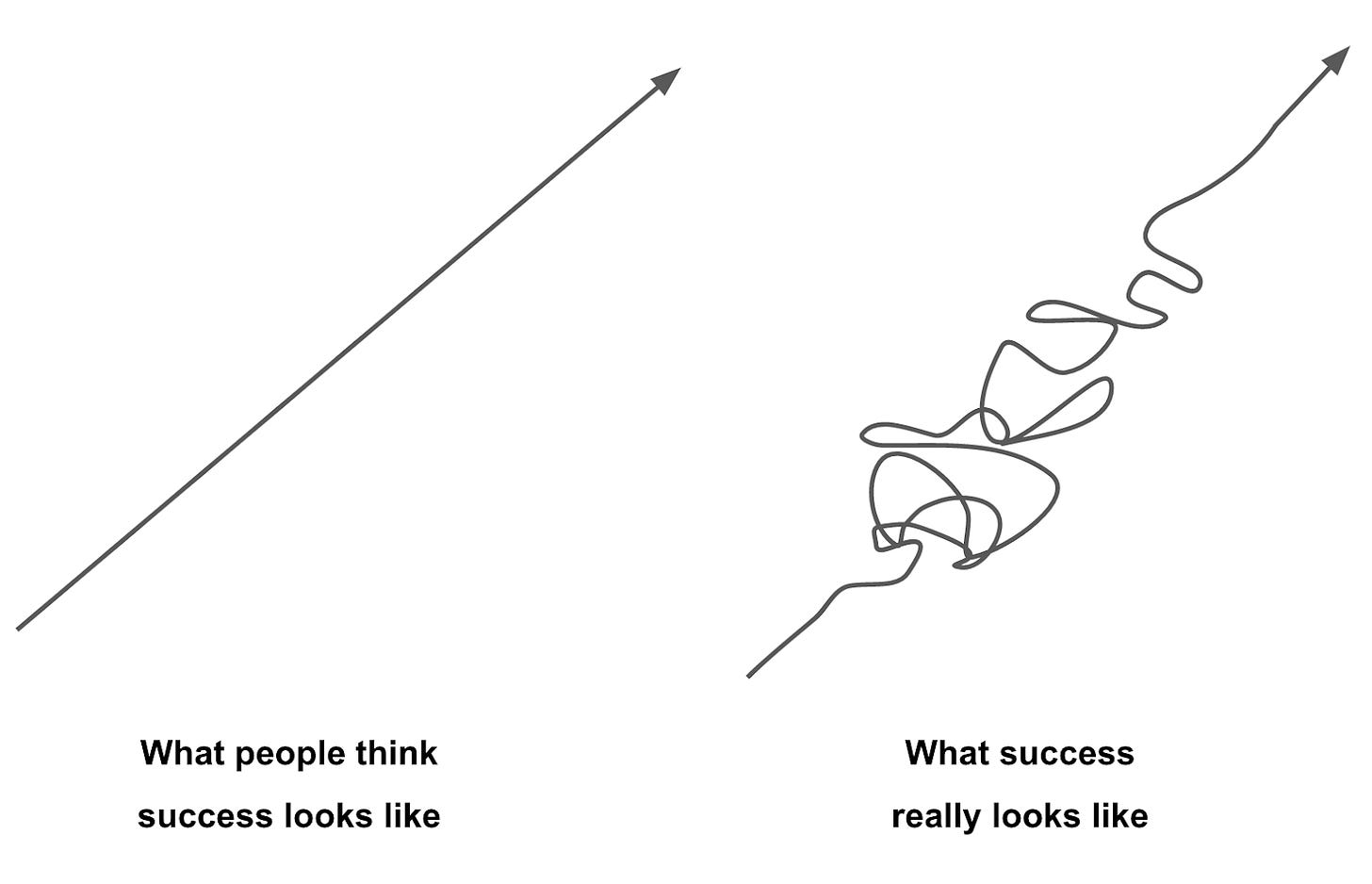

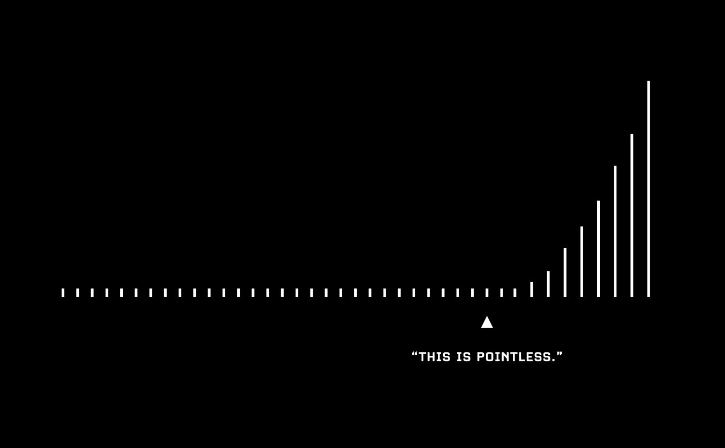

They say that success rarely looks linear, and instead more closely resembles a squiggly chaotic line that goes all over the place before eventually heading up and to the right (in the ideal world).

My recovery process was a squiggly line in every regard. So many times, just when things were starting to get better, I’d have a major setback and feel like I lost months of progress. To say this was demoralizing would be the understatement of the year.

In these moments, it was very difficult to not lose hope, as the “I’m never going to get better” narrative would take hold. During one of these setbacks, my therapist asked me an important question.

“How wide is your frame of reference?”

When suffering from strong and painful symptoms, I often defaulted to a very narrow view of my recovery. What I would miss was that even if the preceding days or weeks had not been great, if I zoomed out to take a wider frame of reference, it was clear that the overall trend line was positive.

Learning to take a wider frame was extremely helpful when the going got tough, and this principle has strong applicability in a broader life context.

Let’s say you’ve been hard at work on a project or improving some aspect of yourself. If the goal is lofty enough, you’ll inevitably run into major obstacles. You’ll feel like you’re hitting a wall and question whether you’ll ever reach your goal.

Zooming out and taking a wider frame of reference is helpful in a bi-directional way. Looking at progress over months and years instead of days and weeks may help you realize that in fact you are progressing, and that it makes sense to stay the course.

However, the converse is also true here. After zooming out and taking a multi-year view, you might realize that you’ve gotten stuck and aren’t progressing as quickly as you’d like. This can act as a wakeup call to start taking stronger actions to make a difficult change.

A new lease on life

It’s been a tough ride, to say the least, but I’m immensely grateful for my TBI journey. There was no escaping my situation, and being forced to face my challenges head-on has left me with knowledge that has significantly improved the quality of my personal and professional life.

I’m thankfully continuing to get better and better over time. Last month I went scuba diving in the Great Barrier Reef, and in December I’m flying to Nepal to do Everest Base Camp. In true growth PM fashion, I also successfully converted my girlfriend to fiancée!

All of us will experience a major decline in health at some point. That’s life, until the day we’re no longer here. However, we can maximize the probability of staying healthy over the long run by maintaining positive habits and lifestyle choices.

Working hard is undoubtedly important, but it’s also critical to do whatever you can to reduce the physical and emotional load caused by an ambitious career.

I consider myself fortunate to have experienced firsthand what it’s like to be disabled for an extended period of time, and I now have a much deeper appreciation of just how awesome life is when you have great health. Do not take it for granted.

Thank you, Amol, for sharing this story with us. For more from Amol, follow him on LinkedIn and Twitter, and check out his newsletter Time to Ship, a daily digest of the latest features shipped by your favorite product teams.

Finally, here’s a handy checklist of all of Amol’s lessons:

Have a fulfilling and productive week 🙏

If you find this newsletter valuable, share it with a friend, and consider subscribing if you haven’t already. Check out group discounts and gift options.

Sincerely,

Lenny 👋

Amol -- Congratulations on your progress! My husband had unexpected emergency brain surgery 8+ years ago. He was struggling with his short-term memory and like you, had issues with screens, reading.

I was talking to a close friend of ours at the time as how I was scared for him bc he knew what was going on but couldn't articulate things as well as normal. Like you, his mental health suffered.

Our friend said, "Maybe this is Hubs v2.0 and you have to rethink what that means."

That one comment helped reshape everything because he became much more empathetic (as did I) during his rehab.

It was horrible what he went through (had to relearn walking, talking, eating, etc as well) and we have annual brain scans.

But now we celebrate his "surgiversarry" annually as a testament to his recovery and perseverance.

Good on you for acknowledging the objective and subjective parts of your updated self!

PS - What helped my husband get over the cognitive hump he had was to listen to 15-20 minute podcasts on subjects he enjoyed. Then we discussed them. As an introvert, him going on screens at that time would have been awful.

Again, all the best!

Outstanding article! Thank you for sharing Amol!