The ultimate guide to willingness-to-pay

How to effectively run your own WTP study, with templates, guides, examples, and more

👋 Hey, I’m Lenny and welcome to a 🔒 subscriber-only edition 🔒 of my weekly newsletter. Each week I tackle reader questions about building product, driving growth, and accelerating your career.

P.S. Don’t miss The Best of Lenny’s Newsletter book (all proceeds going to charity), Lennybot (an AI chatbot trained on my newsletter posts, podcast interviews, and more), my recruiting service (focusing on Sr. PM and VP roles), and my new swag store (great gifts for your favorite PM, or yourself!).

Q: How do I figure out how to price my product?

Pricing is the most under-leveraged growth lever. It can drive enormous sustained growth (quickly) and often takes very little product work, yet is rarely prioritized or even discussed within product teams. That’s because pricing can be scary, irrational, and hard to know if you’ve done it right. Yet everyone who invests in pricing wishes they’d done it a lot sooner.

Enter my friend Kristen Berman. Kristen is a behavioral scientist, a founder of Irrational Labs, and a past podcast guest and newsletter collaborator. For a decade, she’s worked closely with tech companies to drive behavior change. She leverages the latest behavioral-science research to improve products’ conversion, engagement, and, most impactfully, pricing. Just in the past few years, she’s helped dozens of companies revamp their pricing strategy—with tremendous results.

Below, based on her work and the latest research, Kristen shares the most in-depth and actionable guide I’ve come across on how to execute a pricing study (spoiler alert: there is way more than Van Westendorp). She also provides two mega qualitative and quantitative templates for you to use in your own pricing research. This advice is meaty and actionable, and will help any product leader on the hunt for new growth levers.

For more from Kristen, you can reach out to her here if you want to chat about pricing, watch her weekly teardowns on Substack, and subscribe to the Irrational Labs newsletter.

Pricing is one of the biggest levers to growth. Why are so few product teams testing their pricing?

At Irrational Labs, we surveyed 60 software companies to reflect on their experience with pricing studies. Of them, 50% said their companies have never run pricing studies, and only 25% reported even A/B testing a pricing change. Larger firms often have dedicated staff for pricing strategy yet are still generally reluctant to change the status quo.

Why do so few companies run pricing studies? Based on our work with dozens of top companies, we primarily hear:

It’s too risky. What if we annoy users? Reddit’s users flipped out. Strava had bumps. Patreon got blowback.

It’s technically complex. Testing multiple prices in the market for SaaS products also means maintaining them—which no technical team wants to do indefinitely.

Willingness-to-pay (WTP) studies are just hard to run. Recruiting participants, writing the study, and analyzing data requires lead time and some expertise. It can be intimidating.

These are legitimate reasons. However, the potential revenue gains from effective pricing often outweigh them. A McKinsey analysis suggests that a 1% improvement in your pricing can increase your profits by up to 11%.

So if you do decide to change your prices, how should you go about it? This article will decode the four most commonly used quantitative WTP methods and provide a template of questions you can use. Quant is very important, but it can be even more powerful paired with qualitative work. Likewise, we also included a robust qualitative research guide, focused on helping B2B companies with pricing. While the optimal recipe is to do both qual and quant, anything is better than doing nothing. As pricing expert Madhavan Ramanujam says on Lenny’s Podcast, “Talk to at least one person. Most companies are not even doing that.”

Willingness-to-pay methods: The rundown

The top four commonly used quantitative methods are:

Van Westendorp

Becker-DeGroot-Marschak

Multiple price list

Discrete choice or choice-based

Until recently, these methods were difficult to compare—the most frequently cited studies were published around 20 years ago. This changed in 2023, when Randy Gao, Simon Huang, and Minah Jung comprehensively reviewed the top methods, combining insights from dozens of papers to make sense of WTP. Their analysis builds on a compelling 2019 WTP field study and an in-depth comparison from 2011.

Below, I’ll run through the different methods and pros and cons. Every research method has trade-offs, and part of being able to trust your final results is understanding these nuances. At the end of the post, I’ll share six tips for implementing these surveys yourself, along with two mega templates to help guide you.

But first, a big disclaimer: Most of the below methods hold the product description constant while trying to determine some magical number that people will pay. But as pricing experts will tell you, this number, i.e. the price, is just part of the story. In reality, your product’s description and features, as well as what it’s compared to1, play a role in WTP.

Stories can add measurable value to seemingly worthless items. Someone paid $51 for this yellow bear figure. Why? The story makes it feel scarce.

Pasta that is described as “sauceable” commands an 80% higher price. Why? The adjective implies quality. If the marketing team asked customers, “What’s the most you’d pay for pasta?,” “sauceability” wouldn’t factor in—and the results would be off.

How much would you pay for a virtual whiteboard? Probably not $960 a year. Yet “the visual workspace for innovation” Miro charges $80 a month for a team of 10 people. Clearly, they’ve figured out positioning.

Assuming that price is a “magic number” implies that people have predetermined their willingness to pay for your product; they have a number in their head. But in reality, most of your customers haven’t thought much about it. They are deciding in real time what they’re willing to pay based on the information they have about the product. As a product manager, marketer, or designer, you decide what that information is. In other words, customers aren’t walking in with an unmovable POV—you shape their POV.

You have two levers to do this: (1) change your prices and (2) change your positioning. The latter starts long before customers reach your pricing page–but once they’re there, the impact of your copy, descriptions, and choice architecture on conversions can’t be overstated.

Let’s suppose you’re looking at changing prices and want to know what your customers are willing to pay. In that case, a quantitative pricing study is your best bet.

So what are the methods to determine WTP?

1. The Van Westendorp

If you’ve heard about pricing studies, you’ve likely heard of the Van Westendorp (VW) method (sometimes called price sensitivity meter, or PSM). But despite being the favored child in popular tech posts, it’s not a fully reputable method.

First, not many companies are actually using it. Of the 60 software companies we surveyed, only eight said they used it. And academics don’t use it either. The top VW study on Google Scholar has 36 citings (a low number) and was run on university students measuring their WTP for private dormitories. (Aren’t we through with using college students for psychology papers?) The other methods mentioned in this article have citings in the hundreds and thousands.

Perhaps most damningly, it was invented in the 1970s. Given the advancement of data science and research methods, surveys are not like fine wine—they don’t age well.

Why do people like it?

The pros: The method itself is pretty simple. You ask people four questions to find out the lowest and highest price they’re willing to pay for something:

At what price would it be so low that you would start to question this product’s quality?

At what price do you think this product is starting to be a bargain?

At what price does this product begin to seem expensive?

At what price is this product too expensive?

Participants typically respond to an open-ended question (empty text box). This is called the open-ended, or “direct,” approach in the literature. In this method, you’ll get what people want to pay instead of what they might pay.

The questions are straightforward—and there are only four. Win. And the continuous format, without a scale consisting of set intervals, gives detailed information on individual variation. This makes responses easy to analyze.

However, the Van Westendorp method has a big problem: the well-documented phenomenon known as hypothetical bias. Gao et al. sum up the issue in their recent paper: “Under hypothetical settings, people state a higher valuation than their actual valuations.”

What does this look like? John List, a University of Chicago professor and Walmart’s first chief economist, ran a donation study—the real treatment raised $310 for their cause, whereas more than twice that ($780) was pledged in the hypothetical.

We’re asking people to imagine a fake world and tell us what they would do in it. Sadly, we’re bad at predicting our future self’s actions. In a fake world, we have no competing priorities, we’re very rich, and we like lots of things2—not an ideal scenario for figuring out WTP.

Should you use the Van Westendorp? We say proceed with caution, unless you’re including questions that reduce hypothetical bias (see this guide for examples) and you’re focusing on more established product categories (versus products that are brand-new to the world).

2. The Becker-DeGroot-Marschak

To overcome the hypothetical bias associated with Van Westendorp, economists have developed “incentive-compatible” pricing methods. These methods give you an incentive to report what you would really pay (or rather, a disincentive for answering hastily or intentionally misreporting your willingness to pay). The goal is to more accurately gauge people’s true willingness to pay.

The Becker-DeGroot-Marschak (BDM) is arguably the most-used method in experimental economics. While it’s very similar to the Van Westendorp, it adds an important twist: it tries to eliminate cheap talk.

In the study’s original design, participants are asked to write down the maximum amount they’d pay for an item. Then a random number is selected. If the participant’s written amount is higher than this random number, they must purchase the item at the random number’s price. However, if their amount is lower, they cannot buy the item and they owe nothing.

This is important because, when answering, people think they may have to pay for the thing. There is skin in the game.

They don’t know the selling price in advance, so overstating might lead to paying more than their actual valuation—and understating might result in missing the opportunity to buy at a price they would have accepted.

This seemed to have removed most of the hypothetical bias3 that’s made the Van Westendorp method contentious. A semi-recent study looked at the sale of water filters to families in Ghana and found BDM had predictive power on demand, when compared with the straight sale of the filter.

Problem solved? Not quite. Critics point out that the method’s core mechanism, which involves a “random number” scheme for aligning incentives, is complicated. Be honest. Did you really understand how this worked from the above explanation? Many participants don’t either.

3. Multiple price list (or Gabor-Granger)

To recap: Becker-DeGroot-Marschak improved on the Van Westendorp method a little by “adding teeth” to the questions. But BDM can be hard to understand.

Another problem with the BDM method is that it asks people to name their price—to be price givers.

This assumes we have a predetermined number in our heads. It’s as if we expected our customers to always be thinking deeply about our product, just waiting for us to ask them how much they’d pay.

In reality, though, we’re price takers: we go to a website and it tells us the price.

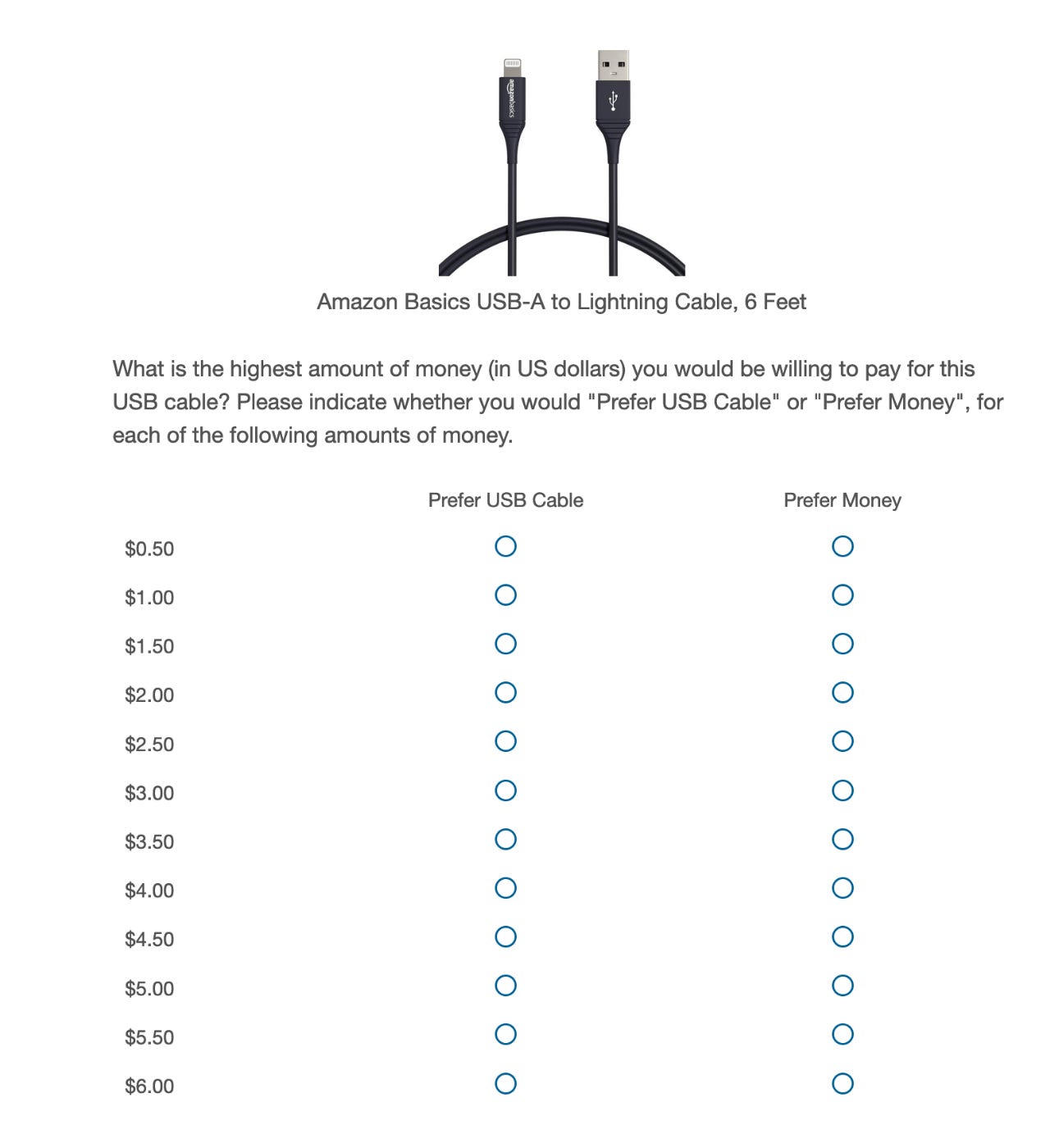

The multiple price list method (MPL) was developed to address this. In the BDM, respondents must state a maximum WTP (price giving). In MPL, on the other hand, the respondents must say yes or no to a list of prices (price taking).

Do you want to purchase this for $35? $45? $55? This lets you simplify the incentive-compatible element, because the researcher just tells the study participant: “One of your choices will be randomly selected and we will implement it. For instance, if you select $45 and you say yes to the $45 price point, you will have to buy it. If you say no to $45, you cannot buy it.”

So from an empirical perspective, is MPL better than BDM?

Historically, researchers have recommended MPL over BDM—mainly because it’s simpler and more transparent. This has led economists to use it widely.4

But new research points to some potential flaws. Gao et al.’s latest paper implies that the MPL method may mislead researchers to underestimate the value of their products. They run 10 experiments and show that the MPL method “actually leads to systematically lower WTP estimates.” This could lead researchers and marketers to underprice their products and leave money on the table.

Why? Possibly, getting people to pay attention to each value (yes/no) puts the focus on the opportunity cost of money—and this may decrease people’s willingness to spend it.

4. Discrete-choice-based

This last pricing survey method is fundamentally different. In the VW, BDM, and MPL methods, we ask people to decide about one product. In contrast, discrete choice involves giving people multiple product options with slightly different features and prices and asking them to pick one they would buy. Basically, you replicate whatever you intend to launch and describe it just as you would on your marketing page.

Silvia Frucci, a go-to-market leader at Optum, endorses this method:

“We used the choice-based pricing method at Optum. To figure out WTP for a new product, we asked questions along the lines of Which of the three products are you most inclined to purchase? The study asked this question five different times with a variation of feature and pricing combinations. Our sample was representative to our target; it went out to 12 provider practices via phone-based interviews.

The results had a really profound impact on our business. Based on this study, we found out the WTP for the product was lower than we assumed and adoption would be more difficult. Based on the survey insights, we ended up killing the full product that we were about to launch! Instead, we integrated the high-value parts into other existing businesses and products.”

John List also endorses the discrete choice method: “I would say when I cannot obtain revealed preference data, I would follow this approach to estimate marginal values.”

Why does he like it? It leverages relativity. We can’t assume that responses to a survey reflect absolute willingness to pay. But we can infer relative willingness to pay, and that comes closer to how we make real-world decisions: this or that?

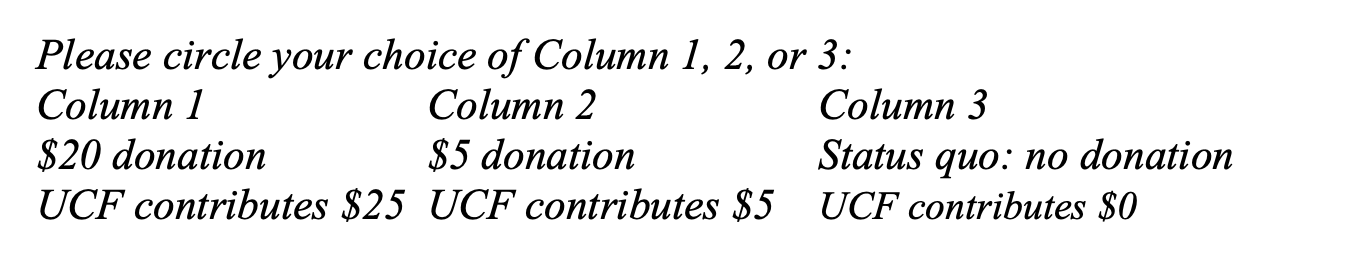

You can design it simply, with a couple of straightforward options:

Alternatively, you can ask the question six or seven different times and vary attributes. Here’s an example question using the discrete-choice-based experiment method for a random product:

Imagine you’re considering purchasing new and innovative enterprise software that can do the following:

Project management software that costs $8/month per user and can automate quarterly headcount planning

Project management software that costs $11/month per user and can automate quarterly headcount planning and provide what-if scenario planning

Project management software that costs $12/month per user and can provide what-if scenario planning and real-time headcount planning

Would not purchase

Please click around on the landing page and explore what these products can do. Then select the option that you would be most likely to purchase. At the end, we will choose 20% of the people who take this survey and sell them the product at the price they choose. Make sure to choose the product you would actually spend money on!

As with the other methods, we need to add incentive alignment to avoid cheap talk. In this method, it’s a bit easier. You can say a few people will be chosen at random to receive the option they choose.

If you’re familiar with conjoint analysis, you might rightly ask: Isn’t this just that? Yep. This is one type of conjoint. Qualtrics says it’s the simplest and most common. Full conjoints focus more on individual attribute trade-offs and ranking (which can be less “real world”), versus complete product choices. They also tend to be longer studies—which risks causing decision fatigue for participants. Maybe more damningly, they can be time-consuming to set up and hard to get right, and thus more expensive.

Discrete-choice-based studies are an art and a science. To avoid a long questionnaire, you’ll need to make some strategic choices on product bundles. And you need a statistical package you can use to analyze data. SurveyMonkey has strong examples of this on their blog (scroll down). Qualtrics (which Irrational Labs uses) has survey design packages. There’s also Conjointly.