Growth inflections

Stories behind growth unlocks for Figma, Facebook, Airbnb, YouTube, Tinder, DoorDash, and others

👋 Hey, I’m Lenny and welcome to a 🔒 subscriber-only edition 🔒 of my weekly newsletter. Each week I tackle reader questions about building product, driving growth, and working with humans.

Q: My product is growing, but slowly. I’m wondering if growth will ever take off. What have you found most often precedes an inflection in growth?

I love this question. Though I’ve written about how to kickstart a product’s growth, ways to boost growth, and what it feels like once you’ve found product-market fit, I’ve never looked into what precedes sudden inflections in growth.

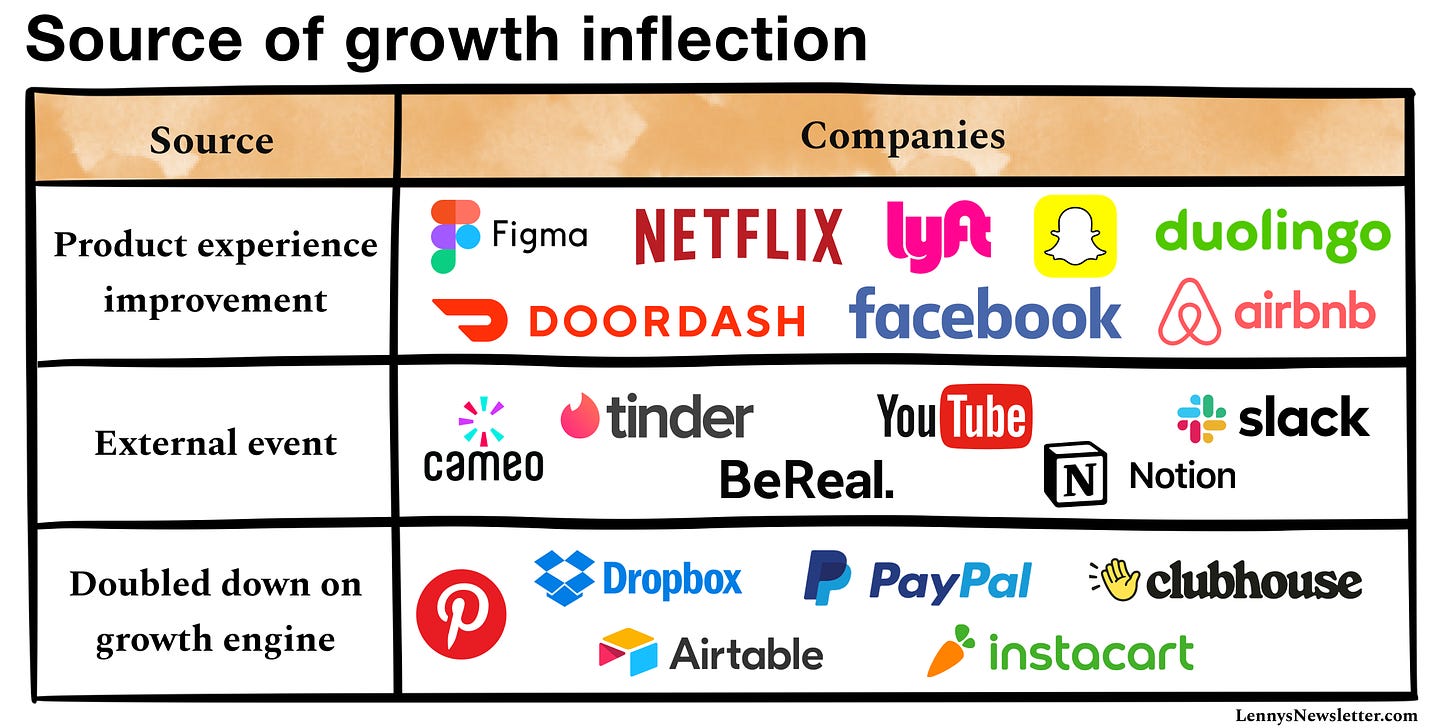

To find an answer, I spent the past couple of weeks researching inflection points for two dozen of today’s most successful products, and I found a few surprises:

The majority of growth inflections sprang from a product improvement

A surprising number of growth inflections came from an unexpected external event, without the product changing at all

Many of the most durable inflections came from the company leaning into their primary growth engine (e.g. SEO, virality)

Below, I’ll share stories of growth inflections from Figma, DoorDash, Tinder, YouTube, Snap, Airbnb, and many others. Here’s a quick overview:

It’s important to note that long-term sustainable growth is never as simple as just one thing. Although a single moment can (and often does) ignite growth, to build a durable business you’ll eventually need to get all three pieces right:

Ongoing product improvements, to build something people want/need

Ongoing events that get the word out

A well-oiled growth engine

But it often starts with a single moment. Let’s explore these stories.

Thank you, Badrul Farooqi (Figma), Cem Kansu (Duolingo), ChenLi Wang (Dropbox), Evan Goldin (Lyft), Jeff Chang (Pinterest), Jonathan Badeen (Tinder), Max Mullen (Instacart), Merci Grace (Slack), Micah Moreau (DoorDash), Lauryn Isford (Airtable), and Steve Chen (YouTube) for contributing to this post.

1. Product improvements

Though Andrew Chen popularized the Next Feature Fallacy—the mistaken belief that the next new feature will suddenly make people use your product—interestingly, the most common source of growth unlock appears to be adding that one additional feature. This doesn’t mean that you are one feature away from 🚀, but it does tell me that a better product experience is often at the heart of unlocking growth.

Figma (releasing team libraries)

“The biggest inflection began with the public release of Team Libraries in 2017 (about a year after launch). The sheer amount of leverage that it provided to design teams made Figma such an obvious winner against Sketch/Framer/etc. It changed the entire conversation with large teams.”

—Badrul Farooqi, first PM at Figma

Snap (launching ephemeral messaging, Stories, and face filters):

“Initially for Snap, the biggest growth accelerations consistently came from raw, pure, product-innovation-driven growth. Ephemeral messaging in 2011, Stories in 2013, and face filters in 2015—those drove our growth.

When IG copied Stories, it may have curtailed Snap’s growth in some international markets, and maybe with older demos where IG already had penetration, but it didn’t stop us. Snapchat was already dominant with younger users, in the West in particular.

There was also stuff like Bitmoji, Geofilters, Group Chats, etc., but those three above were the hits that everyone wanted to copy.

Later, growth was driven by much more traditional growth tactics, like performance, localization, notifications, and network expansion.”

—Anonymous early Snap employee

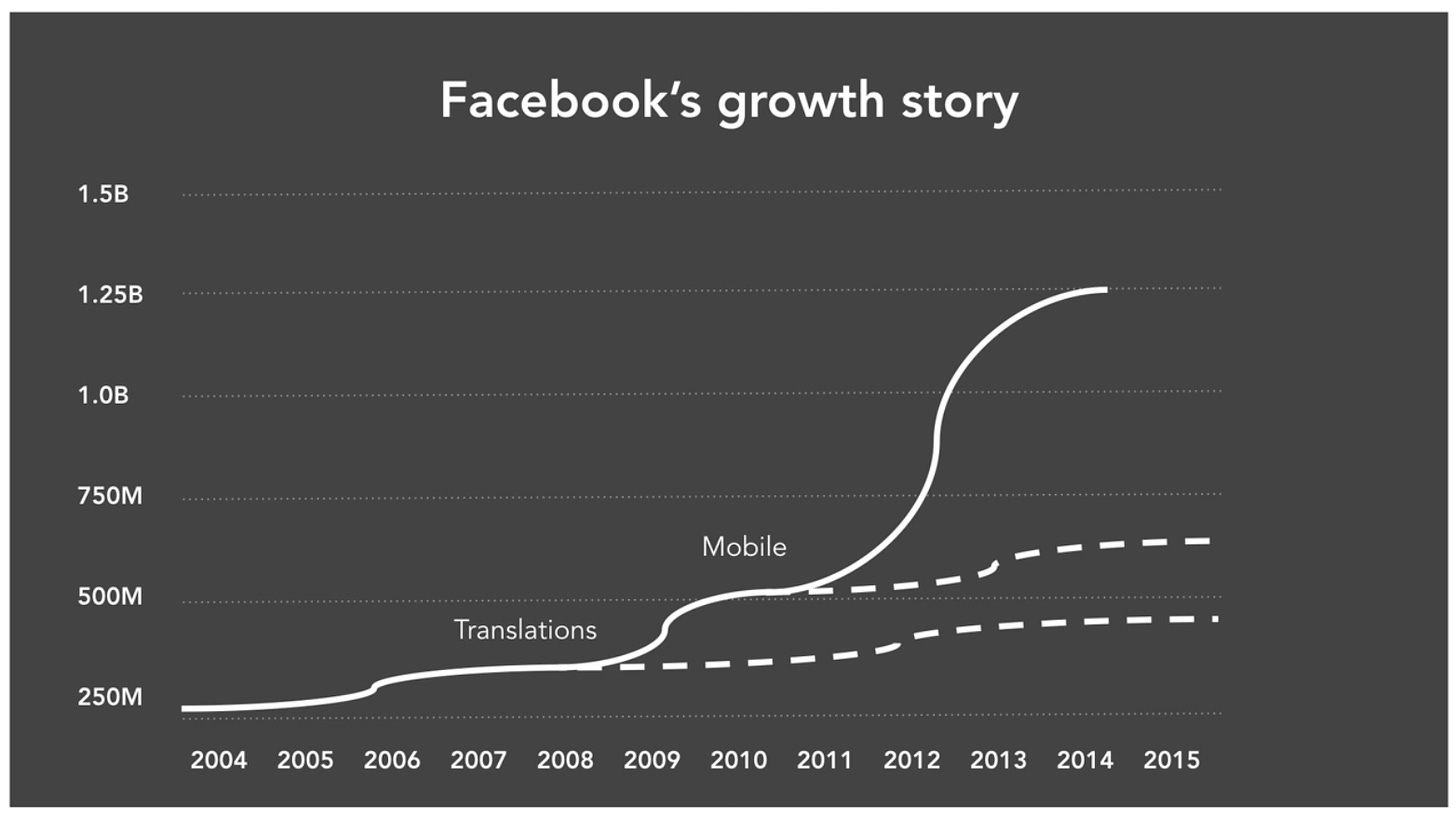

Facebook (adding translations, and then mobile)

“This is the timeline of Facebook from 2004 to 2015, their growth story.

Facebook had an excellent data science team, and they came to the conclusion that Facebook would be roughly 400 million users by 2015. Now we know that wasn’t really true, as they actually started growing really fast in 2008-2009. This actually was a result of something that the growth team came up with: translations. You want to make your product available for as many people in the world, and Facebook started hitting the limit on people who spoke English. They assumed that since the content was in the language while Facebook was in English that it would continue to scale, but that wasn’t the case. So they implemented this new platform that automatically translated Facebook into hundreds of languages, and the growth re-accelerated.

The same thing started to happen again in 2010-2011: mobile. The data science team was forecasting Facebook to be about 700 million users, or something like that, and because most of those people were using Facebook on computers, they hadn’t intended this massive shift that was happening in 2010-2011, which is people getting smartphones. Facebook had to switch entire teams to mobile—they even have large training classes for engineers who just are learning mobile. […]

The initial forecast of Facebook’s growth was about 400 million people, but Facebook today is an over-2-billion-user platform. If there’s anything we can learn from this, it’s that if you’re intentional about growth and you’re really trying to sort of break through these forecasts in these ceilings, you can grow really, really fast.”

—Gustaf Alstromer, YC Partner

Netflix (tweaking the combination of offerings)

“The original idea of Netflix didn’t work. But hundreds of failed experiments later, and after many a sleepless night of worrying, we finally tested the unlikely combination of ‘No due dates, no late fees’ and subscription that ultimately was the thing that ended up working. And boy, did it work. Within days of testing it, we knew we had a winner.

Where before we were struggling to get traffic, all of sudden we couldn’t keep up. Our previously prodigious amounts of inventory were suddenly not enough. Engagement soared, churn went dramatically down. Everything started working!

If there was a moment when Netflix stopped being a startup and became a real company, it was then.”

ーMarc Randolph, co-founder and first CEO

Tinder (launching their Android app—plus see part 2 below)

“We saw one of our biggest growth spikes when we launched our Android app. We knew there was pent-up demand for it, and we also knew we couldn’t really expand to markets outside of the U.S., U.K., and Australia without Android. This also coincided with localizing the app with translations. We didn’t really bother doing much international marketing and promotion until we had all of that in place. At the same time, we were so plagued by server issues and other issues that I was likely distracted and scared that we were going to lose it all.”

—Jonathan Badeen, co-founder

Duolingo (launching on mobile)

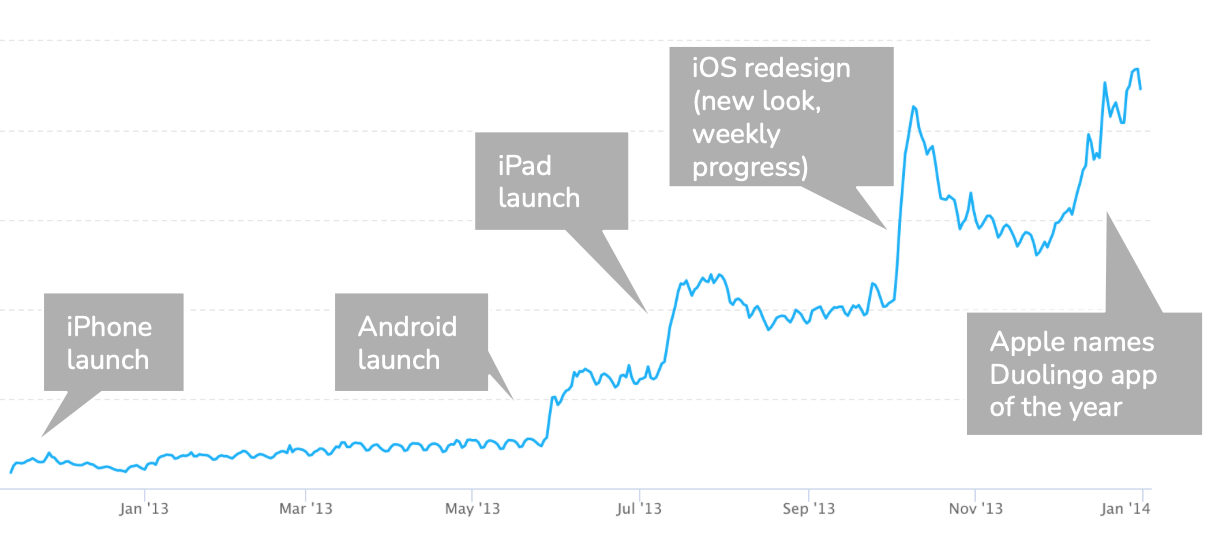

“The first big growth unlock for Duolingo was the launch of the mobile apps, and betting on mobile as our main platform. Duolingo originally launched as a website. In October 2012 we launched the iPhone app, and it quickly became the number-one downloaded app in the education category. We sent traffic from our website to fuel these downloads. We launched the Android app in May 2013, about seven months after the iPhone app launch. At the end of 2013, Apple chose Duolingo as the iPhone app of the year.”

—Cem Kansu, VP of Product

In marketplace businesses, the user product experience is tied directly to the quality and quantity of supply, and so, unsurprisingly, the biggest improvements, and thus inflections, in marketplace businesses usually come from improving supply:

Airbnb (expanding internationally and adding translations)

“No sooner had we learned to build supply than competition came knocking on our door in the form of a European copycat. (And when I say copycat, I mean it. We even found our job reqs on their site—some with Airbnb still listed as employer!) The competitor had just received $90 million in funding and ramped up to 400 employees in two months. Our guests use Airbnb to travel, and if we lost Europe, we really wouldn’t be in the business of travel anymore. Growing on our own timetable was officially out the window.

We needed to change tactics and go on an all-out blitz to capture as much of the European market as we could. First and foremost, that meant we had to be local. It was September 2011, and our site was woefully U.S.-centric. In just over three months, I purchased top-level domains for nine countries, assembled a global translation team, contracted with Akamai to reduce site load time, and restructured the UI on every front-facing interaction to support long text strings (crucial when you go from ‘average’ to ‘durchschnittliche’). We also shifted to a multi-currency payment platform.

Logistics in hand, it was time to build supply and demand. We’d already seen the value of having people on the ground, so we opened offices in eight European cities. [Co-founder and CEO] Brian [Chesky] cared about the types of people we hired, focusing on ‘missionaries’ and not ‘mercenaries.’ Emphasizing culture, we brought in employees who cared about and who wanted to grow the community. We also bought Accoleo and Crashpadder, two smaller players in Europe, to seed supply in Germany and the U.K. On the demand side, we had to think broader, with potential travelers coming from all over Europe. In January 2012, to officially launch in Europe, we did a PR blitz to drum up as much press as possible with campaigns like ‘Rent the country of Liechtenstein on Airbnb.’

This pace might sound too fast—and it was. The night before the international launch, we were still trying to get the homepage translated! And on the home front, we were undeniably neglecting operational challenges. But it was worth it. When competition comes after you, move ridiculously fast. Marketplaces are normally winner-take-all markets. If we had lost ground to European competitors in 2012, we may have never gotten it back.”

—Jonathan Golden, first PM