👋 Hey, I’m Lenny, and welcome to a 🔒 subscriber-only edition 🔒 of my weekly newsletter. Each week I tackle reader questions about building product, driving growth, and accelerating your career. For more: Lenny and Friends Summit, happening October 24th | My recruiting service to hire your next product leader | Podcast | Lennybot | Swag

Jules Walter—an illustrious Newsletter Fellow and the author of one of my most beloved guest posts, How to develop product sense—is known for his ability to align difficult stakeholders on the gnarliest projects in record time. He’s developed this skill over his more than 10 years leading products and teams at YouTube, Slack, and Google Gemini, as well as mentoring hundreds of PMs through the Black Product Managers network that he co-founded. Below, Jules demystifies what might be the central skill of great product managers: influence.

Jules Walter is a product leader at Google working on Gemini. Previously he was at YouTube, where he launched Primetime Channels with more than 40 streaming packages, such as NFL Sunday Ticket. Prior to Google, Jules spent four years as a product leader at Slack on their growth and monetization teams. While there, he was a key contributor to Slack’s 10x growth. Jules is passionate about building helpful products at scale and improving inclusion and diversity in the industry. He serves on the boards of CodePath and Black Product Managers, two organizations he co-founded to support underrepresented people in tech. He lives with his wife and two kids in Berkeley, California. Follow him on LinkedIn and X.

As a product manager, or basically any leader, your ability to influence others can move your career forward or keep you stuck. And even though it’s such a critical skill for PMs, there isn’t much practical advice on how to develop it. Through years of trial, error, and mentorship, I got better at influence—so much so that a respected Google leader once told me that I “bend people to alignment.”

At Slack, I successfully navigated a significant and controversial shift in the company’s monetization strategy. Later, at Google, I negotiated across teams to overhaul YouTube’s infrastructure, design, and policies, enabling it to support high-profile TV content like NFL Sunday Ticket. My ability to influence people has impacted not just the projects I’ve landed but also my reputation and career trajectory. And as I’ve advanced in my career, influence has only become more essential.

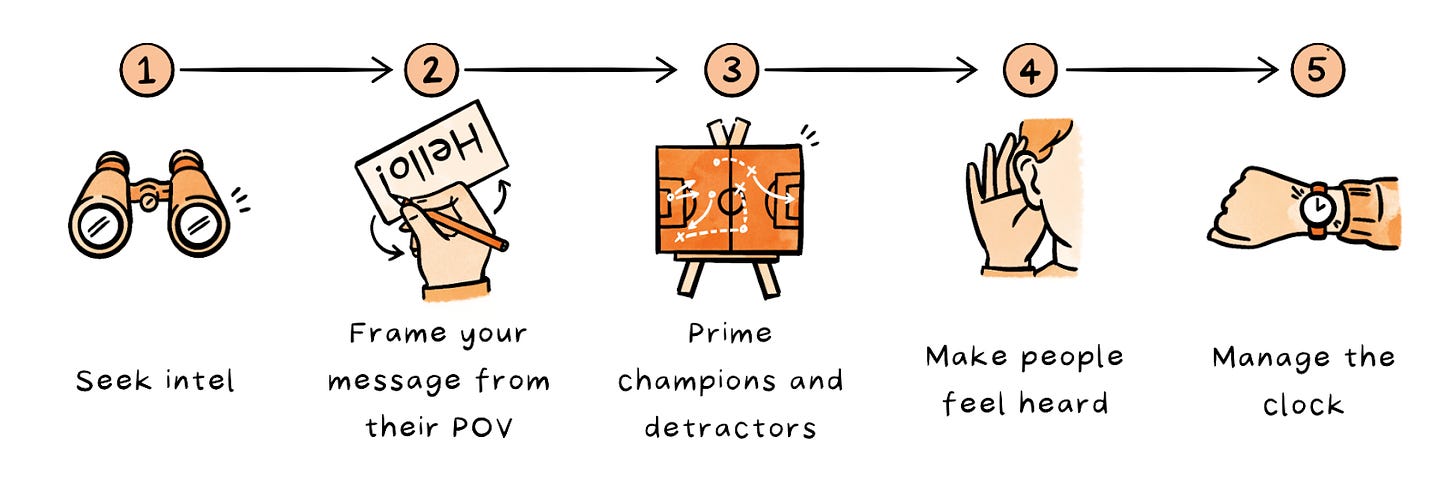

In this article, I’ll share five proven tactics I’ve used to drive alignment on complex initiatives at Slack, YouTube, and now Gemini, that you can leverage in your own work.

Tactic 1: Seek intel on how each stakeholder makes decisions

To effectively influence stakeholders, the first step is to understand how each person makes decisions––what they value (e.g. goals, incentives), who they consult, and what they’re afraid of. I usually start by setting up one-on-ones with key stakeholders (or people who know them), to understand their POV.

At YouTube, I needed the leads of a critical partner team to prioritize a feature that would otherwise delay my project by at least a quarter. I set up one-on-one meetings with the PM and engineering leads on their team. I explained to them what my project was trying to achieve, but also, more importantly, I asked questions such as:

What are the top goals and OKRs of your team? (I’ll later need to show how my project might contribute to those goals.)

What projects do you think will contribute the most to these goals? (These are the top projects I’ll be competing against.)

What’s your process for deciding what to take on each quarter? (I want to understand the steps I’ll need to go through and key deadlines I shouldn’t miss.)

Who are the key decision makers? What do they each care about? Who do they listen to? (I need to know which stakeholders to focus on, in what order, and how to approach conversations with them.)

What concerns do you anticipate them having about my project? (Getting ahead of identifying detractors and their arguments.)

How might I frame my project to increase the chances they support it? (An ask for advice from people who know the stakeholders the most.)

When having these early discussions, I first focus on establishing rapport. I convey that I’m seeking information at this point and not trying to convince them, because for people to share intel, they need to feel safe. They need to know that I’m here to listen, not argue with them, and that the info they share won’t be used against them at a later point. I start with statements like “This conversation is meant to be an informal chat. I’d like to better understand your world and get your advice as I’m looking to [explain my goals] and make things easier for everyone.”

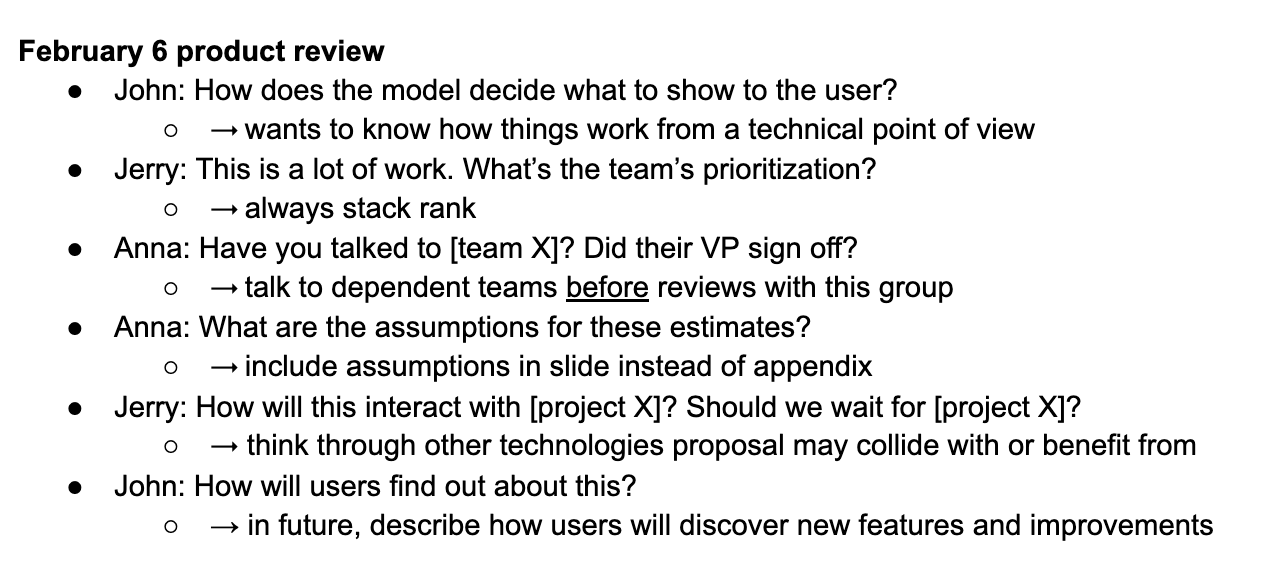

Another way I find intel on stakeholders, especially executives, is to pay attention to what they say in other meetings and forums. I keep a notes doc where I write down the questions execs ask and the feedback they give. This helps me identify their patterns and anticipate questions and reactions for future discussions when I need their support. Below is what a notes doc might look like.

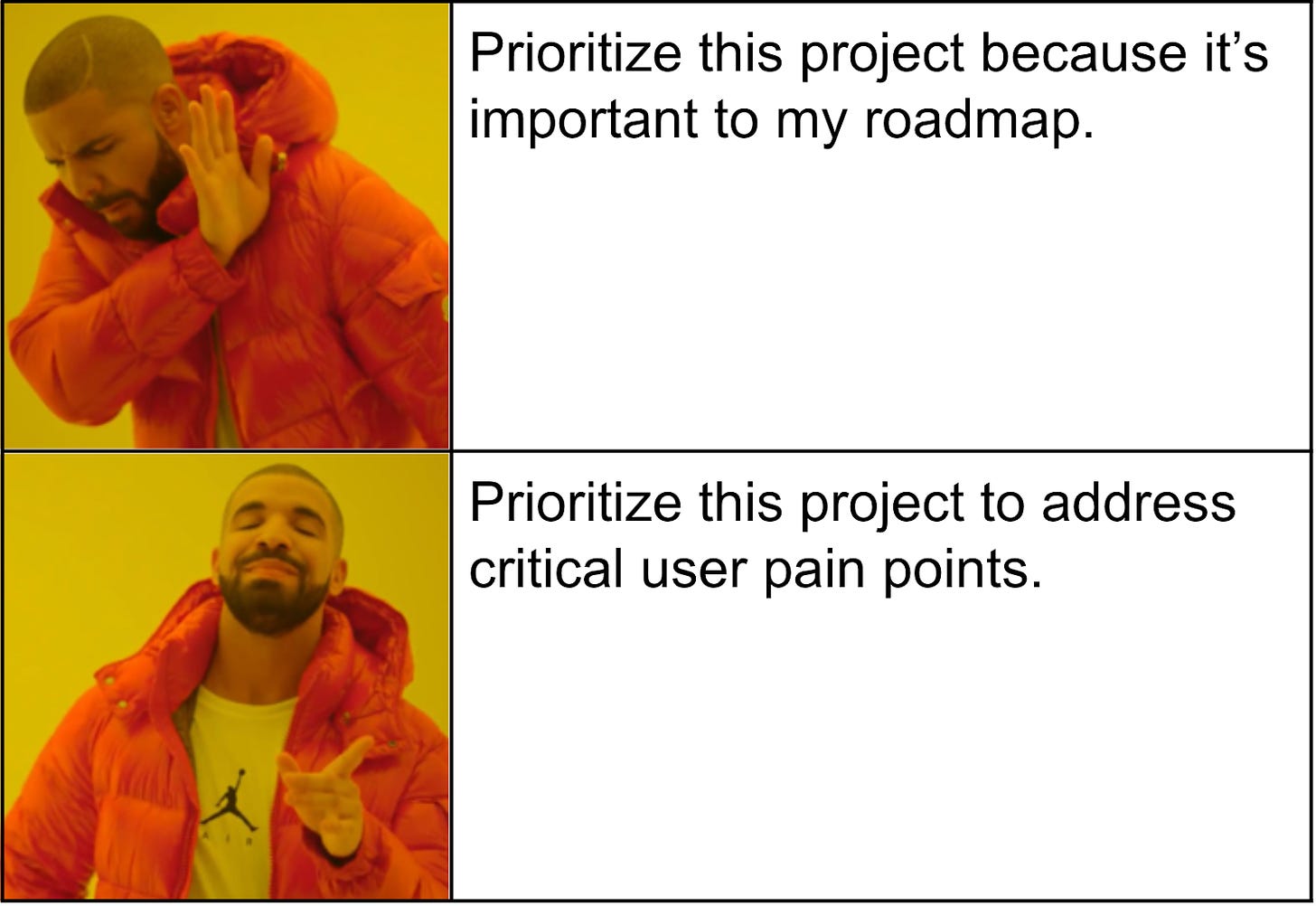

Based on the intel I gathered about the partner team at YouTube, I realized it wouldn’t be enough to emphasize how strategic my project was to the company. The partner team had a long backlog of requests from other teams that I was competing against, and they needed more confidence in my project’s expected impact on a particular metric they cared about. So I decided to walk key folks on that team through my project’s detailed forecast model to show that we would contribute meaningfully to their goals. I also recommended specific projects they could potentially deprioritize. This informed approach made it easier to influence that team, and they decided to support my team’s project, which allowed us to launch on time. This experience was a good reminder that I shouldn’t assume that others will agree that my project is a priority for the business—a tendency we PMs have—and instead be prepared to think through the right framing for my ask and provide impact assessments and other info that can help make tradeoff decisions compared with other projects.

Tactic 2: Frame your message from their POV (not yours)

“Negotiation is the art of letting the other side have your way.” —Chris Voss, author of Never Split the Difference

Once I have intel on how stakeholders make decisions, I try to reframe my proposal from their perspective instead of from mine (which is our natural tendency). It’s often more effective to speak their language and demonstrate how my proposal will help them reach their goals, not mine, because stakeholders are focused on their own problems and are more receptive to proposals that address what’s already top of mind for them.

A few years ago, when I was leading Monetization at Slack, we began to encounter diminishing returns in our product iterations, and we needed to take a bigger swing to re-ignite revenue growth. To do that, I spearheaded a controversial project to experiment with a new approach to free-to-paid conversion. The CEO, Stewart Butterfield, had strong reservations about the project. I knew from his previous statements that he didn’t want the company to be thinking about ways to extract value from users, but rather ways to create value for them.

We had scheduled a review with the CEO and a few of his VPs to discuss the proposal. Since he was intensely user-driven, I framed the entire proposal around the benefits it would have for users (the CEO’s POV) rather than emphasizing the revenue impact of the project (our team’s goal). I started the meeting by anchoring the proposal on user-centric insights that we shared in a deck:

“About 10% of purchases of Slack’s paid version happen from users in their first day on Slack.”

“Paid users find more value and retain better. Yet we make it hard for people to discover that Slack has a paid version that’s more helpful.”

“How do we help new teams experience the full version of Slack from the start?”

Once we framed the issue with this user-centric lens, the CEO was more open to our proposal and let us try a couple of experiments in this new direction. This user-centric framing also got the cross-functional team more excited and set an aspirational North Star with clear guardrails, which then enabled various teammates to contribute productively to the project. After we tested two iterations of our monetization experiment, we landed on a version that resulted in a significant increase in revenue for Slack (a 20% increase in teams paying for Slack) and we used what we learned to shift Slack’s monetization strategy into a new, more successful direction.