Kickstarting and scaling a consumer business—Step 6: SCALE: Build your growth engine

How products grow, how your product will grow, and the GTM motions of today’s biggest consumer apps

👋 Hey, I’m Lenny and welcome to a 🔒 subscriber-only edition 🔒 of my weekly newsletter. Each week I tackle reader questions about product, growth, working with humans, and anything else that’s stressing you out about work. Send me your questions and in return I’ll humbly offer actionable real-talk advice. If you know someone who would benefit from this, feel free to forward it along.

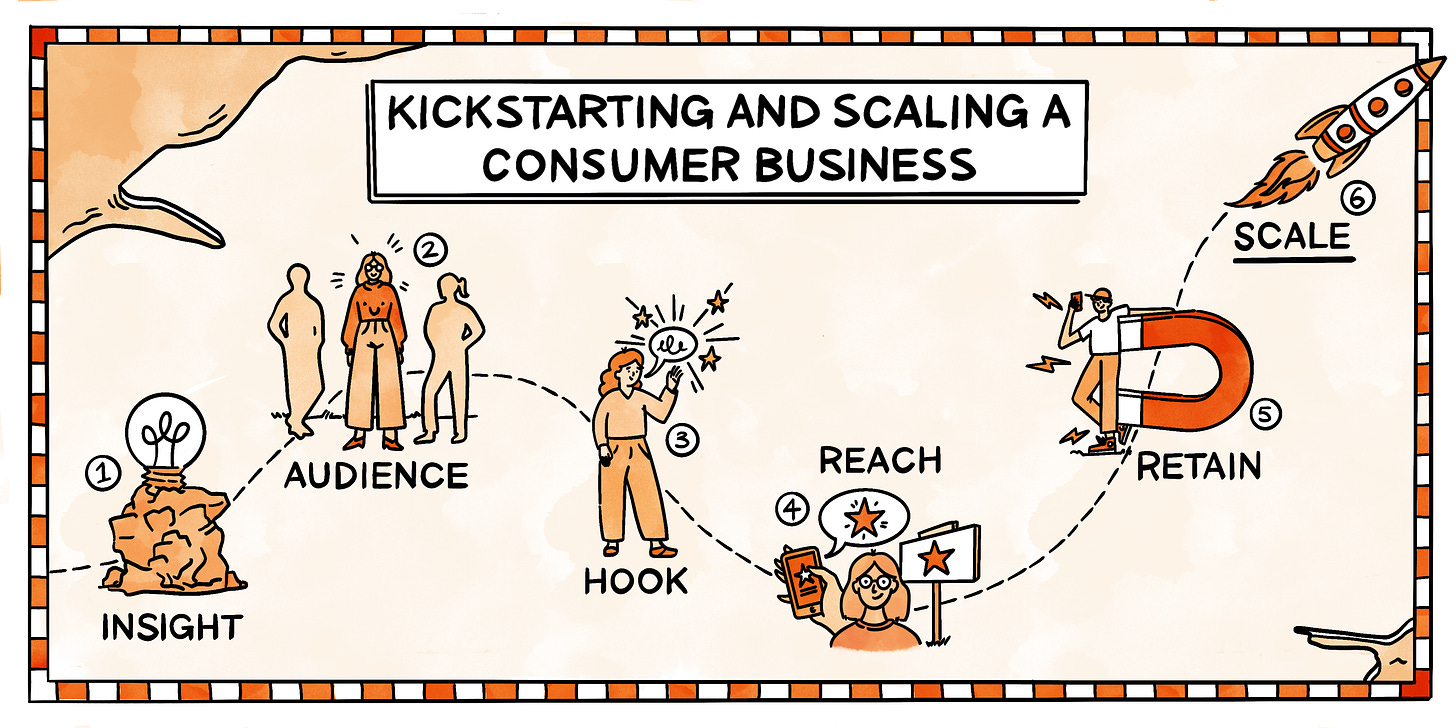

Welcome to part six (!!!) of our six-part series on kickstarting and scaling a consumer business. Here’s a recap of our journey so far:

Step 4: REACH: Find your early adopters by doing things that don’t scale

Step 6: SCALE: Build your growth engine ← This post

By this point, you have a startup idea, a product, some early users, and hopefully a glimmer of product-market fit. Even if you don’t have any of these, you should still be thinking about how your product will grow as you scale. How you grow will impact what you build, and what you build will impact how you grow.

In this post, we’ll look at:

How products grow

How your product will most likely grow

The GTM motions of today’s most successful consumer apps

Let’s get those growth engines roaring.

A big thank-you to Adam Fishman (Lyft, Patreon), Casey Winters (Grubhub), Cem Kansu (Duolingo), Gagan Biyani (Udemy), Jonathan Badeen (Tinder), Kevin Tan (Snackpass), Max Mullen (Instacart), Mike Evans (Fixer), Nickey Skarstad (Etsy), Scott Belsky (Behance), Sriram Krishnan (Calm), and Tamara Mendelsohn (Eventbrite) for contributing to this post, and Natalie for illustrations 🙏

“A startup is a company designed to grow fast. Being newly founded does not in itself make a company a startup. Nor is it necessary for a startup to work on technology, or take venture funding, or have some sort of ‘exit.’ The only essential thing is growth. Everything else we associate with startups follows from growth.” —Paul Graham

Growth used to be a mysterious dark art. Fortunately, as you’ve seen in this series, and as you’ll see below, it’s becoming much less so. There are shockingly few paths to lasting sustainable growth, and there’s a growing fountain of knowledge to help you understand each path. In this post, as we transition from doing things that don’t scale to scaling the things that you’re doing, we’ll explore how products grow, how your product is likely to grow, and how today’s biggest consumer businesses kickstarted and scaled growth. Let’s get into it.

How products grow

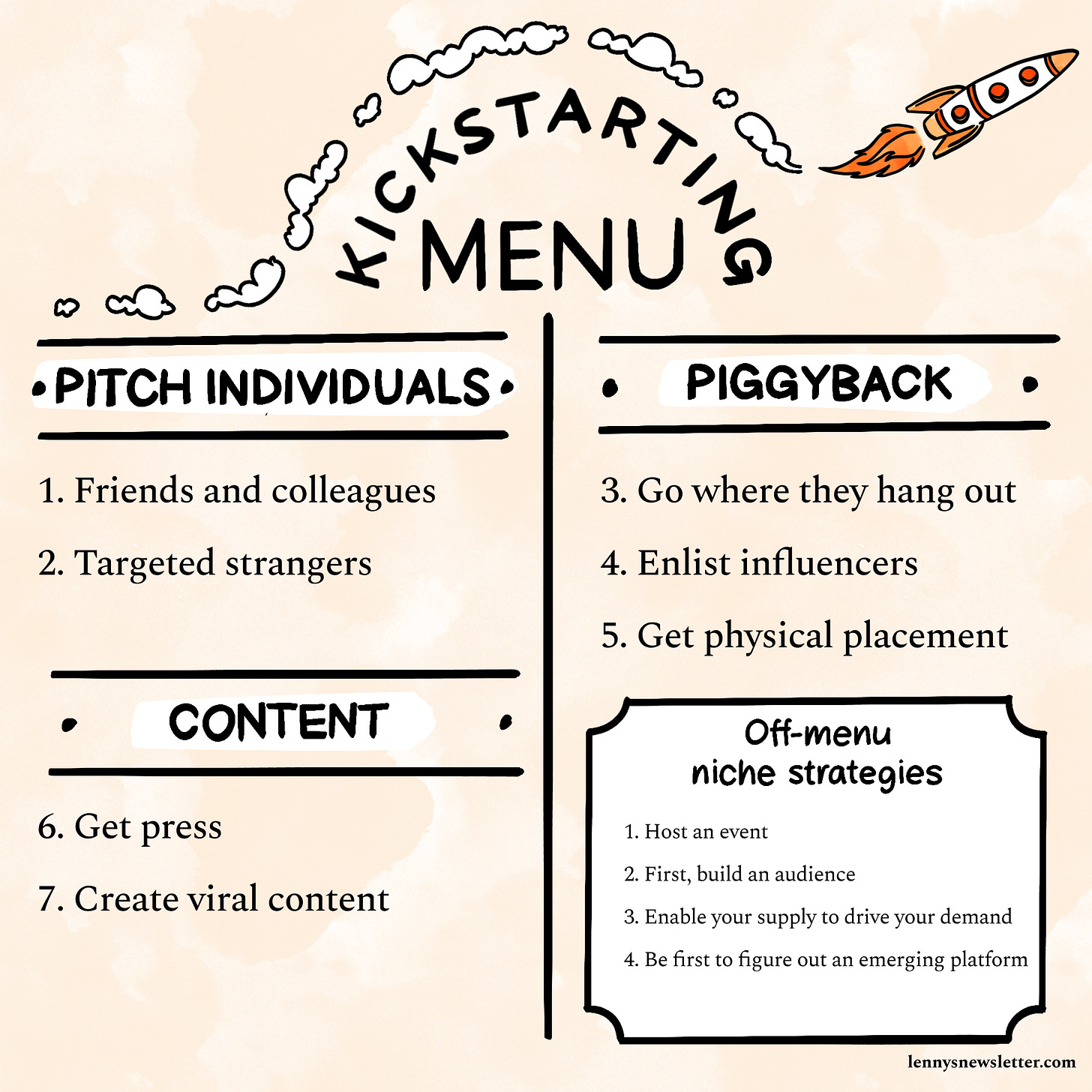

When you’re just starting out, as we saw in step four of our series, there are only seven reliable ways to kickstart your growth (i.e. get your first 1,000 users):

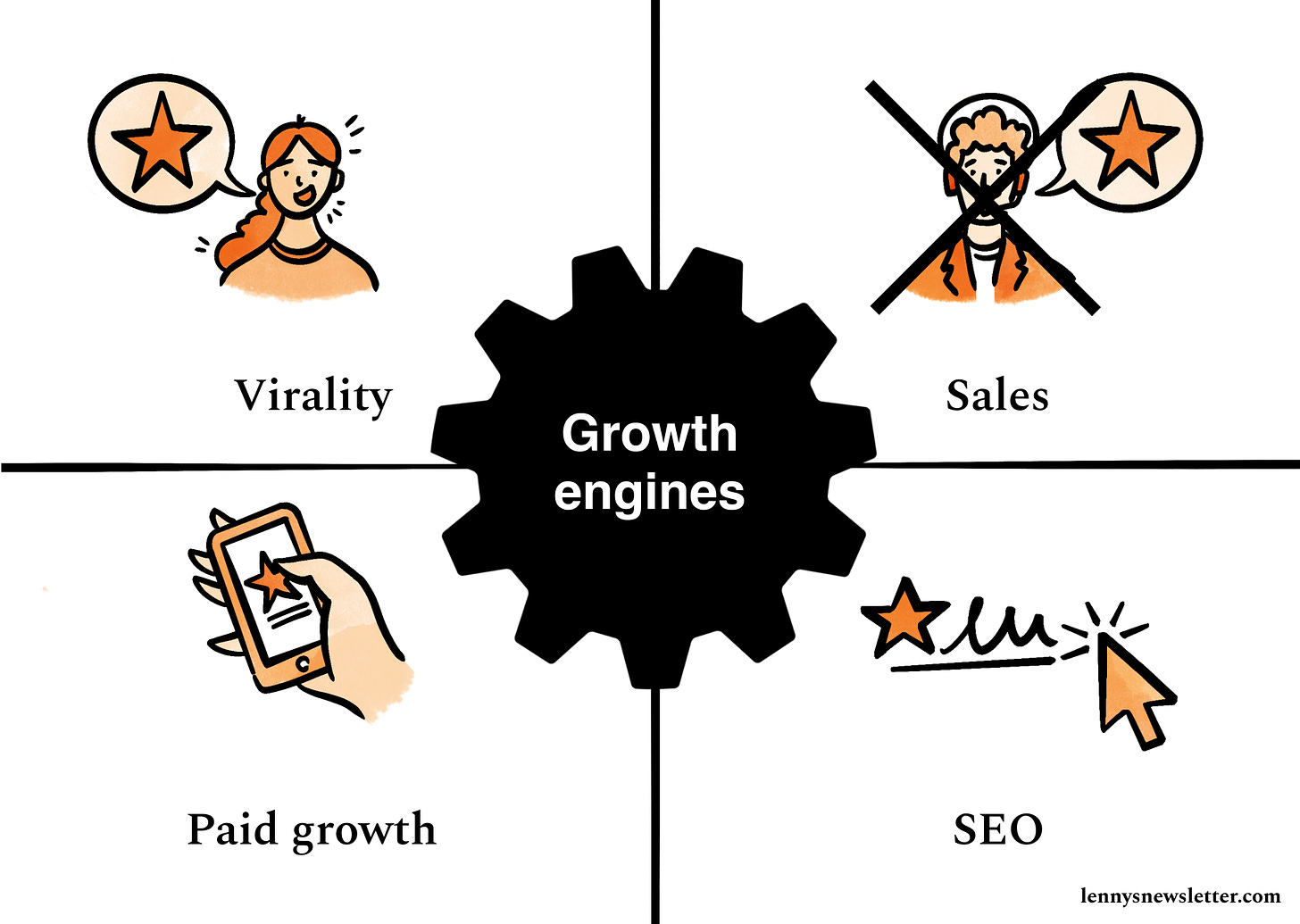

To scale your growth, your options are even more limited. There are only four sources of self-sustaining long-term growth, aka growth engines:

For consumer startups, it’s actually even simpler. There are only three feasible growth engines (since relying on sales is rarely economical):

Why so few ways to grow? Think about it. How many ways do you find out about most new products? Either you see an advertisement (i.e. paid growth), you find it while searching online (i.e. SEO), someone reaches out and pitches you on it (i.e. sales), or a friend tells you about it and/or you see it shared on social media (i.e. virality).

Even more interestingly, the majority of startups grow primarily through just one of these engines. For example, nearly 100% of Tinder’s growth came through word of mouth (WOM), Calm’s through paid growth, and Thumbtack’s through SEO. This is true for nearly every startup out there, especially at first.

A common pitfall of early-stage startups is trying to invest in too many engines at once and not nail any. At scale, in order to win a market, you have to become world-class at your primary growth engine. To quote Dan Hockenmaier and myself from a post on this topic:

“Once you get to even moderate scale, each of these engines becomes highly competitive.

In the case of paid marketing and SEO, you are competing for a customer’s attention. Paid marketing becomes a business-model competition (who can turn this customer attention into enough value that they can bid more than anyone else for that attention), and SEO becomes a ranking-algorithm competition (who can capitalize on their content in such a way that ‘deciders’ like Google want to continue to send traffic their way).”

Over time, most companies layer on an additional engine (usually paid growth, sometimes SEO) in order to continue to grow while their initial growth engine plateaus (learn about S-curves and adding layers to your cake). But timing those investments correctly is critical, and that initial engine normally continues to drive the majority of your growth.

Note, even though there are a limited set of strategies, there are infinite ways to be creative about how you execute each of them, e.g. Netflix infiltrating DVD forums, Hipcamp setting up tables outside REIs, Airbnb selling cereal.

Your job as a founder looking to grow your product is to (1) creatively execute two to three kickstarting tactics and (2) become world-class at one primary growth engine. That’s essentially your high-level GTM strategy. Here’s a link to the worksheet we’ve been using throughout this series to help you plan your GTM.

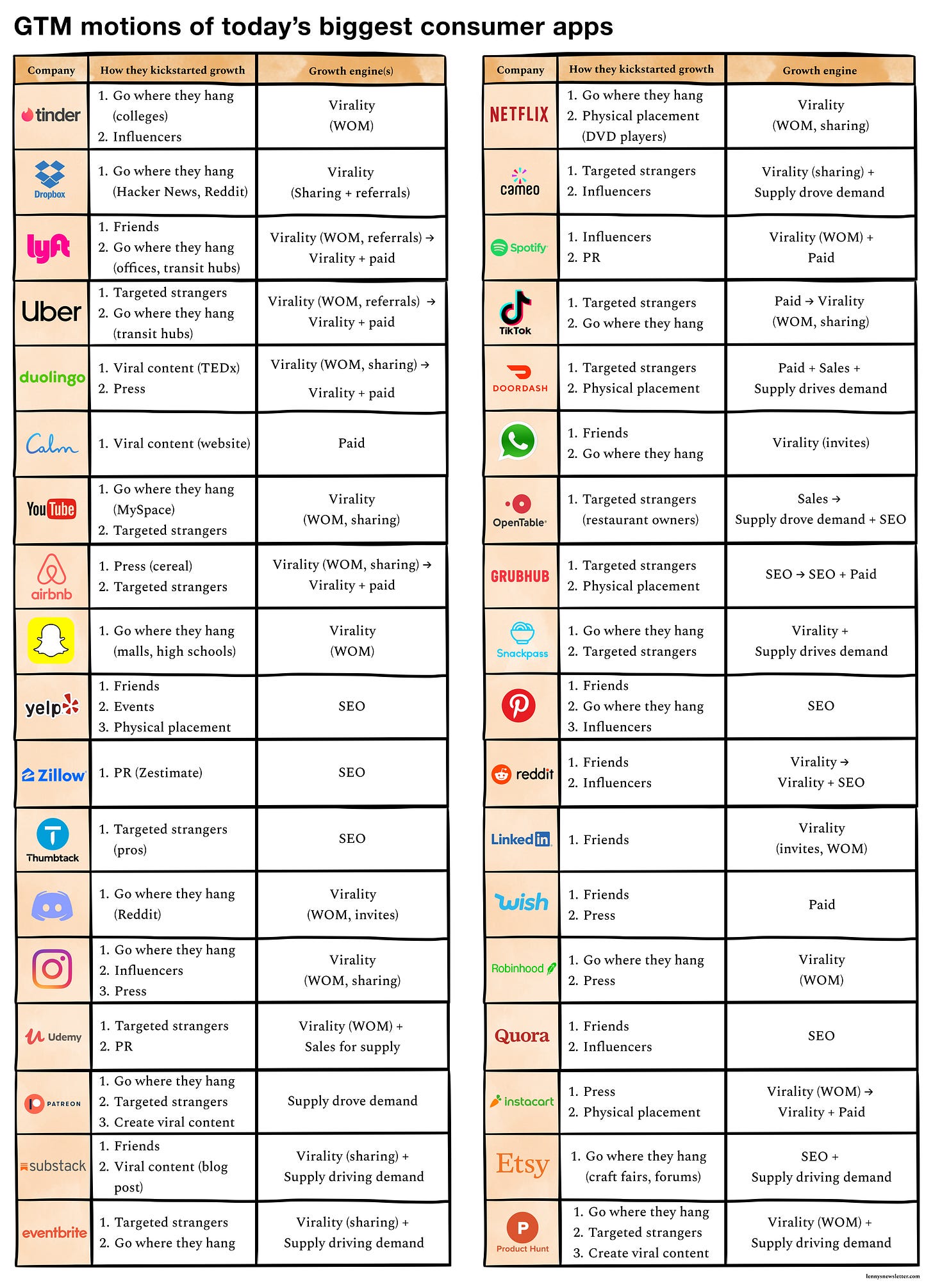

GTM motions of today’s biggest consumer apps

To bring it all together, here’s an overview of how today’s biggest consumer businesses kickstart their growth, and their primary growth engine.

A few stories I’ve gathered from founders and early employees describing their primary growth engines:

1. Virality (which can be driven by word of mouth, sharing content, sending invites to your friends, or a referral program)

Airbnb (WOM, referrals):

“If you look at the composition of growth of Airbnb, WOM was by far the biggest driver early on. Way over 50% on the guest side and way over 70% on the host side.”

—Gustaf Alströmer, first head of growth

Instacart (WOM, referrals):

“What showed up in our data was that we had strong word-of-mouth growth (people would report hearing about us from a friend, or they would use our referral program with their first order).”

—Max Mullen, co-founder

Udemy (WOM):

“Over 90% of our courses were created organically—which means word spread quickly. People started to realize the value of Udemy and clearly wanted to come.”

—Gagan Biyani, co-founder

Behance (WOM, sharing content):

“We had a year of deep focus on viral spread—syncing Twitter, FB, and other social media accounts to automate sharing every time a member posted a new project, new reasons to share projects even when they weren’t yours, and making sure our SEO game was solid.”

—Scott Belsky, co-founder

Instagram (WOM, sharing content):

“When Instagram launched to the public on October 6, 2010, it immediately went viral. It reached number one in camera applications in the Apple app store.

Within the first day, 25,000 people were using Instagram. Within the first week, it was 100,000, and [co-founder Kevin] Systrom had the surreal experience of seeing a stranger scrolling through the app on a San Francisco bus. He and [co-founder Mike] Krieger started an Excel spreadsheet that would update live with each user added.”

ーNo Filter: The Inside Story of Instagram, by Sarah Frier

LinkedIn (inviting friends):

“The site launched on 5/5/03, and after a week we had something like 12.5K registered users ... After about four months we hit 50K users and then 500K a little less than one year after launch. Keep in mind, in the early days there were no public profiles or other ways to view the site as a non-registered user.

LinkedIn deployed an Outlook contact uploader (very painful to build/support) to allow viral spread among professionals. Even today, nobody else has invested energy in this direction despite the 5-10x distribution per inviter you get from Outlook vs. Webmail.”

—Keith Rabois and Lee Hower, members of founding team, via Quora

Pinduoduo (inviting friends):

“Pinduoduo’s model was simple: buy everyday items and receive discounts of up to 90% by completing in-app actions or inviting friends to buy them as well. Prices were set by suppliers, and a user’s very first purchase was almost always subsidized at a discount by PDD. Subsequent purchases could be made at the full price or discounted with a team or through in-app rewards. Users could join existing teams in the app, but prices were even lower if users started their own team. Early products were so cheap that there was very low friction to buy. The K-factor, or the average people a new user invites, was never less than 1. Any money spent to acquire one customer was ultimately acquiring multiple customers.”

2. SEO

Thumbtack:

“SEO was a big bet because it takes a long time to see results. Often you start investing in it, and the first results you see are six months in and they’re not very encouraging. You only start to see results that impact the business after 12, 18, 24 months. So we chose deliberately to put the entirety of our engineering, product, design, marketing, and operations resources—which were maybe 12 people at the time—against success in this one channel. It was a company betting decision.

For the first three months, almost nothing. And then a trickle of traffic. At six months, there still wasn’t much traffic, but there was at least enough to start analyzing. At 18 months, it became a meaningful share of consumer traffic to the site. At 36 months, it was the primary form of customer acquisition.”

Yelp:

“We had surprise success with organic search traffic. Mostly we’d ensure the site was SEO-friendly, but that was relatively minor. Mostly traffic came because we actually had quality review content and a decent page for each business.”

—Russel Simmons, co-founder

Etsy:

“The company was spending ‘next to nothing’ on customer acquisition. This trend remained fairly consistent as the company continued to grow, as revealed in their recent S-1. Since 2011, organic channels have represented 87% to 91% of Etsy’s traffic, while paid ads have been responsible for between just 2% to 7% of traffic.”

Zillow:

“SEO was and continues to be an important channel for us. We took advantage of our PR and content groups to drive traffic and links to our site and created the most comprehensive database of homes, with deep details of every home in the country (not just the ones for sale). We continue to work on providing the most unique and valuable data on every home (with things like 360-degree tours of homes).”

—Nate Moch, early growth leader

Grubhub:

“The most obvious things were SEO (and some SEM). In particular on the SEO side, we adamantly refused to build things that were meant primarily for search-engine indexing. Instead I focused on the idea that the SEO landing pages should be built with HCI principles and conversion in mind. It turns out that this kind of unique content/highly converting landing page concept also indexes very well, so that worked great. To boost this value, I added the menus for all restaurants in our markets and sorted our paying customers (with their online ordering feature) to the top of the list.”

—Mike Evans, co-founder

3. Paid

Booking.com:

“The founding company behind Booking.com actually started off as a meta-search business, and SEO was a growth driver early on. But eventually, growth started to level off because we were doing some gray-hat stuff and Google started to penalize us.

So we began exploring new ways to grow. At the time, Google was taking off like a rocket ship, and the users had so much purchase intent while searching. We thought, if we could get good at Google, we’d do really well. We thought—what if we try AdWords?

We found a company that had a massive list of points-of-interest around the world, about 6 million of them. We realized that if we could do this at scale, we could create 6 million pages to point Google ads to. […]

It was actually only two guys for a while—one banker (Peter) and one coder. I always believed that the secret to our success was that we were not heavily automated for most of our early spend. Peter (the banker) was extremely competitive. He would scream and shout when he was losing his #1 position. He had a simple success criteria: win the auction for all of the important words, and make money on it.

This small team continued to run the program even past $100m in spend. We started paid search in 2004, and in 2008 it was the biggest source of growth.”

—Arthur Kosten, early CMO, via First Round Review

Uber:

“The end state for Uber was around 50% paid growth and 50% virality (15% referrals, 35% WOM). Early days, the mix was closer to 30% referrals, 50%-60% WOM, and the rest was PR and other random things.”

—Andrew Chen, head of driver growth

Two bonus growth engines just for marketplaces and platforms: Sales, and Supply driving demand

Sales

As I noted above, sales is rarely an effective growth engine for B2C startups—with the exception of marketplaces and platforms, where the supply is incredibly valuable. In those cases, sales is both an important kickstarting tactic and an important part of the overall growth strategy.

Grubhub:

“Supply growth was all sales—door to door, walking into restaurants during their downtime, talking to owners. It was very sales-driven. What we did was take every excuse they had for not using Grubhub and removed it as an obstacle. Fast-forward to a couple of years later—you only pay when you receive orders, there are no hidden fees, you can cancel anytime. We got to a place where there was zero downside to sign up and to give it a try.”

—Casey Winters, first head of growth

Udemy:

“We ended up building a team called ‘content acquisition’ at Udemy that focused on direct outreach. This team is a lot like any other growth team—except that it was much more business-heavy. This team consisted of some virtual assistants (VAs) and some full-time employees to help manage the process and deal one-on-one with high-profile instructors. Here’s the workflow (say we are trying to get courses in Python programming):

VA 1 searches for the leading expert(s) in Python programming. VA 1 obtains their email addresses and sends them an email on behalf of a Udemy team member (aka from gagan@udemy.com).

Some percentage of instructors reply to the email.

Udemy team member gets on the phone/Skype/email and helps the instructor understand the benefits, answer questions, etc.

Instructor, sold on how awesome Udemy is, puts up their course over the next 2 weeks to 3 months.

This created an engine of course acquisition that we still use today.”

—Gagan Biyani, co-founder

OpenTable:

“On the restaurant side, unfortunately, there were no easy levers in the early days. It was hire a direct sales force on the street. People on the street knocking on doors, carrying the software. Demo’ing it and showing them how it worked.”

—Mike Xenakis, early growth leader

Etsy:

“The main thing that I believe really worked was recruiting sellers in person at craft fairs and elsewhere. This was a small activity in terms of human effort, but it scaled beyond that since the sellers marketed themselves.”

—Dan McKinley, early employee

Caviar:

“For us, for supply growth, it’s direct sales/field sales—no question!”

—Gokul Rajaram, head of Caviar

Supply driving demand

You’ll notice in the table above there’s an additional growth engine, “Supply drives demand,” that again exists only for marketplaces and platform startups. How this works is within a marketplace, your supply (e.g. DoorDash restaurants, Substack writers, Eventbrite event organizers) often drive their customers/audience to your site because it benefits them (e.g. restaurants tell customers to order from DoorDash, writers drive people to Substack to subscribe, event organizers send everyone their Eventbrite ticketing page). Although technically this is a growth engine, and an incredibly powerful one, it won’t be the source of your growth because you still need to grow the supply in the first place (usually through sales), and there isn’t a ton you can do to accelerate this engine. But when you do have this engine in place, lean into it big-time because it creates an incredible unfair advantage.

A few examples of this engine in action:

DoorDash:

“Restaurants did a lot of the marketing for us. They would actually print placards and stickers and put them up in the restaurant, without our help and often without us knowing. Stickers on the windows worked extremely well. Restaurant owners are enterprising entrepreneurs and are super-creative at driving demand.”

—Micah Moreau, VP and GM

Etsy:

“Sellers were doing their own grassroots marketing, and that became a big growth driver. Etsy pushed sellers to promote their shops to their communities in order to drive the growth of their shops, which in turn drove the growth of the marketplace overall.”

—Nickey Skarstad and Dan McKinley, early employees

Eventbrite:

“Due to the nature of organizing events, most event organizers had some built-in demand that they brought with them.”

—Tamara Mendelsohn, CMO

Snackpass:

“For us these days, it’s 50% restaurant-driven users and 50% word of mouth from users.”

—Kevin Tan, Snackpass

Learn more about kickstarting and scaling your marketplace here.

How your product will likely grow

I suspect a question you’ve had on your mind this whole time is which of the three growth engines is likely right for you. You’re probably also wondering, “Ooo, how do I grow through virality? That sounds great!” Unfortunately, that’s not how it works. Your product needs to be a fit with the growth engine, and it’ll only work out if it’s a natural fit.

Below is a handy guide that’ll tell you which growth engine is likely the best fit. Though it may not be what you want, you’re lucky if you can get even one to work at meaningful scale. What you’re looking for is an unfair advantage that allows you to become world-class at that growth engine.

You’ll likely grow primarily through SEO if:

Your users produce lots of public content (e.g. Glassdoor, Quora, Reddit, Pinterest)

You have proprietary data that you can use to generate thousands of pages (e.g. Yelp, Grubhub, Thumbtack, Tripadvisor)

Your competitors are having success with SEO—check Similarweb