How to Kickstart and Scale a Marketplace Business – Part 3: Cracking the Chicken-and-Egg Problem 🐣 - Growing Initial Supply

Rare insights from 17 of today's biggest marketplaces, including Airbnb, DoorDash, Thumbtack, Etsy, Uber and many more

“Supply growth was all sales - door to door, walking into restaurants during their downtime, talking to owners. It was very sales driven. What we did was take every excuse they had for not using GrubHub, and removed it as an obstacle. Fast forward to a couple of years later — you only pay when you receive orders, there are no hidden fees, you can cancel any time. We got to a place where there was zero downside to sign up and to give it a try.”

— Casey Winters (ex-growth at GrubHub, CPO Eventbrite)

Welcome to the third post of our limited series on marketplace growth, where I share learnings and insights from founders and early employees at today’s most successful marketplace businesses. I’ll be releasing four more parts over the next two weeks, and then I’ll return to my regular cadence of once-a-week. 🤙

I continue to be blown away by the response to this project. Thank you so much to everyone who has sent me kind words, helpful feedback, or shared these posts with others. I started this research out of a personal desire to learn more about other marketplace businesses, but seeing how valuable this has become to so many makes me feel all warm and fuzzy inside.

What I said in the last post continues to be true — it only gets better from here. If you’re new to this series, don’t miss the earlier posts covering Phase 1: Cracking the chicken-and-egg problem:

Part 2: Decide which side of the marketplace to concentrate on 🧐

Part 3: Drive initial supply 🐥 (this post)

Step 3: Drive initial supply 🐥

As we saw in the last post, the vast majority of marketplaces start off supply-constrained. Interestingly, most marketplaces continue to stay supply constrained throughout most of their history (which we’ll spend more time on later). Why are most marketplaces supply constrained? Li Jin (partner at a16z) said it well, “the best consumer marketplaces end up supply-constrained because they tap into an incredible amount of demand. The product/market fit is so strong that this demand puts pressure on supply.”

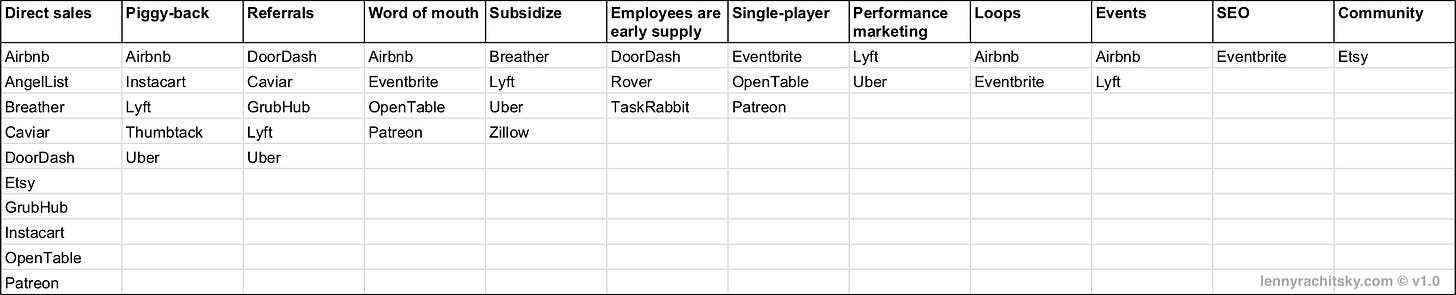

With supply being so essential, how did today’s biggest marketplace companies grow their initial supply? Below we’ll dive into each and every lever, but here’s a cheat sheet:

I’ve integrated all of my learnings and surprises into the individual sections below, but before we get there, one fascinating meta-learning that emerged from this research is how few levers individual companies found success in early-on. The median number of levers that the biggest marketplace companies relied on to kickstart supply growth was just TWO (and the average was 2.5). Though this isn’t necessarily true for everyone, the lesson here for most teams is to focus, focus, focus. Early on, you are more likely than not to find most of your success in a couple of levers. Figure out what those are and double down.

Now, let’s get into each lever (sorted by most commonly utilized):

1. Direct sales

One of the most significant learnings (and surprises) for me in doing this research was how important one-on-one direct sales was to most early marketplaces. Sales ended up being a crucial lever for about 60% of the companies I talked to — twice as common as the next biggest lever (piggy-backing and referrals).

Airbnb:

“Direct sales was critical to get the first listings on the platform, especially in immature markets without critical mass. It enabled us to pick and choose different supply types and build the right mix of homes. The local teams were accountable for their market and could themselves decide which supply to acquire, e.g. in which neighbourhood, what size of the listing, and price points.”

— Georg Bauser

OpenTable:

“On the restaurant side, unfortunately, there were no easy levers early days. It was hire a direct sales force on the street. People on the street knocking on doors, carrying the software. Demo’ing it and showing them how it worked.”

— Mike Xenakis

Etsy:

“The main thing that I believe really worked was recruiting sellers in person at craft fairs and elsewhere. This was a small activity in terms of human effort, but it scaled beyond that since the sellers marketed themselves.”

— Dan McKinley

Caviar:

“For us, for supply growth, it was direct sales / field sales - no question!”

— Gokul Rajaram

Uber:

“Uber Black was initially ops and phone driven. They would call limo companies to pitch them. A lot of limo companies were sole proprietorships, and the pitch was ‘While you are waiting for trips, we’ll guarantee you a minimum level of income if you keep this app on’.”

— Andrew Chen

DoorDash:

“The primary lever for restaurant growth was pounding the pavement, inside and outside sales, people on phones, door to door sales. The pitch is that we bring you incremental demand. Large QSRs and fast casual chains like McDonald’s, Chipotle, and Panera have quoted publicly that delivery is 70-80% incremental, and thus gives resturants access to new types of customers. We have always prided ourselves as being a merchant-first platform. For a small mom and pop business, they don't have many options to drive demand. They’re doing payroll, marketing, staffing; all of these things take them away from why they started a restaurant in the first place, and what makes them happy. We can do the marketing for you, and help keep your kitchen busy even when in-restaurant dining is slow.”

— Micah Moreau

AngelList:

“To grow initial supply, we asked a bunch of investors we knew to fill in a web form with their name, location, markets they like, investments per year, typical investment amount, etc.”

— Babak Nivi

2. Referrals

The second most common early supply-growth lever (tied with the next lever) was offering a referrals program — incentivizing existing supply to refer new supply. About a third of the marketplaces I spoke with saw a lot of success here.

Lyft:

“Referrals and ambassador programs were big for us early on. Double digits of %’s of new supply early on came from these programs. We went after students because our primary audience was younger and millennial. Some students made so much they had weekly lobster dinners. The pitch to students was to get some work experience and make some money. We had tiers of rewards -- the top tier was essentially a part-time job. As a reward at the top tier, we gave you a letter of recommendation from the COO of Lyft, which many students valued very highly, and was very cheap for us. Referrals (online program) was more impactful top-line, but Ambassadors (people referring users on the ground) were key piece to the launch strategy in each city -- seeding supply and demand ahead of launch. We were able to reduce overhead when launching a city this way, by getting the word out early.”

— Benjamin Lauzier

Uber:

“On the supply side, referrals was about 1/3 of the first trips — and they were also the best drivers. The other 1/3 was WOM, and 1/3 was paid.”

— Andrew Chen

Caviar:

“Referrals, yes, a big growth lever on supply in every market, both early in the life of a market, and later too.”

— Gokul Rajaram

DoorDash:

“Referrals is massive on the Dasher side. It is effective on the consumer side too but a lower % of our acquisition mix than dashers.”

Micah Moreau

3. Piggy-back off of an existing network (mostly Craigslist)

About a third of the marketplaces also relied heavily on piggy-backing off of an existing network (in almost every case, Craiglist) to bootstrap their supply growth. I don’t have a lot of quotes here (sorry!), but when it worked, it was the first or second most important lever for these companies.

Uber:

“The first thing the launcher team would do when they launched a market would do is figure out supply. They would go straight to Craigslist.”

— Andrew Chen

4. Word of mouth

Though not really a growth lever, organic word of mouth was a significant factor in the growth of early supply for about a fourth of today’s biggest marketplaces.

OpenTable:

“The restaurant industry is very tight. Every restaurateur sure knows each other -- so if someone is trying something out, there is a virality that takes place. We benefited from that. A year or two later, with the transient nature of restaurant employees, they are bouncing every couple of years -- if they go from one restaurant that’s using OpenTable, the first thing they say to the owner is that you have to get this software.”

— Mike Xenakis

Eventbrite:

“You can read our IPO filing — WOM was listed as a key strength and quantified as 36% of supply awareness.”

— Brian Rothenberg

Patreon:

“Creators come to the platform because they already follow their peers online, and thus see other creators launch on Patreon.”

— Tal Raviv

5. Subsidizing

Similarly, about a fourth of the marketplaces I spoke with bootstrapped supply by subsidizing (paying for it) in some form.

Uber:

“We used money to solve the problem. We’d guarantee you $40/hour to drive. All you had to do was maintain an acceptance rate of 70% and keep your app running. You could decline riders up to a point, but you don’t get paid for doing nothing.”

— Andrew Chen

Lyft:

“We had an income floor for drivers, to guarantee some amount of money per hour. This helped us jump-start the marketplace from scratch.”

— Benjamin Lauzier

Breather:

“You have to choose which side to subsidize. For Breather, that was the supply side. We subsidized it with things like furniture and locks, to increase the quality. With low size transactions (e.g. 2hrs), you can’t walk in and have it be schmucky.”

— Julien Smith

Zillow:

“We subsidized leads in almost all of our marketplaces to get them going. We wanted to show new users the quality of our connections and give them a risk-free way to get started. We would then slowly turn on pricing as we proved the value. This helped us build supply in the early days of each marketplace.”

— Nate Moch

6. Employees are the early supply

In a few cases (Rover, TaskRabbit, and DoorDash), the company’s own employees were the initial supply — both to create liquidity and to better understand the problem space.

Rover:

“All early supply was employees”

— David Rosenthal

DoorDash:

“We have a policy where everyone in the company dashes once a month. In the early days, there was always a shortage of dashers, so Tony and the team dashed constantly, close to every day. In addition, Tony and his wife had their weekly date night on Friday nights, and on some of those date nights Tony and his wife would dash together.”

— Micah Moreau

TaskRabbit:

“In the earliest days, Leah [the CEO] and the early team were Taskers. I remember distinctly dispatching employees from HQ when tasks would come in. In the early days, we were obsessed with ensuring that every customer who came to the platform had a delightful experience. If that meant we had to drop everything we were doing and run a task, we did. It was a great way to ensure quality in the early days.”

— Jamie Viggiano

7. Single-player mode

I was surprised to learn that the tactic of bootstrapping one side of a marketplace by offering that side a tool they find useful on its own (aka “single-player mode”) wasn’t more common. But when it worked (for OpenTable, Eventbrite, Patreon), it was the most important tactic for these marketplaces to get off the ground.

OpenTable:

“To get into the door with restaurants, we couldn’t lead by talking about online bookings -- there were no online bookings. We decided to invest in the software side of the business -- we created a solution that could stand on its own without the demand side. What this meant was building a suite of tools for restaurants to replace their manual booking process (usually a notebook they passed around). Our sales pitch initially was 90% “use our software to better run your restaurant”, and 10% “we’ll help customers find your restaurants and book a table online.”

— Mike Xenakis

Eventbrite:

“We made the product self-service for the supply side early on.”

— Tamara Mendelsohn

8. Performance Marketing

I was also surprised to learn how rarely performance marketing was used to grow initial supply, being a major lever early-on only for Lyft and Uber.

Lyft:

“SEM + Display + FB was effective early on for both supply and demand. It gave you a baseline for CAC that you can use for other levers. Even if it was a tinkle of growth, we had the machine going, and it allowed us to dial it up and down.”

— Benjamin Lauzier

Uber:

“The paid channel was half the signups, but only 1/3 of the first trips, which tells you it was the least efficient channel.”

— Andrew Chen

9. Loops

A couple of companies (Eventbrite and Airbnb) found a powerful supply-oriented loop (also known as a flywheel, or virality), which drove early supply

Eventbrite:

“We invested in strengthening viral loops in our product where attendees (the demand side) would become event creators (supply side). In addition, we had a free-to-paid loop where our free product (free to use for free events) attracted a lot of creators who tried the product for free first. Many of these free creators later hosted paid events, converting into paid users. The free viral loop ultimately drove 34% of supply-side awareness/acquisition, and 17% of creators who have produced a free event have gone on to host a paid event within twelve months (included in our public IPO filing).”

— Tamara Mendelsohn and Brian Rothenberg

Airbnb:

“Person books trip —> loves the experiance and gets an offer to make their home available for guests while on their trip to help pay for trip —> becomes host”

— Casey Winters

10. Events

And a few companies (Airbnb and Lyft) successfully organized events/meetups to help build early supply.

Airbnb:

“To launch a city, we’d travel there and hold a meetup. Here in San Francisco, it’s not a big deal to meet a founder. In other places, that’s pretty novel. They would get so excited that they met us that they’d tell their friends. The markets started turning on, and we religiously focused on making sure customers loved us.”

— Brian Chesky (source)

Lyft:

“An early part of our foundation was onboarding classes for drivers. We would bring bagels, and have dozens of driver applicants come at once to go through a series of educational videos & chats.”

— Benjamin Lauzier

11. SEO / Content Marketing

I was very surprised by how rarely SEO was impactful in driving early supply growth — only being a key lever for Eventbrite.

“We invested in blog posts, white papers, ‘How to Market Your Event’ articles that drove SEO traffic from creators.

In addition to content we wrote ourselves, we had a great UGC/SEO loop: 1) creators built their event pages with user generated content, 2) creators linked to their event pages on Eventbrite from their own websites, 3) these Eventbrite.com event pages ranked well in SEO. They also created content for and funneled link value to our "San Francisco events" SEO pages. 4) this drove both demand, and a good portion of supply as well.”

— Tamara Mendelsohn and Brian Rothenberg

12. Leverage your community

And finally, maybe the most unique lever of supply growth I came across in this research came from Etsy.

“One of the most effective early levers for supply growth was building the Etsy community, offline. After spending years going to craft fairs every weekend promoting the brand we launched a program called Etsy street teams that organized passionate community members around the country (eventually the world) and had them be on-the-ground brand evangelizers. We provided tools and money for these leaders to start their own “teams” (or chapters made up of other sellers) that went to craft/vintage fairs and promoted the Etsy brand to buyers. Some of these teams are still around and very much alive today. More recently Etsy has invested in traditional advertising but early on, they did nothing of the sort - it was sellers promoting their shops/the brand that drove growth. And they were not compensated -- they got value from sharing what they were passionate about, ie. Etsy!”

— Nickey Skarstad

Once you sense that you’ve got enough supply — or even prior to that (we’ll spend more time on how to understand this in a subsequent post) — you then need to figure out how to drive your initial demand. In our next post we’ll explore this exact question, covering the twelve most important early demand-growth levers across these seventeen companies. Can you guess what the first two most common growth levers might be? I was pretty surprised when I saw this. Hint: They aren’t performance marketing, SEO, referrals, sales, or PR.

Ask: If you work at any of the companies I looked into:

PLEASE let me know if I got anything wrong. I’ll correct it in the next post. Just reply to this email or DM me @lennysan.

If you have any other insights to share about what was important early-on for your company (or any marketplace company), I’d love love love to know. Please share!

Thanks for writing such detailed content Lenny. This shows that a few levers (1 or 2) can make all the difference for your business or probably anything in life.

Excellent content.